A few days ago, I took a stroll to the shops. It was a glorious morning and the parks and cafés were full of families enjoying the sunshine.

Perhaps the shops were a little quieter than they would have been a year ago; but they were busy enough.

The restaurants were preparing for lunch; the mood was relaxed and happy. And nobody — yes, nobody — was wearing a mask.

That, of course, is the giveaway.

I wasn’t in Britain but in Sweden, a nation which stood alone in Europe in refusing to institute lockdown.

And as I queued to buy my son an ice cream, I was struck by the contrast with the situation back home. Like most people, I never imagined that the lockdown would last so long, or that the consequences would be so calamitous.

A taste of freedom: Swedes have been free to soak up the sun, play sports and socialise during the pandemic

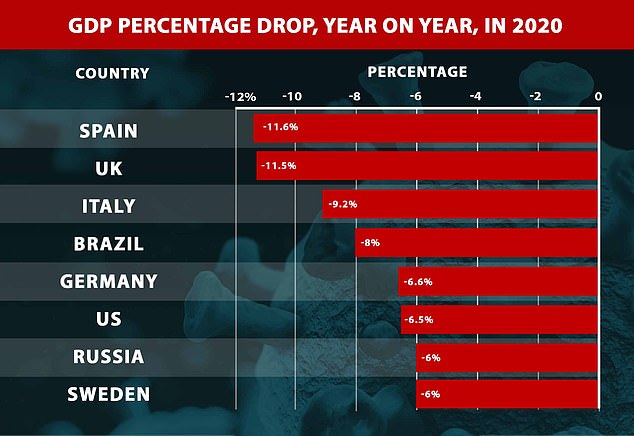

A strict three-month long lockdown in the UK is expected to see the economy contract by around 11.5 per cent in 2020

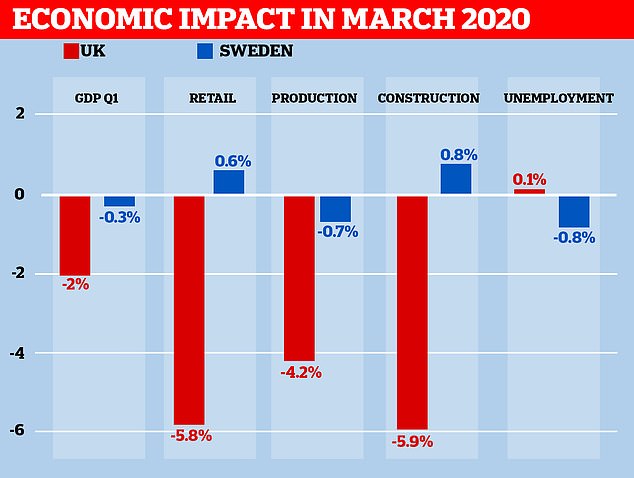

This graph shows how the UK’s economy has already been ravaged by the pandemic, with sharp falls in GDP, retail sales, industrial production and construction work – even when the latest figures include only a brief period of lockdown. The UK’s unemployment rate increased only slightly in the latest figures, but separate statistics show a nearly 70 per cent rise in the number of people claiming Universal Credit

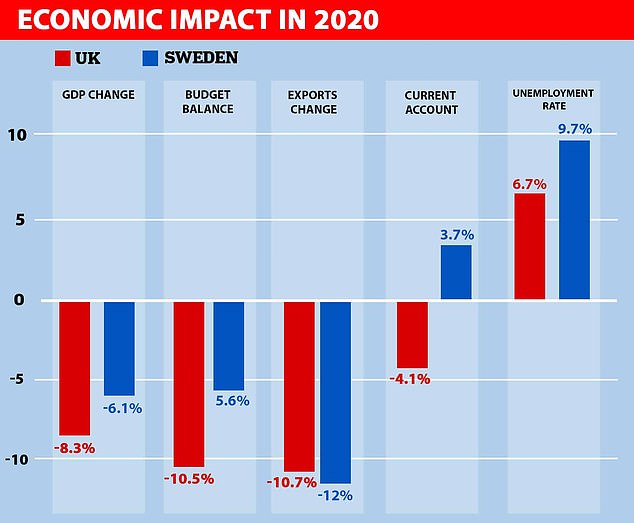

This chart shows forecasts for the rest of 2020, with the UK’s GDP set to plunge by more than Sweden’s – while Britain is left with a larger budget deficit because of the cost of propping up the economy. Britain will also have a deficit in the current account, which is related to trade – showing the flow of goods, services and money between countries. However, the EU expects Sweden to have a higher unemployment rate this year

Indeed, a few weeks after Boris Johnson announced the draconian restrictions on lives and livelihoods, I wrote on these pages that fears of a second Great Depression were overblown, and that with the right spirit, Britain would quickly bounce back.

But as the months went by and we sank into inertia, my optimism evaporated.

Recent figures suggest that our economy shrank by 20 per cent in the first three months of lockdown, a far worse decline than in other industrial countries such as the U.S. and Germany.

Most experts believe the worst is yet to come, with the Bank of England predicting that unemployment will hit 2.5 million by the end of the year. And even that may be too optimistic.

