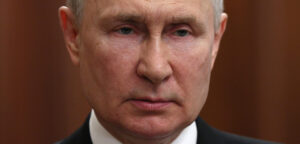

Waking up on Saturday morning, Putin must have wished he’d kept catering in-house. Only the day before, the Ukraine war seemed to be proceeding relatively well for Russia, at least by the lowered expectations of this stage in the conflict. The Ukrainian counteroffensive had made little progress in its first three weeks trying to breach Russia’s well-prepared defensive lines, and US officials were already briefing not to expect much more. The war had slipped into a tempo favourable to Russia, playing to the great strength of authoritarian systems against democracies: the ability to outlast the fickle whims and short patience of electorates and the politicians catering to them.

But the brief and spectacular rebellion of Putin’s caterer-in-chief-turned-condottiero, Yevgeny Prigozhin, seemed to suddenly upturn this calculus, highlighting the fragilities inherent in authoritarian regimes. Putin’s attempt to render Russia coup-proof by establishing multiple, rival power structures had created a striking weakness at the heart of his system. The great irony in all this was that the entire purpose of Prigozhin’s Wagner Group mercenary company was to firewall the Russian home front from the human cost of Putin’s foreign adventures, thus ensuring the stability of the regime. By the time Prigozhin’s disaffected warrior band was approaching the gates of Moscow, merrily shooting down the helicopters sent to delay their advance, the disadvantages of this approach appeared to far outweigh the benefits.

Early Western hopes, or fears, that Prigozhin’s escapade heralded either a Kremlin coup or a civil war did not quite capture the essential nature of the events. As the political scientist and civil war theorist, Stathis Kalyvas, observed, “What is going on in Russia is no military coup. Coups tend to be launched at the center seeking to generate cascades of compliance. This is an armed rebellion launched from a peripheral stronghold”, so that it is “hard to see how it could succeed short of mass defections in the Russian military”. But equally, “this is no simple mutiny either as those tend to be local and without broader political aims”. As the political scientist Seva Gunitsky observed on Twitter, “the closer parallel is not the [1991] coup but the Russian peasant rebellions of Razin and Pugachev. The latter especially — a disaffected officer unhappy with the prosecution of a war.”

Other comparisons, from war-torn and overstretched empires, could be made. The Albanian mercenary commander, Muhammad Ali Pasha, had an ability to outcompete Western rivals and reconquer restive provinces which made him indispensable to the Ottoman empire; Prigozhin has been similarly lavishly rewarded with lucrative monopolies. Prigozhin, just like Muhammad Ali, also used his independent power base to make a strike for the imperial capital, before turning back: and Prigozhin’s dramatic weekend adventure will similarly remain one of the great what-might-have-beens of history. If Putin’s reliance on deniable and expendable mercenary companies is a product of the postmodern way of war, then it had a curiously premodern outcome.

Prigozhin’s rebellion may have been brief, but its roots were longstanding. For months, the Wagner leader had utilised his newfound celebrity status to fiercely criticise the Russian Ministry of Defence’s lacklustre prosecution of the war. Accusing his main rivals, Russia’s Defence Minister “the Tuvan degenerate”, Sergei Shoigu, and Chief of General Staff, Valery Gerasimov, of poor leadership, cowardice, corruption and betrayal, Prigozhin had claimed that the Russian Ministry of Defence had deliberately starved Wagner of ammunition, emerging as one of Russia’s fiercest nationalist critics of the “fat cats in Moscow” in a surprisingly crowded field.

But the Wagner-led capture of Bakhmut, after a gruelling year-long campaign, seemed, until this weekend, to mark the apotheosis of Prigozhin’s career. Now it had achieved its purpose, at horrific cost, Wagner seemed set to be either redeployed to its lucrative African area of operations or neutered as an independent power structure. But as Wagner forces pulled out from their positions earlier this month, they fought clashes with Russian regulars they claimed had fired on them, capturing a senior officer. The tensions Putin had permitted to escalate within his war cabinet — whether as intentional policy or sheer incompetence must remain a matter of speculation — now looked to be spiralling out of control.

