The future of the Christian religion in England is not to be found in the southern shires or the former mill towns of the North. Out there, the voice and tenor of the Bible is a thinning force, a hoarse whisper. In London, the most multicultural part of Europe, it is closer to a deafening roar.

Consider British GQ’s next cover star, the Ealing-born Bukayo Saka. The 20-year-old English footballer has had a redemptive story since he missed the losing penalty in the Euros 2020 final last summer; he has been the brightest star in a rejuvenated Arsenal team that has a good chance of getting into the top four in the Premier League.

Along with a snazzy photo shoot, Saka recorded a video for GQ in which he lists his ten most essential items. There is an iPad, a portable music speaker, some Twix chocolate bars, a football, a PlayStation, trainers, and moisturiser: all the things you’d expect any sporty young man to be proud of possessing.

But Saka also included something else — a Bible, gifted to him by his father. “Religion is a big part of my life,” Saka says in the video. “Obviously I’m a strong believer in God.” Of course, by religion Saka means Christianity. And the use of obviously is striking: why is it obvious he would be a strong believer in God as a young person born and bred in the capital city of a western European nation? Well, it is obvious to him because of his family. Saka comes from a Nigerian family. And for many black African communities in Britain, Christianity is everything.

So Saka, one of the standard-bearers of the England national football team — which substitutes for religion in the country at large — also embodies another fascinating nexus: the relationship between a black British identity and Christianity, a religion that was introduced to anglophone west Africa by the British.

There’s a concept called the pizza effect. The original pizza was once a basic dish found in different pockets of Italy: a flat bread spread with tomato sauce; no toppings. When immigrants from Sicily and southern Italy moved to America between the late 19th and early 20th century, they introduced pizza to Americans. And these Italian-Americans, on the streets of New York and Philadelphia and Chicago, gave this basic dish a renewed colour: it became a food of multiple toppings and textures. After the First World War, pizza was reintroduced to Italy. And it became pizza: not just a flat baked bread with some tomato sauce — but a national dish of magnificent variation.

The same is true of Christianity in Britain today.

Christianity is collapsing throughout Britain. A British Social Attitudes Survey from 2018 concluded that this decline is “one of the most important trends in postwar history”. More than half of the British public now say they do not belong to any religion, compared to 31% in 1983. But there are parts of the country where the flame of the religion is still bright.

You have to go to London, especially the inner-city, to find England’s most vigorous forms of Christianity. It is largely West African immigrants who fill the pews of decaying churches from Peckham to Woolwich, who renovate new churches in Brixton and Lewisham, and who volunteer for Christian centres and charities up and down the capital. If you want a solid sense of the sacred, a connection to Britain’s ancient Christian past, you are more likely to find it while eating jollof rice in a big tent in Kennington than eating a Yorkshire pudding in a small room in Harrogate.

This is not a utopian vision of liberal multiculturalism. London is the most cosmopolitan city in Britain. We all know that. But it’s also the most religious and socially conservative city in the country. 62% of Londoners, for instance, identify as religious, compared with 53% of the rest of the country. 25% of Londoners attend a religious service at least once a month; only 10% of people outside London do. 24% of Londoners think sex before marriage is wrong, compared to 13% of the population. London is the most homophobic city in the country: 29% of people in London think homosexuality is wrong, while 23% outside London think this.

The city is not only diverse in markers of visual difference, such as skin colour and types of dress, but also in values. There is social libertinism and social conservatism and everything squeezed in-between. Many tend to focus on diversity in terms of surfaces, rather than diversity of values. The awkward tensions of the latter are tacitly accepted, like a squeaky-clean parent knowing his kids spent the night doing drugs in their bedroom but not mentioning it at breakfast the next morning. It’s a very British sort of relationship — traversing that thin border between tolerance and hypocrisy.

In the city 56% of Christians pray regularly. Only 32% outside of it do. London is more Christian today than it was during Margaret Thatcher’s time as Prime Minister. According to David Goodhew, the director of ministerial practice at Cranmer Hall in Durham University, between 1979 and 2012 there was a 50% rise in the number of churches in the capital city. Many of them are built in boroughs of London with a large black population such as Southwark.

The political scientist Eric Kaufmann points out that secularisation is “almost entirely a white British phenomenon”. When the share of white British people decreases in an area, secularisation also slows down. The number of white British people who ticked no religion in the census rose from 15.4% in 2001 to 28% in 2011. By contrast, the number of black Africans who ticked no religion in that same time span rose only by a tiny amount: from 2.3% to 2.9%.

Given it’s black Africans who are driving the rise of Christianity in London, conservatives who want to renew Christianity in Britain would do best to stop relying on public pronouncements by Justin Welby and Pope Francis. Instead, they should lobby for an open-borders immigration policy for all the African countries Britain once colonised.

Many of these communities are Christians because of the British Empire. Christian missionaries may have been a part of colonialism, but their influence extended beyond the colonial government, establishing schools and discouraging practices hitherto common in pre-colonial Nigeria — human sacrifice, slavery, twin infanticide, and polygamy.

Christian missionary schools also provided the foundation for many forms of African nationalism. Pro-independence leaders, like Obafemi Awolowo and Nnamdi Azikiwe, were educated at schools established by missionaries. Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, an icon of revolutionary black African nationalism and the first leader of a black African country to gain independence from a European colonial power, was educated at a Catholic missionary school.

Meanwhile, Yoruba Christians have incorporated the God of the Old and New Testament into their own language. Whenever Yoruba people pray, for instance, they use the word Olódùmarè to refer to the God of the Bible, and this is the same name for the God of the native Yoruba religion.

It’s unsurprising, then, that many black Africans in Britain today emphasise the importance of Christianity to their identity. In general, black British people are more than twice as likely to say religion is very important to them. Most black British believers are Christian. Yet the centrality of Christianity to black British identity is hardly spoken about. Saka treasures his music record and his football. But on Instagram, his name is not Bukayo Saka but “God’s Child”.

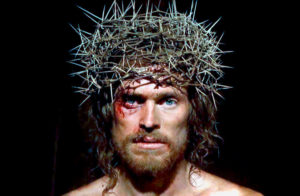

Christianity can accommodate tension. It is both radical and conservative: it proclaims the downtrodden will inherit the earth and it praises life-long monogamy. It incorporates the puritanical fervour of Leviticus and the ravishing sensuality of the Song of Solomon. Its central figure is both a man who was abused and spat on and crucified, like a slave, but also a figure of transcendent divinity. What can be more beautifully Christian than the fact its future in the bosom of what was once the largest empire in the world is now being sustained by communities it once colonised?

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com