Yet despite these dire projections and the need to get the nation up and running — and in spite of the good news on the dramatic fall in death rates and admissions to hospital — parts of Britain remain in the grip of near-terminal paralysis.

City centres are deserted, commuter trains empty and the offices that are open operating with skeleton staff. As a result, countless shops, pubs, restaurants and cafes have not bothered to reopen — and may never do so.

As for Boris Johnson, he appeared to have vanished without a trace — at least until the Mail tracked him down to a remote Scottish location this week.

The Government seems incapable of giving a lead and the public mood is characterised by bickering and bitter negativity. There is little sign of the upbeat, can-do spirit we badly need to revive our national fortunes.

Sweden had a long-established plan for a pandemic and was going to stick to it. Pictured, people play beach volleyball at Gardet park amid the coronavirus outbreak in April

So it was with a sense of relief that two weeks ago I boarded the plane to the Swedish capital Stockholm. For in Sweden, leaders kept shops and offices open throughout, insisted that children went to school and still do not tell their citizens to wear masks.

Yet I can’t deny I felt a twinge of anxiety. As fervent admirers of all things Scandinavian, we’d arranged our family holiday when the coronavirus was merely a glint in the eye of a Chinese bat. Occasionally I wondered if we might be sensible to cancel it. But my wife, a much braver person than me, would not hear of it.

And quite apart from the attractions of cinnamon buns, unspoiled forests and glittering Baltic waters, I was curious to see how the Swedes were getting on.

For months their country has been the great outlier, inspiring admiration and horror in equal measure.

Some reports claimed that ordinary life was unchanged. Others, especially in Left-wing circles, attacked Sweden as a dystopian disaster zone, as if the streets were littered with unburied bodies.

The author of the country’s coronavirus strategy, a mild-mannered state epidemiologist called Anders Tegnell, has become one of the most controversial men in Europe.

From the start, he insisted that mandatory lockdown was a waste of time. Sweden had a long-established plan for a pandemic, Mr Tegnell said, and was going to stick to it.

People should be sensible, wash their hands, avoid public transport and keep a safe distance, but that was it.

Closing schools was ‘meaningless’. Shutting borders was ‘ridiculous’. Masks were, by and large, a waste of time. Shops and restaurants should stay open.

Even as the virus spread, death rates soared and hospitals in Italy and Spain were overwhelmed, Sweden stuck to its guns. No lockdown.

The results were not perfect. Like us, the Swedes failed to protect their care homes.

By the time I landed in Stockholm, their death rate stood at almost 57 per 100,000 people, far worse than in neighbouring Nordic countries.

In fairness, though, Sweden is in parts more densely populated than most of Norway, Denmark and Finland, with three large cities in Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmo.

And Sweden’s death rate is still lower than those in Belgium (87 per 100,000 people), Spain (62), Britain (62) and Italy (58) — all of which did go into lockdown.

So what did I make of it? Well, that’s easy. After the negativity, paranoia, moaning and squabbling of Britain, Sweden was paradise.

The contrast struck me almost immediately at the supermarket. Usually the sky-high Scandinavian prices leave me wincing in anguish.

But this time I barely noticed them, too busy enjoying the lack of queues outside the shop, the absence of masks and the generally relaxed atmosphere.

Nobody recoiled in horror when our trolley came within five metres of them. Nor did people shrink in terror when another shopper appeared in the aisle, as is the norm in British supermarkets these days.

That set the tone for the next two weeks. For the Swedes, summer life has carried on as normal. Perhaps people give strangers a little more distance than they usually would — but so sensibly, so discreetly, that you barely noticed.

When we went kayaking in the gorgeous Stockholm archipelago, the guide told us that he was fully booked at weekends, even though foreign tourist numbers had plummeted.

Swedish foreign minister defends coronavirus strategySince most Swedes speak excellent English, we often asked people what they made of it all. And the answers were always the same.

Yes, they were sorry that the virus had got into their care homes. But without exception, the Swedes were glad to have escaped lockdown.

By this time, with the A-level shambles beginning to unfold back home, I was feeling miserable about the prospect of returning.

But perhaps the Swedish experience was too good to be true? I had a look at the latest figures to find out.

