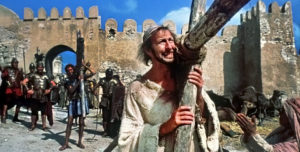

In Lapland, just inside the Arctic Circle, you can visit Santa Claus at any time of year, because that’s where he lives. No doubt this requires a plentiful supply of Santas (I hope nobody under the age of seven is reading this), some of whom may be graduates of a course in Santa Claus studies you can take at the University of Lapland. Like Santas everywhere, you need a generous girth, a certain facility with the ho-ho-hos, a lack of lurid facial tattoos and no history of paedophilia. I once saw such a generous-girthed image of Santa Claus in a shop window in Beijing, at a time when a newly modernising China was getting to grips with Christmas. The fact that he was pinned to a cross suggested that they still had some way to go.

There are other myths about Christmas, this time Biblical ones. We read in the New Testament that Mary and Joseph had to leave their native town of Nazareth and travel to Bethlehem, which is where Jesus was born. They did so because a Roman census of the population required that all citizens should return to their birthplaces in order to be counted. Since Joseph, Jesus’s father came from Bethlehem, this was where the couple ended up, with Mary on the verge of giving birth to her baby.

Having everyone return to their birthplaces seems a mighty odd way of holding a census. Why not just count them on the spot? Such a project would have gridlocked the Roman Empire from end to end, since the census is said to have involved the imperial world as a whole. The upheaval would have been spectacular — so much so that we would almost certainly know about it from non-religious sources. But we don’t; no ancient historian records it. And this is almost certainly because it didn’t happen. The census is probably a narrative device for getting Jesus born in Bethlehem. Bethlehem was King David’s city, and prophecy foretold that the Messiah would come from there. It would be embarrassing for him to hail from a scruffy little place called Nazareth in the benighted rural region of Galilee. It would be like nominating someone from Barnsley as President of the Universe. (To avoid a deluge of threatening letters, I should add that Barnsley is a brilliant place to live.)

There is another anomaly here, however, since Jesus wasn’t really the Messiah at all, even if you believe that he was the Son of God. In Jewish tradition, the Messiah is a secular figure rather than a sacred one — a mighty warrior who would lead the Jewish people to victory over their enemies. The job description doesn’t fit Jesus at all, and on no occasion in the gospels does he unambiguously acknowledge the title (or, for that matter, the title of Son of God). His entry into Jerusalem on the back of a donkey looks like a satirical parody of a triumphal royal procession. He spurns what St John calls “the powers of this world”, meaning among other things the dominant political set-up, and is brought to his death by them. Politically speaking, he is a failure, executed by the imperial state and deserted by his comrades. So maybe Mary and Joseph’s winter journey to Bethlehem wasn’t necessary after all.

As even Richard Dawkins is aware, Jesus was born in a stable because the Bethlehem lodging places were full. Perhaps in honour of this occasion, hotel accommodation at Christmas continues to be scarce. Not long after his birth the child is visited by three kings, or so popular belief has it. In fact, the New Testament doesn’t mention how many of them there were, and in any case they weren’t kings at all. They were Magi: magicians, sorcerers, fortune tellers, the kind of charlatans whom rulers used to hire to bedazzle the common people with their conjuring tricks. They were also astrologers, enemies of human freedom who maintained that everything was predestined by cosmic forces, and who peered into the future in order to reassure their sovereign that his power would continue to flourish for years to come.

Why should such unsavoury characters come to visit a new-born child, the offspring of a couple of nobodies? The clue may lie in the gifts they brought with them, which were probably not gifts at all but tools of their esoteric trade. What they are probably doing is not laying down presents at the baby’s feet but surrendering the tokens of their power. The scene, in the words, may be allegorical, as the old regime of fear, awe and superstition gives way to a new world of freedom and friendship. This is how T.S. Eliot sees the matter in his poem, “Journey of the Magi”:

…this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

Also present at the birth are a group of shepherds and a choir of angels. The angels signify infinity, while the humble shepherds are of the earth. The angels are countless, the people are counted and the shepherds don’t count.

To be humble, however, counts for a lot, at least for the New Testament. During her pregnancy, Mary pays a visit to her cousin Elizabeth, who is also pregnant. Neither woman is an image of conventional domesticity: Mary and the child she is carrying aren’t dependent on what the gospels call “the will of man”, which is to say that this mother-to-be is a virgin, and Elizabeth is beyond conventional child-bearing age. When she sees Mary, we are told that the child in her womb leaps for joy. He won’t, however, be joyful all that long.

The man he grows up to become is known to history as John the Baptist, who will be beheaded by King Herod, while Mary’s child will be executed by the occupying imperial power. Neither man has much time for the family, a set-up of which Jesus is consistently critical. When informed that his family wish to see him while he is preaching, he tells them brusquely to wait. His mission takes precedence over domestic ties. He has come not to unite families, he announces, but to divide them. John seems to have no kinsfolk at all, hanging out in the desert on a diet of locusts and honey like a refugee from Woodstock. Both men are vagrant, celibate, without home, property, profession or — as it turns out — much of a future.

Mary’s encounter with Elizabeth is staged by St. Luke (we have no idea whether it actually took place), and is one of the most astonishing scenes in the New Testament. In a sisterly dialogue, Mary bursts out in response to Elizabeth’s greeting with a passage from the Hebrew Scriptures. Perhaps she sings and dances as she does so; God, she declares, “has brought down the mighty from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; he has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he has sent empty away”.

As an obscure young woman from nowhere in particular, Mary is comparing her own elevation to the status of mother of Jesus to the raising up of the poor. She is making a political point out of her pregnancy. Some scholars even claim that the words which Luke puts in her mouth are part of a Zealot chant, the Zealots being underground revolutionaries who were eventually to strike against Rome with calamitous results. Whether or not Mary’s cry is Zealot-inspired, it is almost a platitude of the Hebrew Scriptures: you will know Yahweh for who he is when you see the downtrodden coming to power. The only authentic power is one which is born of weakness.

The poor in the Bible are sometimes called the anawim, the scraps and leavings of the earth; and in an extraordinary gesture, Luke is here turning Mary into a sign of them. As a symbol of the powerless, no woman could be more powerful. Women as a whole belonged to the dumped and discarded in first-century Israel, and Mary becomes a representative of them by being raised up to freedom and dignity. The other prominent Mary in the gospels is Mary Magdalen, who despite the fact that she may well have been a prostitute is allotted the privilege of being among the first to discover that Jesus’s tomb is empty. Her testimony to the fact is officially worthless, since women were not recognised at the time as valid witnesses.

It’s all a long way from mince pies and paper hats. Still, there’s something to be said for the turkey and the trimmings. What we have retained from Mary’s jubilant chant, however dimly and distortedly, is the fact that Christmas is about rejoicing. In the depths of the dead season, new life begins to stir, and from the most unexpected of quarters. If the best we can do to recall that spirit is the gift of a new pair of socks, well, that’s the modern world for you.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/