When I first arrived in China in 1976, four years had passed since Nixon and Kissinger had gone to Beijing to meet Mao, kicking off what Nixon would label “the week that changed the world”. But that interval was not long enough to dispel the thick fog of misrepresentations and outright lies spun during that visit by both the Americans and Chinese — though none of those tales concerned what really mattered: the geopolitical victory that came from that trip.

At the time, exactly 50 years ago, the US was deeply divided by the Vietnam war. Congress was refusing to fund both that increasingly unpopular war and also the broad build-up needed to match the Soviet Union’s huge military upsurge. It would ruin the Soviet economy a decade later, but in the meantime, the US was being outmatched — until, that is, Nixon went to China and secured a diplomatic revolution that would open up a “second front” for the USSR. Among other diversions of Soviet energies, by 1976 at least 45 Soviet tank and motor rifle divisions were deployed towards Beijing, thousands of miles from Nato’s front in Germany.

Whatever else may be said against Nixon or Kissinger, their decision to open up to communist China at its worst — in 1972, the murderous cultural revolution was still in full swing — was a clever idea that many might have thought of only to dismiss it out of hand. All President Nixon had to do was embrace the malodorous Mao (his doctor would reveal that he never brushed his teeth, or bathed, unless he was in merry company).

But for Nixon the politician, the sacrifice was much greater, although he did not know it until the Watergate scandal drove him from office on August 9, 1974, two years after he had triumphantly landed in Beijing. The connection was straightforward: the centre-Right core of the Republic Party coincided with the “Taiwan Lobby”, which in turn encompassed the anti-Communist bloc, and which formed the hard core of Nixon’s supporters from the start of his political career. When Nixon betrayed the cause by embracing the very worst communist on the planet — altogether more extreme than the Soviets when it came to abolishing private property — and when he turned his back on Taiwan, the Republican Right did the same to him as he pleaded for help to fight off the Watergate charges.

A strange man in many ways — who else would think of himself as an absolute underdog while sitting in the White House’s Oval Office? — Nixon was also a real patriot: in 1942, assigned to the safest of Navy billets in Iowa, he strove very hard to manoeuvre himself into a combat zone. But had he known that his Beijing foray would leave him unprotected before his enemies and cost him the White House, he might have stayed well away from Mao.

Neither the American nor the Chinese media misrepresented that momentous strategic encounter, but they did join hands in utterly concealing the reality of China itself. For example, none of the admiring descriptions of Beijing and its imperial monuments in the New York Times prepared me for the stomach-turning stench that pervaded the city, and reached indoors as one tried to eat in the Beijing Hotel dining room. Throughout the city, human waste was not flushed away but carefully collected as precious “night soil” fertiliser, and then ladled into handcarts that were slowly pulled through the city to the surrounding vegetable fields.

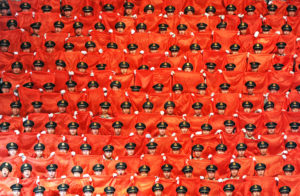

Nor did I read in 1972 about how the crowds in Beijing’s streets trudged from place to place in various states of clinical depression, understandably enough given the deep misery in which they were living — from their one-room-per-family, courtyard houses with no hot water to everyone’s shabby Mao suits and grey faces that evidenced border-line malnutrition. All this stood out even more because of the ubiquitous posters depicting ecstatically happy, rosy-cheeked enthusiasts applauding Mao.

Nor did anyone in 1972 care to mention that the officials they encountered — as I did four years later — were all suffering from intense sleep-deprivation: they had to reach their offices soon after dawn for lengthy pre-work “struggle sessions”, with the janitors and junior staff who run their ministry’s Revolutionary Committee playing Red Guards to upbraid them. The topsy-turvy rituals of the Cultural Revolution persisted until Mao died.

Instead of any criticism, the US press praised everything, including the health-giving virtues of riding a bicycle to and from work, even though Beijing’s summer air was full of faecal dust, with carbon monoxide added in the freezing winters of the coal-heated city.

A journalist of great fame at the time, James Reston, had already recounted his own marvellous experience of Beijing when he suddenly needed emergency surgery there in July 1971. His acute appendicitis could have killed him, but it turned out that the nearest hospital was fully equipped, and the surgery went well. It was only many years later, when Mao’s doctor defected and wrote his memoirs, that it emerged that Reston was taken to the hospital reserved for the top party leaders — the only one in Beijing fully equipped to treat him, or anybody who needed surgery.