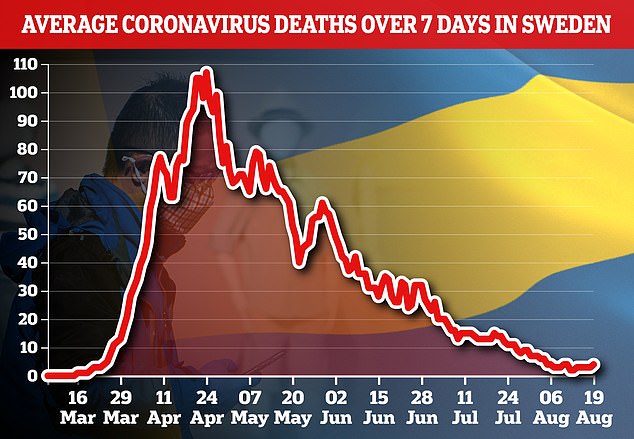

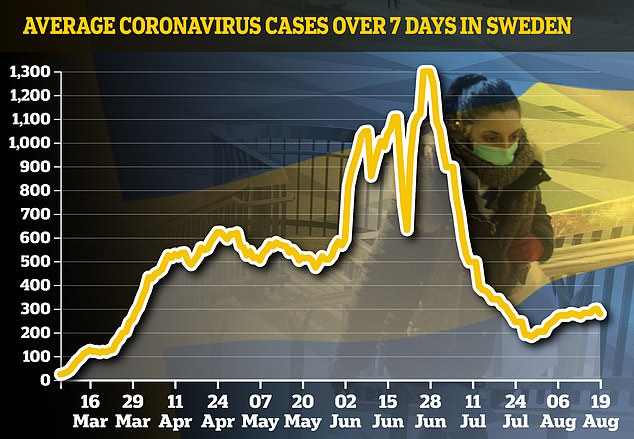

On August 3, the day we arrived in Stockholm, just one Swedish person was reported to have died of Covid-19. The next day’s death toll was three. The following day’s was 13; then it was down to six.

According to Sebastian Rushworth, an American-born doctor in a Stockholm A&E department, he hasn’t seen a single Covid-19 patient in a month: ‘Basically,’ he writes, ‘Covid is in all practical senses over and done with in Sweden.’ So should Britain have followed the Swedish example?

One obvious counter-argument is that Britain is even more densely populated, with almost 70 million people to Sweden’s ten million. Perhaps we were always going to need some sort of lockdown, if only temporarily.

In every other respect, though, I think the comparison shows us in an almost embarrassing light.

In the first three months, Sweden’s economy shrank by approximately 9 per cent — less than half the downturn in our own economy. Our children stayed at home; theirs went to school. Our businesses closed; theirs stayed open. Our social and cultural life ground to a halt; theirs continued — with some sensible restrictions.

At the top, the difference could hardly be more glaring. Sweden’s scientists drew up a plan, and their government calmly followed it.

Even as international criticism of his tactics mounted, Mr Tegnell remained calm. Again and again he repeated that there was no point in panicking, no point in making crowd-pleasing gestures and no point in committing economic suicide.

Contrast that with Britain’s politicians, floundering around like drunkards at closing time, flip-flopping on policy and constantly being dragged into ever more stringent measures to appease the public hysteria.

But perhaps it’s too easy to blame Boris Johnson & Co — who are, after all, merely a reflection of the society they serve. Mr Tegnell’s approach worked because the Swedes are a serious, sensible, law-abiding lot, who believe in individual responsibility and can be trusted to behave themselves.

Again, contrast that with the scenes here: first the panic-buying of toilet rolls; then the punch-ups in supermarket aisles and car parks; the absurd crowds on South Coast beaches; even the mobs of ‘anti-racist’ anarchists who thought a pandemic was the ideal time to rant and rave. All pretty miserable, I know.

And I can’t deny that when we flew back to face a fortnight’s quarantine, I felt distinctly depressed, not just at the thought of all those blasted masks, but at the prospect of all the Left-wing whining, Right-wing bickering, political incompetence and general irresponsibility ahead.

So in Scandinavian spirit, here’s a positive note on which to end.

Tragic as the death toll in Britain has been, it has not come close to the 250,000 predicted by Professor Neil Ferguson’s apocalyptic model, which reportedly inspired Boris Johnson’s decision to impose a lockdown.

So what did I make of it? Well, that’s easy. After the negativity, paranoia, moaning and squabbling of Britain, Sweden was paradise

The death rate has been declining for months — a 95 per cent fall since the peak in April. Coronavirus casualties are now six times lower than deaths from flu and pneumonia. In the week to July 31, just 2.2 per cent of deaths in England and Wales were caused by Covid.

Children don’t seem to suffer from the virus, or spread it much. Just one healthy child is known to have died from Covid in Britain, and there is not a single case recorded worldwide of a child giving the virus to a teacher.

We know who is at greatest risk (the very old, the very fat, people with Caribbean and Asian backgrounds or with underlying problems such as diabetes and lung disease), and our clinicians have got much better at treating and managing the disease.

There’s no reason, in other words, why Britain’s politicians can’t change the record — and they must do so fast, even if it disrupts their precious holidays.

For too long we’ve been ruled by paranoia. But economic logic and sheer common sense dictate that we can’t remain paralysed for a minute longer.

The priority now must be to restart the engines of enterprise and rebuild the economy. Life always involves an element of risk, and as long as we’re sensible, we need to get back to normal and free ourselves from our national funk.

So now is the time — albeit belatedly — for Boris Johnson to issue a call to arms.

He may fancy himself as the reincarnation of Churchill, but so far he has failed to match the great man’s courage at a time of national crisis. Now, more than ever, he needs to throw off his caution and rally the nation.

The truth is that for many of us, the last few months have been one long holiday from reality. But the summer is almost over and the economy is on life-support. It’s time we got back to work.

Source: DOMINIC SANDBROOK asks: Is Sweden proof we got it all terribly wrong?

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.