Redding, the capital of Shasta County in the far north of California, spreads out in thin strips of suburbia, its freeways reaching up into mountainous upcountry. Here, 19th-century gold-mining settlements crouch in the valleys among snow-ridged glaciers and lines of pine trees ravaged by the yearly forest fires. Looming over all of this is Mount Shasta, a huge volcano associated with Native American legends, New Age cults, and purported UFO sightings.

Shasta County has always attracted American outliers, a laboratory for both success and failure. These are the valleys and mountains where John Steinbeck sent his characters in Of Mice and Men and The Grapes of Wrath, escaping from the restrictive cities and scarce land of the Midwest. In the Seventies, hippies fled the fading counterculture of the Bay to live communally here. Today’s exiles take the form of a conservative militia.

When the Covid pandemic hit in March 2020, California’s Democratic governor Gavin Newsom enacted America’s first state-wide stay-at-home order, before introducing some of the country’s strictest measures, closing schools and mandating the wearing of masks in public buildings. The health officials in Shasta, aware of local sentiment, attempted to limit the extent of these policies and consequently implemented some of the most lenient lockdowns in the state. However, if the fiercely independent residents of Shasta bit their tongues and did as they were told, it was grudgingly, and only up to a point. According to many libertarians in Shasta, lockdown measures threatened their livelihoods, while vaccine mandates were viewed as a further infringement on their personal liberties. So, when Shasta County’s elected Republican Board of Supervisors suggested residents take up their grievances with state legislators, enraged residents took matters into their own hands.

Over the past three years, the established local political elite — a wealthy class of Reagan Republicans that has traditionally run the county from its ranches and legal offices — has slowly found itself recalled and replaced with libertarian newcomers. Post-Covid, only Mary Rickert, a local cattle rancher who describes herself as an “incredibly conservative Catholic” (though others in the town label her a “rhino” — Republican in name only), remains in office.

Patrick Jones, whose family owns a local gun store, helped to overturn the once mighty Republican majority by convening a new movement made up of libertarians, evangelical conservatives, the local Cottonwood militia, the Shasta-based Liberty Committee, and anti-California secessionists. Jones and his three other newly elected insurgent supervisors — Kevin Crye, Chris Kelstrom and Tim Garman — are backed by Right-wing millionaire Reverge Anselmo and Mike Lindell, a leading Trump associate. And now that lockdown is over, this militant faction has even bigger targets: their goal is to return Shasta to traditional ballot-box voting, to abolish what some consider to be California’s unconstitutional gun laws, and to secede from Sacramento and become part of a new breakaway State of Jefferson.

High on mutinous ambition, residents of Shasta County (population: 182,139) find themselves at the confluence of several distinct American forces, each with its unique worldview and a disregard for ideological enemies. There is little consensus to be found beyond a shared sense of American crisis. There is also fierce resistance from Rickert and her equally odd coalition of progressives, liberals, moderates, conservatives, public worker unions and local media outlets; the rare Democrats and liberals who reside this far outside the Bay Area have to work closely with Republicans.

Yet no matter what side of the conflict they occupy, the people here are keen to describe how the state of California has abandoned its rural peripheries, exporting state-wide problems around drug abuse, homelessness, farming, land use, water access, forest fires and property prices.

Another element to consider, whose presence is felt everywhere in Redding, is the powerful Bethel Church, led by pastor Bill Johnson; it espouses an overtly political theology and counts many local politicians among its flock. Almost everyone I stayed with was a member of this megachurch, which espouses an extreme form of Pentecostalism. One host, with a beard of biblical proportions, prayed over me in tongues while a taxi driver offered to cast out my demons. Yet when I asked about the church, people often went silent, perhaps fearful of the last time they were dragged into the media. In 2019, members of the church — which practises grave-soaking, whereby the energy of deceased Christian leaders is “sucked” from tombs — attempted to resurrect a dead toddler. Since then, however, Bethel’s influence has continued to grow: its music division still racks up millions of views on YouTube. And yet, Bethel was the only organisation in Shasta to decline my request for an interview.

I arrive in Redding by train after dark and look for somewhere to see out the night, but the station’s main building is locked up and surrounded by a large spiked fence. A torch flicks on, and a security guard asks where I’m heading and where I’m from. He tells me the station was closed because of homelessness: “They shit everywhere and ruin the place. They’re coming up from San Francisco and LA, or they’re being sent… Who knows?” Instead, I find a bench beneath a poster warning against fentanyl use.