When the Russian Ministry of Defence published a decree two weeks ago that volunteer militias — like many official Russian statements, it did not mention Wagner by name — would soon come under its direct control, Prigozhin reacted with fury, refusing to come under Shoigu’s command, and again highlighting the incompetence of his new notional superior. In a half-hour Telegram video of unprecedented contempt last Friday, Prigozhin faced the camera with a mug of tea, calmly explaining to his audience — including Putin — that the war was launched under false pretences, purely to enrich oligarchs and boost Shoigu’s career, and that Putin had been catastrophically misled by his own military leadership.

Then came the purported shelling by the Russian army of Wagner’s positions behind the line in eastern Ukraine, where its mercenaries had been resting after the bloody and exhausting battle for Bakhmut. “Many of our guys died,” Prigozhin thundered on Telegram, “We will make a decision on how to respond to this evil. The next move is ours.”

And so it was. Announcing in an audio message that “the evil brought by the military leadership of the country must be stopped”, Prigozhin effectively declared war on Russia’s Ministry of Defence, while maintaining his personal loyalty to Putin: like any premodern rebel, the problem was simply that the Tsar had bad advisors. His forces would depose the military leadership before returning to the front lines: the war would continue, only better run. But first, “justice in the Army will be restored. And after this, justice for the whole of Russia.” In panicked-looking videos, the two generals seen as most sympathetic to Prigozhin, Surovikin and Alexeyev pleaded for him to turn back, to no avail.

Launching his self-declared March of Justice, columns of Prigozhin’s Wagner fighters crossed the border from Ukraine, and seized the southern military command headquarters in Rostov — the nerve centre of Russia’s war, deploying on the city streets in surreal scenes. There, Prigozhin released videos claiming to have evidence that Russian casualties were three to four times higher than the Ministry of Defence were announcing, and humiliating Russia’s now-captive Deputy Defence Minister General Yunus-bek Yevkurov, chiding him that “guys are dying because you’re throwing them into the meat-grinder, without ammunition, without thought, without any plans [because] you’re just senile clowns”.

Claiming to command a 25,000 strong force, Prigozhin then sent his columns striking north along the M4 highway, bypassing major population centres such as Voronezh in a “thunder run” towards Moscow, brushing aside the attack helicopters sent to slow their advance. As Putin gave a short and unconvincing speech, effectively likening himself to Nicholas II and threatening to crush the rebellion before seemingly fleeing the capital, lightly-armed internal security forces set up checkpoints on the city’s outskirts as Moscow residents received robocalls instructing them to support their liberators. The gambit was so successful, it seemed as if it must have been long-planned.

But the denouement, when it came, seemed anticlimactic: in negotiations reportedly overseen by Belarus’s strongman, Alexander Lukashenko, Prigozhin agreed to turn his forces back, and Moscow’s newly-erected defences were dismantled. Taking the applause of crowds in Rostov– in scenes which the Kremlin will have watched with alarm — Prigozhin went off to exile in Belarus and the immediate crisis had been averted. But what does it all mean?

The opaque and diffuse nature of power in Putin’s Kremlin means that it is impossible to make any assertions or predictions with any certainty: no one watching from the outside, tracking Prigozhin’s One Day That Shook The World on social media, knew what would happen next, and it is doubtful that any of the main participants themselves knew how the warlord’s daring gambit would end. But the speed with which Wagner forces approached the capital showed that the country’s internal defences, depleted by the deployment of the vast bulk of its army to the trenches of southern and eastern Ukraine, are strikingly weak. Rostov itself, the heavily militarised hub of Russia’s war in Ukraine, was surrendered without a shot fired. The lightly-armed Rosgvardia internal defence forces seen deploying around the approaches to Moscow were designed to protect Putin’s regime from political disorder, but they would have struggled to put up much of a defence against Wagner’s hardened troops and the heavy armour they were rushing to the capital.

After initial silence, Putin’s Chechen satrap, Ramzan Kadyrov, deployed a small convoy to Rostov to confront Wagner and flew troops to buttress Moscow’s defences: true to form, they achieved little, but the sight of auxiliaries from the imperial periphery summoned to the defence of the threatened metropole was a striking one, which may be repeated in Russia’s future. But apart from sporadic and largely ineffective aerial attack, the Wagner columns met no internal resistance: whether the security forces along their way felt outmatched, or whether middle-ranking officers felt sympathetic to Prigozhin’s campaign against their leadership, or simply chose to see who would emerge strongest before committing themselves, will now be an object of intense interest — within Russia as well as abroad.

