In the strangest of times, the strangest of festivals. Dulled by familiarity, piled over with good food, buried in torn wrapping paper, drowned in good drink: can we see Christmas again for what it is?

In days that seem unprecedented, we cling to the familiar. I do, anyway, and Christmas has been familiar to me all my life. The excitement and the anticipation that I felt as a boy is felt now by my young son, and I can live vicariously through him: the lack of sleep, the mince pies for the reindeer, the presents waiting, if he’s lucky, under the tree. Christmas has its rituals, and we don’t have many shared rituals left in the modern West.

But the rituals disguise the radical strangeness of the claim that Christmas makes, and the radical strangeness of the religion that makes it. That God took human form, that he was born into persecution and poverty, that he came to put the world back into its right shape. That this God does not demand burnt offerings, but will instead sacrifice himself to correct our errors. That He shows us a path both straight and narrow and leaves it to us to decide whether to follow it. A virgin birth in a cave, a risen corpse and an empty tomb: there is no sense in any of this. None of it is normal, even by religious standards. It is some kind of revolution.

But here we are, celebrating it with turkey and crackers, and yet not really celebrating it, because — well, because this is now, and that was then. We all know that Christmas has become a commercial horror show: complaining about this is another part of the ritual. We all know that most of us will barely genuflect towards the Christ whose mass this once was: hearing bishops lamenting this is also as traditional as watching the Queen’s Christmas message, or refusing to watch it and reading the Guardian in the corner instead.

The world has been upended these past two years, and it feels to me as if the ructions, which are far from over, are not merely temporal. It feels like we are being shaken out of some slumber; as if the spirit is on the move. Perhaps I feel this way because of the unexpected turn my life has taken, coincidentally or not, during the corona era. Just over a year ago, much to my own surprise (and initial resistance) I became a Christian. Some people might call it a “conversion”, which always sounds a bit shiny-eyed to me, but I didn’t really feel like I’d converted to anything. I felt like I’d come home. I can’t explain it, though I keep wanting to.

It is always ridiculous to write about religion. When I say “ridiculous,” I mean “dangerous”, I think: dangerous in the West, anyway, which is the only part of the world in which the rejection of religion and the denial of God has ever really taken off. This does not seem to be working out well for us, but try talking about that in public. Since I became a Christian, and as the daily practice of the faith has deepened my understanding of it, I have found it harder and harder to relate the Christian worldview to the worldview I used to have, and which the culture around me encourages in us daily. This is not just a Christian problem: everyone I know who follows a faith seems to understand it. It might just be a manifestation of how new I am to this, and how inadequate my understanding is. Still, the gap between the world and the Way — as the early Christians called the path of Christ — seems more and more like a widening gulf.

This will be my first Christmas in the church. The Orthodox church, into which I was baptised just under a year ago, has a deep and old and demanding practice around this festival of light. For the last forty days, we have been fasting: today the fast is broken. A child is born, and everything has changed. The birth of Christ marked the beginning of a new age. The Orthodox church talks of Jesus of Nazareth as the “second Adam”. The first human messed up by rejecting God — by choosing control over communion, and falling into self-love. The incarnation of God in human form corrects the error: we get a second chance to turn from ourselves and look to the greater whole.

It is, as I say, a strange story: frightening, glorious, thrilling, radical, impossible, repulsive to some. Jesus remains the most controversial man in history, and his followers have always been looked at, like him, through narrowed eyes. Here in the West we are still emerging, both psychologically and structurally, from a period in which Christianity was associated with authority: with power and Popes and state churches and holy wars. Now that this authority has been overthrown, Christians are increasingly regarded again as they were for the first four centuries of their existence: with suspicion, if not open hostility.

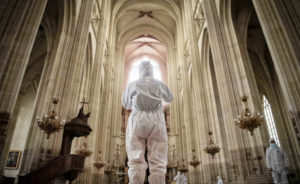

Some Christians regret this, and long for the return of a West in which church and state again hold sway in tandem: a world of faith, in which the people live, at least in theory, by the way of the cross. I understand this: it’s an enticing vision. I would like to live, I think, among the symbolic splendour of the high medieval Christian world. Certainly I’ve never felt comfortable in this one. But for better or worse, that world is not coming back, and it seems right that a faith built on sacrifice and renunciation should again require some of its followers. Throw down your nets and follow me. If the world hates you, know that it hated me first. The Way was never supposed to be comfortable. Christ and power don’t mix.

This is how it seems to me, but I am still new. One thing I have learned though — or had brought home to me, because I knew it before I became Christian — is the necessity of ritual in a human life. One reason I joined the Orthodox church, despite being an Englishman who lives in Ireland, was because of its deep understanding and practice of this. We reject ritual in the modern West. We don’t see why we should submit to any authority or respect any tradition. We believe that every one of us can invent the world anew. We are wrong about this, as we are about much else.

The rituals of the Orthodox church are sometimes florid and always long, and like Christianity itself they can look strange or off-putting from the outside. But the first time I attended a divine liturgy, I knew where I belonged. Something had happened to me that I couldn’t put my finger on. This service, largely unchanged for 1600 years, has a spiritual and psychological impact that can’t be outlined in essays or explained in words at all.

Church rituals, like those of all religions, fit into a wider pattern — that of the ritual year. As a Christian celebrating my first real Christmas, I have come late to the realisation of how much this matters. I think this is why many Western Christians hanker for the Christendom that is gone: not because they desire power, but because of the container, the guiding light, that the ritual year offers, and because they see what we have lost by abandoning it. Christmas, Lent, Easter, Whitsun — we still know the names, but we are long detached from the symbolic pattern they provided, and the understanding of our place in the universe that they formalised in daily life. What comes together in the bread and the wine, changed into the flesh and the blood — this can never be replaced with turkey and sherry.

Something is missing here, and not just for Christians. I have come to believe that humans are above all religious animals. If we do not have a religion, we will make one for ourselves, or substitute politics or ideology for it, to assuage our need for ritual, worship and meaning. But ideology or self-help can’t fill the gap, because what is missing is the thing we are all fleeing from, like the fire it is. The real meaning of Christmas, I think, and maybe the real meaning of all faith, is simply: look up. Raise your gaze. When we lose the religion that made us, and the rituals that contained it, however imperfect those things were, we lose our understanding of the heart of the matter, the thing we turn from and scorn and then are returned to because nothing else will fit into the empty space in our hearts: God.

Good, say the atheists, about time. I disagree. I think that understanding that there is something higher than us — that we are part of a greater pattern, that a higher intelligence is at work, that we are not in charge and that this is good. I think that without this understanding we find ourselves back in the garden, tasting the apple all over again, every day of our lives. We choose self over other, control over communion, power over sacrifice. Of course we do: we all do. We want to walk that way. But I think we can see now where it is leading us.

Like I say, it is ridiculous to write about religion. Ridiculous for me, anyway. But there is nothing else I can say today. It is deep winter, but some light is rising. It has been rising for a long time. Everybody should celebrate today, whatever they choose to raise a glass to. It has been a hard year. I will try to turn my scattered mind, before the feast and after, to the words that made us, and which still linger in the air, waiting to settle on the holy and the profane, the weak and the strong, the willing and the broken and the unsuspecting:

Be of good cheer, I have overcome the world.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com