The revelation that a parliamentary researcher was arrested in March on suspicion of being a Chinese spy has sent Westminster “reeling” and left the British political establishment in “shock”. Or that, at least, is the impression offered by London’s news media, which has covered the scandal with barely contained excitement.

That China’s agents would dare to infiltrate the heart of the British government has been widely portrayed as an unprecedented development. “This is a major escalation by China,” one anonymous senior Whitehall source told The Times, which broke the news, adding that: “We have never seen anything like this before.” It is hard to know whether such sentiments are genuine or exaggerated for effect. Either way, they seem rather overwrought.

China has been engaged in extensive espionage operations in Britain, and around the world, for decades. As a 2021 report by the Intelligence and Security Committee stated accurately: “China almost certainly maintains the largest state intelligence apparatus in the world.” Moreover, as the report also noted, China employs a “whole-of-state” approach to espionage, co-opting a range of state and non-state actors, as well as ordinary citizens at home and abroad, to help carry out this work. Chinese students studying abroad, for example, may sometimes be pressured by the government into reporting information back to Beijing — though far more often about the activities of their fellow ethnic Chinese students than state secrets.

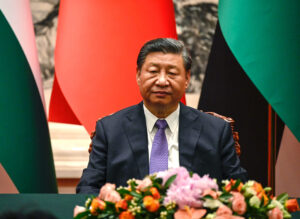

It is true that, in recent years, a rising China has escalated its overseas intelligence operations. Since he came to power in 2012, Xi Jinping has made what he calls “comprehensive national security” the central priority for China’s party-state. He has handed China’s premier foreign intelligence service, the Ministry of State Security (MSS), along with its military equivalents in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), greater authority and more resources both old and new (such as cyber) to more assertively collect intelligence, protect Chinese interests and project Chinese influence worldwide. The result has been the uncovering of a litany of hacks, thefts and scandals. Of these, the Chinese spy balloon that traversed the United States in February may have been the most high-profile, but was among the least successful and consequential (as compared with, say, MSS’s massive 2015 breach of US government security clearance records).

But this is simply what nation-states, and especially the world’s major powers, do. Though perhaps distasteful, it should hardly be a shock. In fact, Britain should be particularly familiar with the business, given its history as an epicentre of the Cold War spy game. Those who walk the corridors of power in Westminster and think the present situation is unprecedented had best read up on the Cambridge Five.

Of course, Britain and its allies in the Western world are also spying on China — as we taxpaying citizens might reasonably hope they would be, if China really is the security “challenge” our governments say it is. In July, CIA Director Bill Burns did not shy away from saying publicly that the agency had “made progress” in rebuilding and expanding its spy network in China, years after Chinese counter-intelligence managed to identify and kill nearly all of the CIA’s agents operating in the country, following a 2010 intelligence breach (potentially the work of either a mole or cracked encryption).

There is some evidence that our spies have been wildly successful of late — at living rent-free in Xi’s head, anyway. Because whatever the furore in London, it pales in comparison with the escalating level of paranoia about hidden hands and foreign forces that has emerged in Beijing in recent years. Not only is China in the middle of a sweeping ongoing counter-espionage campaign — with the MSS currently calling on the public to engage in a “whole of society mobilisation” to hunt down spies and traitors, and triumphantly highlighting arrests on its new social media account — but more serious, if mysterious, goings-on higher up hint that Xi’s concerns about the loyalty of his people could be playing havoc within the Chinese system.

The breaking news on Thursday night was that China’s defence minister, Li Shangfu, had been arrested and placed under investigation. The source for this information was, of course, US intelligence. But the fact had already been rumoured in China, as he had not been seen in public in weeks. Li’s fate seems linked to that of two top generals of the PLA Rocket Force (which oversees China’s nuclear weapons) who were hauled away a few months ago. The Force’s deputy commander, meanwhile, allegedly committed suicide. China’s short-lived foreign minister, Qin Gang, also suddenly disappeared and was replaced without explanation this summer.

There is no evidence, to be clear, that any of these officials were engaged in or suspected of espionage. The more likely explanation is old-fashioned corruption. The persistent rumour in China is that the PLA Rocket Force generals had taken money Xi handed them to expand China’s nuclear arsenal and pilfered it instead. Li, who previously ran the PLA’s equipment procurement department, may have been involved. But it seems plausible that the current atmosphere of extreme suspicion regarding foreign infiltration and subversion contributed to these officials’ exposure and removal, with Xi now no longer trusting the reliability of anyone, especially in his national security apparatus. Corruption itself can, after all, open the door to foreign intelligence services willing to wield blackmail or simply offer additional cash.

This distrust is particularly clear in Qin’s case. The ex-foreign minister disappeared after a Phoenix TV reporter strongly hinted that he’d had an extramarital affair (and fathered a secret child) with her while they were both previously stationed in Washington, DC. Since many Chinese officials have mistresses without facing any repercussions, and because Qin was previously considered personally favoured by Xi, some suspect that it was the fact that he’d engaged in his covert indiscretions only a few miles from Langley that was of greater concern. Naturally, the online rumour in China is that the TV reporter, Fu Xiaotian (who has also disappeared), was in fact herself an MSS agent deployed to Washington undercover.

Whatever the truth of these specific salacious cases, it is absolutely clear that Xi is quite convinced that the West and its agents are hell-bent on infiltrating China and subverting Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rule. Because Western countries “have always regarded China’s development and growth as a threat to Western values and institutions”, he thundered at an assembly of top party leaders in 2016, these countries “have not for a moment ceased their ideological infiltration of China”.

In this, he was merely echoing a long series of similar declarations, as in 2013, when he warned that said “hostile forces” were “doing their utmost to propagate so-called ‘universal values’” with an aim to “vie with us [on] the battlefields of people’s hearts”, split up China “overtly and covertly”, and ultimately “overthrow our socialist system”. For Xi, China is engaged in an “extraordinarily fierce” global ideological struggle with Western liberalism that, “although invisible, [is] a matter of life and death”.

Western leaders don’t necessarily disagree. President Joe Biden regularly describes the United States as engaged in a global “battle between democracy and autocracy”. Former President Donald Trump’s secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, went so far as to insist while in office that the United States must “engage and empower the Chinese people” to enact regime change, because, he asserted, “if the free world doesn’t change Communist China, Communist China will change us”. British Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, for his part, this week vowed not only to improve security but to “defend our democracy” — implying that undermining it must be Beijing’s actual target, rather than mundane intelligence gathering.

Both China and the West, therefore, not only suspect infiltration by the agents of their foreign competitors, but demonstrably view this as part of a much wider, more threatening, and more enduring struggle between rival systems. The hard truth, then, is that, in a very real sense, we’ve all been thrust back into an era much akin to the Cold War, when constant spying and attempted subversion were simply geopolitical facts of life. It may be best for leaders in Westminster, and indeed in capitals around the world, to come to terms with this not-so-unprecedented reality, and to move forward with open eyes: prepared, serious, and without naivety about what’s happening — but also without any undue shock and outrage. Surely the nation of James Bond, at least, can manage to carry on with good cheer.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/