Both Shoigu and Gerasimov have, at the time of writing, been notable for their absence. Speculation is rife that the condition for Prigozhin’s standing down Wagner was their replacement. Who replaces them, if this is indeed true, will affect the outcome of the war: but it is impossible to yet say to whose advantage. The events of Saturday’s rebellion were so unexpected, and so brief, that the Ukrainians were unable to exploit them to their advantage, at least immediately. But Ukraine’s leadership, and its Western backers, unnerved by the so-far disappointing results of their counteroffensive, will take heart that Putin’s hold on power appears so brittle.

The war is imposing huge human and financial costs on both countries, but in terms of political will, Ukraine now appears by far the stronger party. Wavering Western allies will surely assess that Putin’s near-escape from disaster this weekend will alter his strategic calculus, by showing that the war’s continuation threatens the stability of his rule in ways he had not anticipated. By showing that there are real costs to Putin’s seeming strategy of waiting out Ukraine’s Western backers, the weekend’s events will increase his desire to bring the war to a swift and palatable conclusion: that may make peace talks more likely, but it may also heighten the risk of nuclear escalation, already a discussion reaching fever pitch within the Russian security establishment. In determining which of the two outcomes is most likely, the opinion of China, surely alarmed by its partner’s sudden evidence of instability, will be a major deciding factor.

With Russia and China already rivals in Central Asia, Putin will not have been pleased by the noncommittal response to his moment of crisis from his former strategic dependent in Kazakhstan. Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s government only survived internal disorder through Putin’s intervention; the swift and painless execution of this mission once seemed to promise similar success in Kyiv. But already the junior partner in the alliance, reduced to a cheap source of mineral wealth for the hungry rising hegemon and a handy distraction for the West, Russia’s growing comparative weakness may alter the calculus of the strategic relationship, if not for Putin then for whoever eventually succeeds him: a permanent role as China’s Belarus is not what the war was intended to achieve.

In Belarus itself, for Lukashenko — if his role defusing the conflict does in fact reflect reality — the chance to demonstrate his utility to his Russian saviour may outweigh the inconvenience of hosting his volatile guest. But for Prigozhin, a precarious life in exile at the Minsk court of Putin’s puppet king is not an enticing prospect compared to the riches and glory that may still be attainable in Africa, if now under a tighter leash.

It is impossible to know whether Prigozhin’s weekend adventure will make him a major player in Russia’s future, or award him a death sentence: but if he wanted Putin’s attention, he certainly got it. One of the prime beneficiaries of Russia’s war in Ukraine, Prigozhin is also a fierce critic of the war’s prosecution and founding justifications. His critique of Russia’s sclerotic defence establishment, and its slow incapacity to react to events, was dramatically proved by his own actions. The former hot dog seller, previously accused of running backchannels to Ukraine’s intelligence services, is rightly vilified by the West for Wagner’s long list of human rights abuses, but he also must now look tempting as a means to pressure the Kremlin.

When, for all Prigozhin’s professions of loyalty, Putin condemned the rebellion as treason that would be firmly crushed, the Wagner leader did not back down, but continued on towards Moscow. Instead of a useful alternative power centre within Putin’s regime, Prigozhin now appeared an alternative power centre to it. This dramatic Saturday roadshow simultaneously humiliated Putin, and suddenly established Prigozhin’s own position — if only for a day — as the de facto second most powerful man in Russia. His survival will now depend on whether Putin finds the risks embodied in Prigozhin, greater than the potential rewards he promises if only given the opportunity to expand his role. The feared strongman looked weak and indecisive: his court’s once-useful servant had now thrust himself forward as the empire’s powerbroker. An increasingly frail-looking Putin has no obvious successor: looking weak and helpless, he was forced to watch the opening scenes of his succession crisis playing out while still alive. Western observers cheering on the fragility of Putin’s hold on power should be careful what they wish for.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/