The next day, I walk to my hotel across town and amble past a roadside rally of MAGA flags, libertarian regalia, and what look like old Tea Party signs from the 2010s. A huge truck blasts its horn in support as it speeds down the freeway. An old man standing behind a stall filled with Trump leaflets gives me a nod as families and individuals stop to talk.

Later, I join the open session of the local Board of Supervisors, which, in 2020, was the focus of tense protests and debate over lockdowns. The hall slowly fills up; the majority are retired hippies or conservative ranchers from out of town. What starts as a regular local government meeting dealing with the prosaic business of water reservoirs and local art foundations quickly escalates into a debate about Trump, Covid and voting fraud.

Speakers from the floor discuss the pros and cons of Dominion voting machines, whose manufacturer was recently paid $787.5 million by Fox Corp to settle a defamation case involving cable news pundits and conspiracy theories. The conversation soon spirals out into stolen elections, national corruption, drug addiction and the “lies” of the media class. One local stands up and claims she had seen buses run by the San Francisco government dropping scores of homeless people in Redding at night. Another man in a trucker hat points to the serried ranks of local journalists and shouts: “I’m watching you. You don’t intimidate us anymore.” Yet the tenor of today’s political debate is comparatively anodyne; three years ago, amid lockdown controversy, one constituent told the board that “you have made bullets expensive — but, luckily for you, ropes are reusable”.

Although the recall efforts have a large civic element, they have also been bolstered by the Cottonwood Militia, one of several active groups across California. It was started by local barber Woody Clendenen in his barn back in 2008 and counts around 1,000 local business owners and ranchers among its ranks. Indeed, Cottonwood Militia members often intersect with other organisations such as “the Jefferson Movement”, “Red, White and Blueprint” and local evangelical churches.

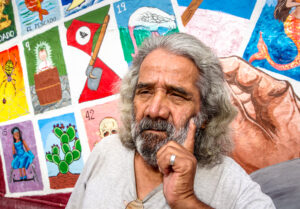

“They’re different legs of the same spider,” Carlos Zapata, a Cottonwood militia member and restaurant owner tells me over a drink in the local saloon of the nearby town of Palo Cedro. For Carlos Zapata, the militia “is here with a message that we’re not going anywhere…we’re here to fight [government overreach]. We want to take this project into rural America and the nation in general.” Zapata, like many others in Shasta, was drawn to the militia during the pandemic. He tells me: “Covid was like this Great Awakening. People started showing up to protest in droves — they wanted to join something because they thought we were going to civil war against the opposition. Do we need a civil war? I’d hate to think we’d need a civil war, but how do we get past this?”

“I had heard about a militia my whole adult life in Shasta,” says Doni Chamberlain, a local reporter. “And I kind of thought: ‘It’s just a bunch of guys out in the woods with paintball guns.’ I had no idea until George Floyd’s death. During the 2020 riots in Portland, there were all these crazy stories about Antifa coming down with truckloads of bricks. We had a protest here in Shasta. That was the militia’s coming-out party in Redding. There were more militia members than there were protesters. There was a mix of open and closed carry guns.”

“They’re faux-cowboys,” she says. “Most of them, I would say, are from average California towns. I think they’ve just embraced the whole gun culture because they believe that a civil war is coming — us against them.” She later describes how one resident told her that she “should be publicly executed… that the only way people like me learn is to be dragged behind a car”. And yet, she argues that many people in the county are acting in good faith, even if they are fundamentally misguided: “I understand there are some people who joined the militia for what they thought were good, valid reasons. What’s more American — or manly — than protecting your city from riots?”

A few days later, I meet Patrick Jones at the family shop, Jones’s Fort. (“Come to my gun store,” he says, “you’re English — you probably don’t get to see many.”) The shop is a large building on the edge of town where the heads of elk and bison hang beside the racks of rifles and shotguns. In a back room adorned with two massive buffalo heads, he leans up against a chair in a pair of old cowboy boots.

