Mindlessly scrolling through football transfer rumours on Twitter recently, I noticed some Liverpool fans trying something a little different. The club’s owners weren’t doing the business they wanted, so it was time, one fan suggested, to gather their mental forces and “manifest” a new midfielder. This wasn’t a joke, or a meme: if everyone could just come together and visualise it hard enough, Liverpool’s billionaire owners would stump up £150 million for Jude Bellingham.

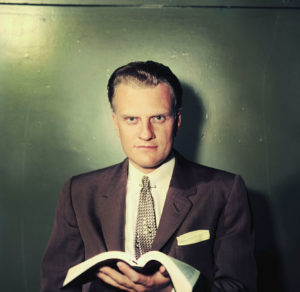

Their belief that their imaginations, combined with good vibes, could change another human being’s life channelled Norman Vincent Peale’s 1952 self-help classic, The Power of Positive Thinking: A Practical Guide to Mastering the Problems of Everyday Living. Peale was a Protestant clergyman, but his ideas have had an influence far beyond the American Church. The book has inspired not only football fans, but also prosperity preachers, presidents, new age spiritualists, celebrities and, now, TikTok influencers. Key religious texts aside, Peale’s guide, which has just celebrated its 70th anniversary, is arguably the most influential book in the world today.

Peale’s philosophy is a direct descendant of the 19th-century New Thought movement, promoted by Ralph Waldo Emerson and other thinkers of his day, which held that a healthy mind led to a healthy body and spirit. His “system of creative living based on spiritual techniques” was an instant success, thanks to his simple formula of prayerise, picturise, actualise. According to Peale, the “spiritual energy” of mind-power is on par with the science of atomic energy, and his simple three-step technique ensures that readers won’t be “defeated by anything”.

Peale knew his audience. Preaching out of Marble Collegiate Church in New York City, he spoke to a 4,000-strong congregation filled with successful, business-minded types, including a young Donald Trump, whose tyrannical father Fred lapped up the belief that a winner’s mindset could achieve anything. “It is appalling to realise the number of pathetic people,” Peale writes in prose that sounds jarring today, “who are hampered and made miserable by the malady popularly called the inferiority complex.”

Trump became a life-long advocate of the so-called “law of attraction”, which Peale summarises: “When you expect the best, you release a magnetic force in your mind which by a law of attraction tends to bring the best to you.” Speaking of his time in Peale’s church in 2015, Trump said that the pastor, who presided over his first marriage, would “bring real-life situations” to his sermons, and that “when you left the church, you were disappointed that it was over”.

Peale’s preaching may have been exceptional, but it was also representative of a fundamental shift in American theology. Positive Thinking was the final stop on American Protestantism’s journey away from Calvinism, the austere form of Protestantism that promoted the idea that we’re all degenerates and only God can determine who will be saved. As Europe and Asia smouldered, in the Fifties it felt like America’s time had come; there was no appetite for negativity, even in church. A new band of evangelical leaders began taking a greater role in mainstream American life, equally encouraged by the spirit of the times and fearing the spread of communism to their shores.

The Pentecostal movement, a branch of evangelicalism that was particularly strong among the working classes in the South and Midwest, had already experienced a theological revolution with the Latter Rain movement in 1946. Instead of tarrying, or waiting for the blessings of the Holy Spirit to fall upon them, they decided that they could receive God’s gifts on demand. “Ask and ye shall receive” was a mantra that encouraged a wave of faith healing — a practice that has an awful lot in common with manifesting.

More radical shifts were to come. In the Fifties, preachers such as Oral Roberts began to popularise the prosperity gospel: the idea that God rewards you for giving money to your church and pastor. In “seeding” these donations, followers plant an act of faith that then grows a material harvest.

This idea thrived in large part thanks to the highly respectable Peale presenting them in a wholesome package. Kate Bowler, author of Blessed: A History of the American Prosperity Gospel, calls Peale the “principal prophet of this generation” — one who transformed “abstract theology into workable wisdom”. With a syndicated newspaper column that attracted 10 million readers, and radio and television programmes that stayed on-air for decades, his message was broadcast across the nation. The Power of Positive Thinking stayed on the New York Times best-seller list for three record-breaking years, selling a million copies.

Bowler believes that Peale’s “synthesis of upward mobility with religious buoyancy matched the postwar mood, turning a man into a movement”. An energetic new generation of evangelists, such as Kenneth Hagin and Reverend Ike, heard the call. They, too, used new media such as syndicated radio to take this relatable, optimistic form of Christianity to the masses.

According to prosperity preachers, God cared about the size of your pay packet at the end of the week. Christ was actually wealthy, they claimed. A donkey was the equivalent of a Cadillac back then; Baby Jesus was famously bestowed with gifts; His guards at the crucifixion were a sign if his high status.

