It was May 1994, and the long period of Conservative rule finally appeared to be coming towards an end. After pulling off one of the most significant electoral shocks of all time in 1992 — confounding the pollsters, commentators and bookmakers — John Major’s government was soon longing for the days of opposition. Britain exited the ERM, and with that the Tories’ economic credentials were shredded. Maastricht and the Euro set MPs against each other, while the hypocrisy of “Back to Basics” was exposed by a series of sex scandals.

Popular culture soon made up its mind about the decaying standards of public life. On television, politicians were increasingly portrayed as devious, scheming and morally reprehensible: from Rik Mayall’s cartoonish but compelling portrayal of Alan B’stard in the New Statesman to Francis Urquhart and his “confederation of connivers, bed-hoppers, drug-takers and manipulators” in House of Cards. By the mid-Nineties, Paula Milne had begun drafting The Politician’s Wife, a dark drama which would see a shameless Tory Minister rape, lie and cheat his way to the top (with the overarching aim of privatising welfare). “I really detest the Conservative Party and anyone attached to it,” admitted Juliet Stevenson, the show’s star.

As faith in Westminster reached critical lows, the Independent’s Andrew Marr observed how “the failure of so many familiar nostrums has left an uncertain people, suspicious of promises and temperamentally ready for betrayal”. But there appeared to be a new hope for salvation: a revived Labour Party, personified by its new leader, John Smith. He was clear about the moral slide in politics. “People expect the government to act in their best interests, and when things go wrong, they expect someone to take responsibility for it,” he argued in one speech. But, corrupted by a long spell in office, conservatism had had its day: “Their vision of humanity consists of individuals as decision-making units concerned exclusively with their own self-interest, making transactions in a marketplace.”

However, Smith’s message of renewal went beyond philosophical temperament and propriety. His mission was rooted in a desire to re-skill Britain, and equip it for the demands of the 21st century. He spoke about being “horrified” by the inequality that had arisen out of the Thatcher years: “The graffiti on the walls and a sense of decline and decay; people in sort of huddled ghettos of the poor and the disadvantaged.” He turned Thatcher’s language of decline onto the Britain she created. To turn it around, power had to leave London. “Our structures and institutions are clearly failing properly to represent the people.” It is a critique assembled by many an Opposition leader since — but it is revealing of their later inadequacies that Smith’s character and his legacy continue to loom over them all.

Smith’s route to the top was long and arduous — he’d first had to watch the devastation of the Thatcher years from within a powerless and self-destructive Labour Opposition. But while some ambitious colleagues broke away from the party, Smith stayed and played the long game. And by 1994, it appeared that his time had come. When the Daily Telegraph commissioned a wide-ranging poll on voters’ attitudes towards Smith’s Labour Party, the results were described by Anthony King as Labour’s “most encouraging news for more than a decade”. Smith had eradicated the party’s “loony Left” image and won the battle for economic competence. The data showed that people trusted him. Almost three-quarters of the electorate thought he had the “air of a family doctor or a bank manager” and looked like a man with “high moral standards”.

A campaigning mood was soon underway. And on the night of 11 May, Smith took to the stage in London to make the case that there was now “a great hunger amongst our people for a return to the politics of conviction and idealism”. But it proved to be his last act. The next morning, he suffered a heart attack and died later in hospital.

The political world mourned: the prevailing sentiment was that John Smith would have been prime minister and he would have been a great one. Giants such as Jim Callaghan lamented how the country could “ill afford to lose men of such excellence from our public life”. Fierce political opponents such as Norman Lamont compared him to Clement Attlee, arguing that he had “an inner steel and integrity which would have enabled him to make the tough choices that come with the job”. Margaret Thatcher agreed that it was a dreadful loss for the nation. “He was a thoroughly decent person,” and “had a good sense of what being British meant”, she admitted.

It would, of course, not have been so amicable had Smith actually lived to fight a general election campaign at the end of the Nineties. A Conservative Campaign Guide was leaked to the media in the days after his death that painted a very different picture. Activists were advised to attack Smith personally when door knocking. “His judgement has been entirely wrong on all the key decisions he has had to make in the last decade.” Another was that his leadership was “ineffectual and visionless” and “evasive”. Even within Labour, despite the poll lead, there had been fears that he had not yet sealed the deal with the electorate. The MPs most agitating for change were the so-called “modernisers”, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, who were increasingly influenced by how Bill Clinton had won in America. Alastair Campbell, then working for the Today newspaper, described the tension between the “modernisers” and Smith as a struggle between ‘“frantics” and “long gamers”.