The smell went away in later years as chemical fertilisers arrived, but many of the misrepresentations of that 1972 trip linger till this day — of which the most important by far is the legend of China’s strategic statecraft, superior by virtue of its very long-range perspective, then personified by Zhou Enlai. Because Kissinger negotiated primarily with Zhou, he elevated that servile toady — who never once tried to save life-long colleagues from Mao’s murderous intrigues — into a statesman of transcendental wisdom, fully endowed in the long-view department.

This was exemplified by Zhou’s answer to Kissinger’s fawning request for his retrospective view of the French Revolution. Indeed, Kissinger never tired of relaying the Great Man’s answer: “Too early to tell”. You see, you see, Kissinger would add, China’s greatest minds look ahead 200 years. Today, authors and publishers still use “playing the long game” in the subtitles of books about China.

They should not. Chas W. Freeman, the interpreter, immediately told Kissinger that Zhou was referring to the 1968 student uprising that overthrew De Gaulle, whose final outcome was indeed still unclear in 1972. But Kissinger refused to give up his two centuries for a mere four years, and continued to repeat the story when gracing the dinner tables of the extremely rich in subsequent decades. It was one of the simpler Kissinger mystifications: by turning Zhou into a great statesman, he qualified himself as one — unnecessarily, it would later transpire, because he had so little competition until Reagan arrived to deflate the balloon of Soviet power.

Kissinger’s lie about Zhou was only the tail of a much bigger rat: the historical falsification that ignores China’s stupendous record of strategic incompetence down the ages, in order to attribute profound strategic wisdom to the Han — a wisdom also embodied in China’s classic strategic manuals, with Sun Tzu’s the most famous.

To believe that legend, the most basic fact about Chinese history had to be ignored: again and again, after the downfall of the Tang — conventionally dated 618 to 907 — the Han were defeated, conquered and long-ruled by much less advanced invaders whom they hugely outnumbered. One can visualise how it went: a few steppe warriors in rags and furs would arrive, the Chinese generals in silks and shiny armour facing them would exchange oh-so-clever Sun Tzu citations, their army would be overrun, the country conquered, and then ruled for decades or centuries.

Over the thousand years down to the fall of the Jurchen-speaking Manchus in 1912, it was only during the Ming dynasty 1368–1644 that the Chinese were ruled by Chinese — very likely because the founder Zhu Yuanzhang started off as a monastery servant and could not have read Sun Tzu or any other of the delusional manuals that reduce warfare to clever tricks. Their uselessness was proved right into the 20th century, when the Japanese became the last of the badly outnumbered foreign conquerors to conquer Beijing, Nanjing, Shanghai, Canton and as much of China’s territory as they wanted, with both Communist and Kuomintang forces equally incapable of fighting them successfully.

At present no steppe warriors threaten Beijing, but the strategic incompetence of its rulers persists. Exactly at a time when the deeply divided United States needs allies to contain China, Beijing’s erratic aggressions since 2009 have overcome the neutralist preference of India (attacked in Ladakh and provoked over Arunachal state), the neutralist temptations of Japan (during the three-year ascendancy of the Democratic Party of Japan now extinct), the neutralist ambitions of Indonesia, and the pro-China tendency in the Philippines (just when many in the Philippines were inclined to slide into Beijing’s sphere, the Chinese responded by stealing islets and shoals).

Collectively, America’s new allies add enough mass to Vietnam and Australia — the first country to understand the China malady, in 2009 — to outnumber the Chinese, outweigh their economic achievements, and wholly overtake their less-than-stellar technological attainments. (Pentagon hyping of hypersonic FOBS missiles is shameless budget-pumping: they have no discernible purpose in the absence of ballistic-missile defences to underfly.)

As for quantum computing and artificial intelligence, only the severely ill-informed think that the Chinese are ahead. As late as 2020, Huawei’s boasts about its supposedly superior Kirin 980 microprocessors were widely believed; they even deceived poor Xi Jinping. Yes, they were indeed quite good but the technology was not Huawei’s — it belonged to the UK and US, which meant that Trump’s National Security Council could and did shut down Kirin production and much of Huawei’s as a whole with a couple of phone calls.