While only the boldest evangelists in America, such as Joel Osteen and Creflo Dollar, continue with this line of preaching today, the prosperity gospel has real currency elsewhere. Neocharismatic Pentecostalism’s rapid expansion in Asia, Africa and Latin America is thanks in large part to the promises it makes, of health and wealth. In the slums of Sao Paulo and Lagos, the idea of one day reaping the rewards of giving a little money and having a lot of faith is the only opportunity to succeed that most people can imagine.

And, just as there are some health benefits to seeing the glass half full, there’s a growing body of evidence that adherence to the prosperity gospel sees an uplift in people’s circumstances. Research in Latin America has found that people who have experienced poverty, violence and addiction have a greater chance of escaping those cycles by joining an evangelical church. In Brazil, researchers found that when the GDP goes down, attendance at evangelical churches increases, and that the support networks available at those churches further support a politics that says people should seek a hand up, and not a hand out.

Of course, this phenomenon is far from limited to the faithful poor. In the United States alone, the self-help industry rakes in around $10 billion annually, with Peale’s work something of a Rosetta Stone for a field that relies on good vibes. But it was Australian television producer Rhonda Byrne who reintroduced The Power of Positive Thinking to a new, global audience in 2006 with her film and book, The Secret. Though Byrne claimed inspiration from Wallace Wattles’s 1910 book The Science of Getting Rich, “the secret”, we find out, is a familiar three-step solution: “ask, believe, receive”. A sexier version of Peale’s prayerise, picturise, actualise, in other words, and more than an echo of Matthew 21:22: “And all things, whatsoever ye shall ask in prayer, believing, ye shall receive.”

The secret also employed Trump’s favoured “law of attraction”, whereby positive thoughts attract positive things — in Byrne’s case, that included selling more than 35 million copies worldwide, endorsements by Oprah Winfrey, and a reported $300 million fortune. She also has the honour of being the person who introduced the concept of “manifesting” thoughts into things to a mainstream audience. In one chapter on the body, Byrne writes that “it is your thought that food is responsible for putting on weight that actually has food put on weight”.

Whereas most of Peale’s case studies were about people gaining confidence and finding success in life, Byrnes’ focus appears to be much more centred on realising material goods, like better cars and houses, or more money — reframing self-help for a new audience who had come increasingly to define themselves as consumers. Now, you didn’t even need biblical justification, or New Thought virtues. You could simply “ask, believe, receive”.

A toddler can prod the premise with a stick and see it fall apart. What if everyone who buys a lotto ticket imagines themselves winning it and says a prayer? Has no one who has died from cancer ever sincerely wished it away? But Byrne, who says that “the secret” has been understood by everyone from Buddhist monks to Shakespeare and Einstein, was, much like Peale, the right person at the right moment.

A “spiritual but not religious” type in a secularising world, her suspicion that elites were hiding this great truth from ordinary people appeared to be prophetic. Byrne came to prominence shortly before the 2008 financial collapse, which destroyed Americans’ faith in something that had been a fundamental: the idea of an ever-growing housing market. Many turned to Byrne’s renegade optimism as a result.

It should come as little surprise, then, that the next great global shock saw a resurgence in “manifesting”. In March 2020, as the pandemic locked most of us in our homes, videos about “369 manifesting” began appearing on TikTok, amassing hundreds of millions of views. The idea here is that people need simply write down what they’d like to manifest three times in the morning, six times during the day, and nine times at night. Pop star Lizzo is one of many celebrities who preaches the benefits of thinking your way to success; she told one interviewer that “you can manifest your life and speak things into existence, if you have positive goals and affirmations for yourself”.

TikTok manifesting has launched a variety of new techniques, including “wouldn’t it be nice” and ”the law of assumption”, which provide new ways to ruminate on getting what you want. The practice appears equally popular with men and women alike, with not only Lizzo but also hopeful Liverpool fans and manosphere influencers such as Andrew Tate getting on board. For young people who feel cheated out of two important years of their lives, and conventional job and housing opportunities looking evermore slim, the resurgence in positive thinking is easy to understand. Having the right mindset might be the only thing they feel they have control over.

And crucially, the practice is flexible. You can call it positive thinking, the secret, or manifesting. It can be spiritual or religious, or dressed up as pop psychology. A variety of activities can fall into its remit, including journalling and vision boarding, and there is a wealth of new manifestation practitioners offering podcasts, coaching and online courses — almost always cutely priced at numbers like $2,222, given that manifesting and numerology seem to go hand-in-hand.

That manifesting has taken a turn for the capitalist is telling. The enduring influence of The Power of Positive Thinking points to an essential human trait: we seem hard-wired for magical thinking. But it also reveals something far grimmer. The closest that we can come now to divining the will of God, or the energy of the universe, is by noticing who gets what they want. And the closest we come to practising devotion is to imagine getting it.

***

Order your copy of UnHerd’s first print edition here.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/