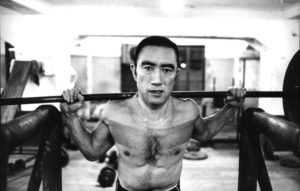

What’s the point of physical exercise? What’s the purpose of heaving, puffing and snorting your way around a gym three or four times a week? Personal health, obviously. The opportunity for competition at a demanding level of physical engagement too. But in a culture obsessed with appearance, exercise is increasingly seen as little more than a route to aesthetic perfection — a perfection designed not even for self-satisfaction, but to be deployed in competition with other aesthetically-perfect individuals.

It’s a tendency that no fitness company has reflected better than CrossFit. Once a branded fitness regimen combining different gymnastic and strength-training disciplines into a competitive community of leaderboards and point-scoring, the company has crystallised into a cult-like movement.

As someone with a lifelong interest in fitness, I was ripe for grooming and initiation, and duly became a dedicated member. And proselytiser, too: I helped expand the Panther CrossFit affiliate at the University of Pittsburgh in 2008 and practised the CrossFit methodology for three years. While many criticise the programme — for its links to supposedly Right-leaning first responders, its internal issues with sexual harassment, or past controversial remarks by its former CEO concerning the BLM movement — these issues never bothered me during my years of practice; the entire fitness world leans Right. No, the simultaneous appeal and sickness of CrossFit lies deeper, beyond the headline controversies, reflecting an undying hunger for a slickly-marketed blend of fitness, community, and competition. It’s an obsessive, dogmatic programme that I ultimately couldn’t handle.

CrossFit has achieved one feat that many thought impossible: it motivated a multitude of women to embrace heavy lifting. Even though many often demonstrated unsafe or improper form, it persuaded both genders to experiment with Olympic lifts, deadlifts and squats. It highlighted the value of plyometrics, kettlebells, and standard circuit training. As strength coach Mark Rippetoe — himself a critic of CrossFit — aptly stated; “Since the invention of the equipment a hundred years ago, nothing has placed more hands on more barbells than CrossFit.”

However, a crucial distinction arises when one looks more carefully into CrossFit’s methodology. The programme, with its emphasis on “Workout of the Day” and techniques introduced in their certifications, can be categorised as exercise rather than training. At a fundamental level, exercise denotes physical activity undertaken for immediate outcomes, often limited to the workout session’s duration. In stark contrast, training is an orchestrated endeavour, meticulously designed for long-term goals. While training maps a well-planned route towards a future objective, CrossFit’s randomness, typified by time-bound, randomised, and often high-intensity sessions, fits snugly into the exercise bracket.

This scattered approach reflects a deeper issue with the programme which goes well beyond exercise praxis. When executed diligently, the CrossFit inductee’s life begins to revolve around CrossFit. Suddenly, their social media brims with CrossFit-centric images, their routines become unyieldingly anchored to its workouts, and to question the ordained methodology becomes borderline blasphemous. A poignant instance came when a friend experienced a catastrophic injury in a car crash due to not wearing a seatbelt. CrossFit, to its credit, produced a video highlighting his predicament to raise funds for his medical needs. Yet, it seemed almost reflexive for some in the video to attribute his survival to his CrossFit-honed fitness, overlooking the undeniable importance of basic safety measures.

Such an approach is symptomatic of CrossFit’s sales technique, of how it appeals to a world desperate to look good. It positions itself as a unique sanctuary, an oasis of elite fitness in an otherwise out-of-shape, indifferent, normie world. The plethora of CrossFit documentaries and the seemingly ceaseless surge in CrossFit-centric social media postings reveal an insular, almost narcissistic universe. Sure, showcasing routines in minimal attire may garner “likes” and comments — perhaps even “sponsorships” and a little money (always less than one thinks). But beyond the digital applause lies an unsettling truth. The exercises might not be groundbreaking, but they are elevated to an undeserved pedestal by a community reluctant to explore beyond and a company ultimately motivated by one thing.

As a business model, CrossFit resembles a pyramid scheme, with enthusiasts splurging on costly monthly affiliate memberships in the hopes of ascending to the elusive apex. The irony is stark: many top CrossFit athletes likely spend more than they earn, often on performance-enhancing drugs. The world of competitive CrossFit has experienced its fair share of doping scandals, with men and women constantly searching for loopholes in a system perennially playing catch-up. And the nature of the allegiance to CrossFit becomes evident when the workouts, which are ostensibly random, are treated as gospel, exactly the kind of reverence that leads to injuries.

The more enlightened trainees soon realise that there isn’t a singular path to fitness. CrossFit’s branding as “the sport of fitness” is almost cyclical: you train using CrossFit to excel at CrossFit. Unlike, say, baseball, where exercises enhance specific skills like pitching or running, CrossFit lacks a distinct endgame. The CrossFit Games are mere amplifications of standard routines, chosen for spectacle rather than substance. In an age dominated by digital personas, CrossFit provides an enticing avenue for social media optimisation, not physical contentment. It relies on constantly stimulating a demand for perpetual improvement, a demand born of perpetual feelings of inadequacy. It’s the process by which an interest can become an isolating dogma.

Two decades ago, Robert Putnam offered a prescient diagnosis of this sense of atomisation in his book Bowling Alone. He observed that while more Americans in the late-20th century were bowling, they were increasingly doing so not in leagues or teams, but on their own. Though most easily observed in sports clubs, it’s a tendency across Western societies, from Masonic lodges to trade unions. The associative networks we used to practise leisure in have been swept away by the tide of hyper-individualisation that has rushed across all of civic life.

CrossFit has updated and exacerbated this to a terrifying degree. In a world where community ties continue to fray, it creates a semblance of togetherness (at a hefty price) while actively pitting its participants against each other. Beneath all the surface camaraderie and personal pride lies a more solitary reality. This isn’t akin to community sports leagues of yesteryears, woven with continuity and local legends. It’s a dog-eat-dog competition to climb a rope, thrust a barbell into the air, and then row on a rowing machine rather than the open water. Not for achieving personal bests but for social media clout in the relentless race to determine who looks coolest while exercising.

Unfortunately, there’s no singular path to holistic health — not raw eggs, raw meat, SoulCycle, CrossFit, or any other smartly-marketed fad coming down the line in 2023. As we navigate the maze of modern fitness, here’s a golden opportunity to remember that diversifying our approach to health might not only protect us from injuries but also from the empty echo chambers that modern fitness cults, like CrossFit, can all too easily become. The world of fitness is vast, filled with myriad effective ways to train and grow. But it shouldn’t become a route to better social media posts, or reduced to a game that, years in, you forget why you started to play.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/