“I’ve been in local politics a while,” he tells me, “but when I won my [Board of Supervisors] primary in 2020, that’s when a lot of the excitement started. I’m a traditional, small-state conservative”, emphasising that his political vision is regional rather than federal. Indeed, much of what he and others argue is in step not with contemporary protectionist Trumpism, but with the earlier Tea Party movement. During the 2010s, the Tea Party was concerned with fiscal conservatism, national debt reduction, lower taxes and a small state. “This area is conservative, and it should have a government that reflects that,” Jones continues. “We rose up and did something about it. It’s our job to push back.”

Indeed, Jones has long been associated with the State of Jefferson (SoJ), a movement that opposes the cultural and political dominance of Sacramento, Los Angeles and San Francisco. The SoJ is a group with roots in the 19th century when the remote north became a natural resources hub for the cities. By 1941, SoJ activists had set up armed roadblocks around Northern California and Southern Oregon, unilaterally declaring succession before the Second World War interrupted.

Jones maintains that a break from California and the creation of the SoJ — from the northernmost counties of California and parts of neighbouring Oregon — will take an uprising. “There have been hundreds of attempts to split the state. But there’s no way, legally, for us to break away,” he says. “The only real way, if it’s ever going to happen, is for the people here to rise up and make it happen. Rural parts of California have no representation today. So splitting the state would allow us to form a more conservative government where you are paying less tax and are more free. We’re setting a trend. We have five counties in California watching what we’re doing here right now.”

Leaving Jones, I head to the Shasta County office to talk to Supervisor Mary Rickert. I’m joined by her husband Jim. Both are long-time cattle ranchers whose families have farmed in Shasta County for five generations. Neither believes that a libertarian SoJ would solve any of Shasta’s problems. “Some 85% of our funding comes from state and federal dollars,” Rickert says. “We’re a taker, not a giver. We couldn’t survive.”

However, she shares Jones’s distrust of Sacramento’s ability to effectively govern Northern California. “Gavin Newsom is not agriculture-friendly,” she says, giving a stark example. Under Californian law, she can’t shoot the wolves that threaten her cattle. “But why is a wolf’s life more valuable than a cow’s?” She maintains this isn’t really a priority for the militia. “I’ll be very clear, I believe they’re using Shasta County to elevate themselves. To his followers, Jones talks about not working with the government,” Rickert argues. “But behind the scenes, he’s for his personal gain through government grants to promote a new gun range.”

Before I leave Redding, I call Mark Baird, the leader of the SoJ movement. When he picks up the phone, the line is hazy; he’s under the wing of a small aeroplane in remote Siskiyou County, where he works as an aerial firefighter.

Baird identifies two flashpoints in Northern California history. The first is the 19th-century discovery of gold, which transformed the region into a resource hub with less settled urban populations than the powerful South. For Baird, second in importance are the constitutional reforms of liberal Republican governor Earl Warren during the Fifties that reduced rural representation at the state level. “We have a model in California, where the northern third of California has six state-level representatives and the other two-thirds has 114,” Baird tells me. “As you can see, the natural resource counties, and the rural counties, never win. We never get anything we want [and then] all of this lunatic bullshit comes up from Sacramento. The State of Jefferson is really about ‘Rule of Law and Liberty.’ As Thomas Paine said in his funny little pamphlet, oddly enough called Common Sense, all parts of the colony need to remain representative.”

For Baird, state and national politics, across all parties, have fundamentally betrayed these principles and grown distant from their voters. “It’s time for the people to take back the government that they formed to represent them,” he tells me. “They’re not doing anything for anybody — except lining someone’s pocket and I guarantee you that someone lives in Sacramento.”

In some sense, America has always looked back to its early leaders for political prototypes. At the national level, the current arena seems to be dominated by a contest between Biden’s technocratic and institutionally focused Hamiltonianism and the plutocratic Jacksonian populism of Trump. On the open frontier, however, far from centralised power, a third model appears to be re-emerging: that of Jeffersonian yeoman democracy. Whether this very American brand of folk libertarianism will survive a 2024 national election year remains to be seen — especially if the race becomes defined, as seems likely, by the need for an economically interventionist policy in the face of mounting competition with China.

Despite all this, many in Shasta County seem determined to mount political resistance against a changing world. Much like the cowboys of old, they’ve barricaded the saloon, and they’re waiting, guns drawn, for a showdown at dawn. From this distance, however, it’s hard to tell whether the pistols and hats are even real.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/