Smith, famously, had little time for focus groups and the figures responsible for political marketing in Labour, Peter Mandelson and Philip Gould, were completely frozen out under his leadership. When asked why some critics believed he was dull compared to figures like Clinton, Smith argued that he didn’t give journalists what they wanted: “I don’t think politics is a sub-branch of showbiz.” He said he would refuse to begin “prancing around just being desperately interesting” to generate headlines. Smith’s death and Blair’s creation of New Labour firmly tilted the party in a different direction. The use of focus groups, the appeal to Conservative Britain and the courting of the media ensured that Labour’s victory in 1997 was emphatic. Few doubted that it was the right approach. And a narrative took hold — which has been heavily refuted by Smith’s former Chief of Staff David Ward — that Smith was too cautious and that a “one more heave” approach might have let the Tories in.

It wasn’t until the fifth anniversary of Smith’s death in 1999 that people began to wonder how differently things might have turned out. Channel 4 commissioned an alternative history in which Andrew Marr outlined how taxes might have gone up, Peter Mandelson would have been relegated to agitating from the backbenches, and the expensive “vanity projects” like the Millennium Dome would have been axed. In the real world, Anne McElvoy reported how many MPs told her: “New Labour was never really necessary and that the party has sold its soul for nothing.”

By the time of the Iraq War, Smith’s decency was sorely missed. After resigning from Cabinet, Robin Cook wrote a lengthy piece in The Independent on how Smith’s “honesty and integrity” would have created a different political culture. People would have trusted the government more. Most importantly, Cook concluded that Smith would have cross-examined the evidence on WMD to such an extent that nobody could have credibly made the case for war. His biographer, Andy McSmith, agrees: he would have sided with France and Germany over the United States.

The legacy of Smith, however, remains most suggestive on the issue of Europe. Smith was the first leader in the party’s history to be unequivocally and unashamedly pro-European. In 1971, he voted against the Labour whip in favour of membership. As leader, he ignored tabloid pressure to argue that “Europe is not just a marketplace”, but “a community”. And it was his view that the Eurosceptics, not the EU, had held Britain back. He argued that “wholehearted participation in Europe would undoubtedly bring benefits” to the nation. What that “wholehearted participation” really meant remains one of the great what-ifs” of modern British political history. Inevitably, Smith would have been faced with compromises — and accused of various betrayals — as all Labour leaders in office are. It’s not hard to imagine another alternative history where Smith fails to convince the public of deeper EU integration and helps turbocharge Britain towards the exit. Ed Balls, for example, has argued on his podcast Political Currency that had Britain entered the Euro under Smith, it would have been sunk by the 2008 financial crash anyway.

What is more important is how Smith still represents the ideal Labour leader for many people within the party. He is a rare figure from Labour’s past that is untainted by Left-Right factionalism, with Corbyn advisor Andrew Fisher and Blair advisor John McTernan both citing him as a model to follow. In the wreckage of the 2019 defeat, Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham argued that Labour needed to rebuild with a leader in the “mainstream tradition” like John Smith. Those close to Starmer, such as the Times columnist Phillip Collins, have argued that he is an heir to Smith, on account of them both having the “lawyer’s capacity to absorb a brief and press on the weak link in an opponent’s case”.

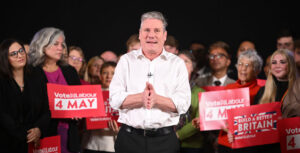

The test for Starmer, of course, will be whether he can live up to some of Smith’s ideals in office. In the 30 years since his death, the desire for Labour to decentralise Westminster, up-skill the workforce, move Britain closer to Europe and reform the voting system has only grown stronger. Starmer has borrowed from the Smith playbook to call for greater standards in public life: “To change Britain, we must change ourselves — we need to clean up politics,” he said in one speech. If he succeeds in doing so, he may finally put the counterfactuals about John Smith to bed. But failure will only make the desire for a different type of politics grow stronger.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/