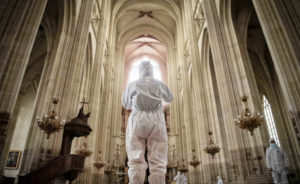

In the summer of 2020, protestors — and criminals — installed a reign of disorder in many American cities. On the news and on social media, one could see videos of arson in Minneapolis, mass looting in Manhattan and Los Angeles, blocked highways in Texas, and protests in Washington, DC, in which crowds of activists harassed and intimidated restaurant patrons. These actions, though alarming to many Americans, were met with nuanced sympathy and outright endorsement in venues of polite liberal opinion such as the New York Times, the Nation, and National Public Radio.

Watching the mainstream accept, or even welcome, such incivility, in defiance of public health directives that had banned even the smallest of public gatherings, was a dizzying experience. After months in which Americans had been cajoled and sometimes ordered into staying isolated and indoors, the script had suddenly changed.

It changed yet again after January 6, 2021, when “riot” no longer meant an eloquent expression of the “language of the unheard”, something to be championed or at least sympathetically understood, but a despicable betrayal of the nation, akin to treason or terrorism. For the establishment, norms around civility seemed to matter only as a weapon against the Right.

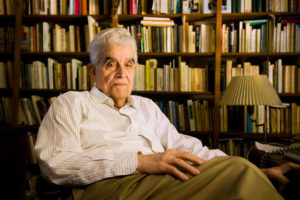

For the political scientist Alex Zamalin, however, the problem with America is simply that there is too much civility. A self-defeating desire for moderation and compromise at the expense of radical-Left politics, he argues in Against Civility: The Hidden Racism in America’s Obsession with Civility, is “everywhere you look”.

According to Zamalin, “a consensus narrative” has emerged in American elite political discourse. While he avers that without civility, our “everyday life” would be impossible, he argues that “politics is not everyday life” — it is a distinct “arena of power and struggle”. And our obsession with finding “common ground” with opponents and preserving “nonpolitical” spaces in our society is holding back anti-racist movements.

Zamalin is certainly right that politics shouldn’t be everyday life. Preserving the political character of politics — that is, making sure that it remains an enclosed arena of competition over power — is as necessary as protecting everything outside that arena from politics’ crushing intensity. We might describe civility, rightly understood, as the formula that lets us keep politics in its proper place — as an intense but limited contest among rivals who see each other as belonging to the same community.

For Zamalin, however, civility is a central theme of American history, and it has always been an arm of white supremacy. In its historical sections, Against Civility offer a wearingly familiar story that pits villainous white racists and misguided black moderates like Booker T. Washington against virtuous radicals like W.E.B. Dubois and Malcom X.

In Zamalin’s telling, the failures of America’s black radicals are inevitably the result of their having adopted “white” standards of civility. When Martin Luther King, Jr. excluded the gay writer James Baldwin from the 1963 March on Washington, the civil rights leader was, Zamalin argues, “applying the same standards of civility found in the white racism he denounced”. Two decades later, when Baldwin, in a public conversation with Audre Lorde at Hampshire College, declared that he couldn’t understand why Lorde, a lesbian feminist, insisted that black women faced struggles distinct from those of black men, he too was replicating the moral failures of whites.

It is hard to understand why prejudice against gay men or resistance to feminism among black intellectuals should require explanation in terms of white people’s moral failings, or what this has to do with civility. Unless, of course, one shares Zamalin’s implicit premise, common across a swath of the American Left, that only white people possess real moral agency. When black people err, it is through a kind of excursion into, or infection by, whiteness. Indeed, white people appear in this conception as the authentic protagonists of history, which they drive forward by their nefarious will to dominate.

The role of non-whites, by contrast, is to offer romantic but ultimately ineffective resistance. Every generation’s valiant struggles for justice are suppressed by open enemies and unreliable allies who insist on upholding civility rather than seeking racial equality. That this narrative might be insulting, given that repeatedly trying the same thing and failing is a sign of political ineptitude, doesn’t seem to compute.

Zamalin appears equally dense about recent history. In his account, the years since Trump’s election in 2016 saw elite moderates punish those who bravely spoke out against racism, such as former NFL player Colin Kaepernick. In fact, Kaepernick’s activism was lionised by the mainstream media — GQ magazine named him “Citizen of the Year” in 2017 — and led Nike to offer the ex-quarterback a multimillion dollar sponsorship and his own branded clothing line. Likewise, while the Black Lives Matter movement might seem to have imposed its slogans throughout many of America’s prestige institutions, Zamalin can only see it as a force at the margins of society, “dismissed” and “treated with disdain” by elites.

It is certainly true that BLM has not managed to effect meaningful changes to American law enforcement, except insofar as violent protests and riots in the summer of 2020 lead many municipal governments to constrain the policing of sensitive neighbourhoods, causing a spike in crime that has led to hundreds more murders than might otherwise have taken place. But while it has been unable to achieve substantive legislative changes, BLM has been taken into the bosom of American elites, neutralising the movement’s radical potential while draping the country’s institutions in the moral authority of anti-racism.

Zamalin cannot seem to comprehend the double-sided nature of the contemporary politics of anti-racism. As an ethical discourse, it is hegemonic throughout US universities, corporations, offices of government, and even the military. At the same time, it appears totally impotent as a political force. Making sense of this would mean sounding the strange gulf between discourse and power in our era. It would mean, for example, asking how Donald Trump — who, as Zamalin recognises, flamboyantly transgressed norms of civility — managed to violate all the political pieties of the conservative establishment only to fail to achieve any of his goals once in office.

For the nationalist and anti-establishment Right, Trump’s orgy of incivility was the beginning not of its empowerment but of a detour into spectacle, in which the imaginary pleasures of “owning the libs” and annoying the media took precedence over winning actual political victories. The January 6 “insurrection” was the ultimate drama in this theatre of resistance. Clueless conspiracy theorists stormed the Capitol on Trump’s behalf, as if, once freed from the shadowy forces holding him back, he might finally accomplish his stated goals.

No sensible person on the Left should wish such a fate for their own side. Or rather, sensible people on the Left might grieve that their own side has for years been caught up in the same fantasies of uncivil resistance, and the same unmooring from the realities of power, that now characterise the populist Right.

In the 21st century, the dramaturgies of protest against the Iraq War led by groups like Code Pink were as elaborate as they were ineffective. These protests were the template for the Left’s resistance to Trump a decade later — both were noisy, lame, and brought Nancy Pelosi to power as Speaker of the House.

Incivility of this sort is dangerous precisely because it is impotent. Theatrical gestures like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s appearance at the Met Gala in a “Tax the Rich” dress and Trump’s mockery of journalists share with the BLM riots and January 6 a common perversion of the difference between politics and everyday life. Performative incivility disrupts our normal, non-political lives with attention-seeking dramatics while at the same time draining politics of its specificity and substance.

What we need is not more incivility — more self-aggrandising antinomianism by narcissists posing as radicals — but a painstaking recommitment to a kind of civility that, by keeping politics off the streets, out of schools, and out of our private lives, channels it back into contests over policy.

If we want real change, from the Right or the Left, we need to depoliticise everyday life and repoliticise politics. If we do not, we will remain stuck together in an unbounded arena of shrill, but pointless, symbolic struggle.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com