But Kissinger, who is still going strong, rated Chinese statecraft very highly when he published his China book in 2012. He believed, correctly, that the Chinese would continue to work hard, expand their economy and overtake slow US growth. He also thought, incorrectly, that Chinese leaders would transcend their zero-sum mentality, thereby allowing Washington and Beijing to arrange the affairs of a “G-2” world, in which — as he wrote — countries like India and Japan would have to find their places.

Always improbable, G-2 became impossible when Xi Jinping arrived. For him only G-1 is good enough. Not because he is a megalomaniac but the opposite: he thinks, accurately, that unless the Party establishes an unchallenged global hegemony, with its rule is deemed superior to democratic governance, Communist China will collapse just as Soviet rule did. He is right.

On September 9, 1976, while visiting a military unit near Beijing — I was the number-two in the delegation of J.R. Schlesinger, the just-fired Secretary of Defence — everything suddenly ground to a halt. Mao had just died. What followed was a series of bizarre events that would transform China forever.

First, there was the lying-in-state, in the shabby immensity of the Great Hall of the People in front of the imperial palace compound. The diplomats already in Beijing formed a long queue going up the steps — not in order of precedence, as is the custom, but in order of preference: Romania was then Number One because the Chinese had quarrelled with Albania while the “revisionist” Soviet Union was way in the back.

When we entered the hall where a very green Mao was lying dead, we saw that we were alone with China’s absolute rulers, “The Gang of Four”, were standing there: Jiang Qing Mao’s half-mad, super extremist, last wife; (he had long preferred sex with his very young “nurses”), Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan (two shabby Party bureaucrats), and Wang Hongwen (Shanghai’s tall, good-looking absolute boss, who had even transferred tanks from the border to strengthen his own huge workers’ militia).

He was the only one who greeted us with a nod while the others seemed… terrorised. They knew, as we did not, that they would be locked up very soon. Next, after I had made quite sure that Mao was dead, we were ushered into another room to mourn with the selected “best friends” of China: the North Vietnamese and North Korean ambassadors, with whom we could not speak given the absence of diplomatic relations, two Khmer Rouge envoys who looked like murderous dwarfs, and the Romanian ambassador who walked around saying what a really, really sad day it was, frantically trying to generate a minimum of civility between people determined to ignore each other.

Nor was I of any help: born in Romania’s Arad, I answered nu sunt sigur (“I am not sure”) to his “sad day” incantation. Utterly startled to hear me speak in his language, and totally embarrassed by my remark, he went to Schlesinger to be reassured that we were not all Romanians sent to catch him out.

I had left Beijing when the Gang of Four were arrested, but was back again when Deng Xiaoping announced that it was all over: the Cultural Revolution, the closure of China, Maoism. After that, it all went smoothly until the 2009 financial crisis when the Party bosses thought it was all over for democratic capitalism. Their reaction was perfectly predictable: since 2010, the PRC has behaved as if it were a cheap wind-up toy car, rolling straight ahead to collide with its neighbours, provoking increasingly adversarial reactions, and persisting regardless.

One example is enough for all: just when the Japanese government was sliding into neutralism, the PRC leadership turned a banal, drunken fishing-boat skipper episode just off the Senkakus (absurdly claimed by China) into an all-out attack on all things Japanese, from embassies and consulates that were besieged by hostile mobs to attacks against Japanese corporate offices, car dealerships, and even against individual Japanese — all provoked by incessant calls for revenge from hysterical officials. The final outcome was the election of Abe Shinzo’s LDP, which squarely took on China as an adversary.

Meanwhile, the US elite, both with Nixon at the start and then after Deng Xiaoping’s opening of China’s economy, was more than content to preside over the de-industrialisation of the United States, uncaring of the ultimate political consequences of replacing many millions of $30 per hour factory jobs with $10 an hour “service economy” jobs, with the incoming flood of cheap consumer goods supposedly alleviating the impoverishment.

Now, of course, China presses against all its neighbours, endowing the United States with new alliances, some overt and official, others overt but without any formal treaty, and others emerging — a process destined to continue until Xi Jinping, who, with his talk of “war readiness”, is now in his Mussolini phase, triggers an armed affray serious enough to stop the arrival of tankers and bulk carriers into Chinese ports.

When that happens, malnutrition will not be far behind, because of China’s critical dependence on imported animal feed. In 1976, rice, sorghum, cabbage and rare slivers of chicken were enough. Not today. If Xi Jinping falls, pork prices could be the cause.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com