It is there in bold, red letters on every foreign visitor’s entry card: “Death for drug traffickers under Singapore law.” Once they’ve made their way past the indoor waterfall, passengers leaving the nation’s only commercial airport might catch a glimpse, at its perimeter, Changi Prison. First established by the British colonial government, it is here that Allied prisoners of war were held by the Japanese. Now, it is the place where drug traffickers are hanged at dawn.

One of the handful of democratic states that still carries out the death penalty — a club that also includes the US and Japan — Singapore executed 11 people last year, making it one of the 10 most prolific judicial executioners in the world. The dawn hangings were put on hold during the pandemic, but the state is now catching up on its backlog, with three carried out in recent weeks, including the first execution of a woman in almost 20 years. Saridewi Binte Djamani, a 45-year-old Singaporean, was put to death last month, having been found guilty in 2018 of possessing “not less than 30.72 grams” of heroin.

The death penalty, mandatory for a range of offences since 1975, has long been held up as a sign that this prosperous island has a dark side. Less commented upon are the disparities it magnifies, which call into question one of the country’s most cherished central claims — that it is a meritocracy, with advancement open to anyone, regardless of their background.

Singapore is a multi-racial blend: ethnic Chinese make up around three-quarters of the population and dominate the highest positions in politics and business. Malays are the next largest ethnic group, while Indians are the third. While all racial groups have benefited from Singapore’s soaring economic growth since independence, Malays have lagged behind; Malay households have the lowest income, on average, of the three ethnic groups. Last year, a group of UN experts expressed concern that a “disproportionate number” of those being sentenced to death for drug offences came from racial minorities and poorer backgrounds. Between 2015 and 2020, 44 people were sentenced to death in Singapore for drug offences. Of those, four were Chinese, three were Indian and 37 were Malay. All three of those executed in the last few weeks were Malay.

But not all drug dealers are equal in the eyes of the city-state. Lo Hsing Han, one of Myanmar’s richest men and, according to the US government, “one of the world’s key heroin traffickers” had strong financial ties with Singapore until his death in 2013. His daughter-in-law owned 10 companies there, all of which were sanctioned by the US in 2008. The US government also found that Lo’s conglomerate, Asia World, provided “critical support” to Myanmar’s military junta. According to Lo’s obituary in The Economist, by 1998, more than half of Singapore’s investments in Myanmar were made with Asia World.

Singapore is now a democracy, but one with an unusual compact between state and people. After independence in 1965, in the space of a few decades, its founding prime minister Lee Kuan Yew and his successors transformed Singapore from a colonial port into a global manufacturing hub and financial centre. It is a comfortable place to live, with low unemployment, high-quality state-built housing, an exceptional public-education system and one of the world’s highest life expectancies, at 83 years. There is a fairly high degree of personal freedom, though political debate is tightly circumscribed. Singaporeans are, in general, content to accept this bargain, raising few questions about the way things are run.

For those who do, the consequences can be harsh. There is little space for protest. A few years ago, an activist named Jolovan Wham was charged with illegal protest after standing outside a police station holding a cardboard sign with a smiley face drawn on it. Ministers take an unusually prickly view of critics, with a history of successfully suing bloggers, foreign media and political opponents for defamation. While elections are free and fair, the press is largely fettered — nowadays, by self-censorship in newsrooms. There is limited scope for campaigning that challenges the government.

Nevertheless, Singapore has always had plenty of foreign admirers, among them Donald Trump. At his 2024 campaign launch at Mar-a-Lago last year, Trump called for drug traffickers to be executed and said the US should look to Singapore. “Singapore has no drug problem. They don’t even know what you’re talking about,” he said. It’s fair to say that drug misuse is small-scale; last year, Singapore, a country of 5.6 million, arrested 2,800 people for drug abuse.

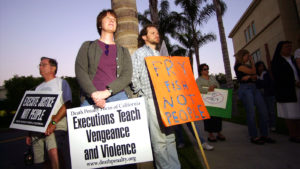

The government says there is overwhelming public support for maintaining the death penalty, citing surveys that find around three-quarters of those polled support capital punishment for the most serious crimes. But that consensus might be fraying. In April last year, around 300 people attended a candlelight vigil for Nagaenthran Dharmalingam, a 33-year-old Malaysian man convicted of trafficking 43 grams of heroin, a few tablespoons of the drug that were found strapped to his thigh when he entered Singapore. His lawyers had argued he had a learning disability and had been coerced into carrying the package.

The vigil for Nagaenthran took place in Hong Lim Park, a small patch of greenery on the edge of Singapore’s financial district, and the only place in the country where citizens are allowed to protest without a police permit. His family was not allowed to attend, as foreign nationals are barred from joining such demonstrations. He was executed two days later.

Nagaenthran’s case attracted international attention, with Richard Branson among those deploring the execution and describing him as a victim both of drug cartels and a “justice system that so consistently seems to fail minorities”. A few months after the hanging, Luke Levy, a National University of Singapore student, walked on stage for his graduation ceremony and pulled out a piece of A4 from his gown pocket with a message protesting “state murder”. Levy was edited out of the video of the event (his university said the ceremony was “not a forum for advocacy”). He is not alone, though. Earlier this month, graffiti against the death penalty — featuring a syringe and a hanged man grasping a dollar sign — appeared in an underpass outside a metro station, a bold act in a country where graffiti can be punishable with up to three years in prison and corporal punishment, delivered with a rattan cane.

Kirsten Han, 34, a journalist and activist, tells me that, growing up in Singapore, she was happy to accept the view that the death penalty was necessary for public safety: “I had the impression that the people on death row would be those running drug syndicates and making huge profits, and that it would be possible to eliminate the trade through punishment.” She is now a prominent voice against capital punishment. It was volunteering at The Online Citizen, an independent news site, that brought about her epiphany: “It was my first opportunity to read up about the law, meet the family members of people on death row, and get to know the lawyers and activists working on this issue.” Han says, as a Singaporean, campaigning for the abolition of the death penalty has involved “a lot of unlearning”.

In the face of criticism, Singapore’s politicians tend to be thin-skinned. Lee Kuan Yew — who died in 2015 — had studied law at Cambridge before being called to the Bar in 1950, and frequently addressed his political opponents with a truculent barrister’s courtroom swagger. “Human rights?” he once asked. “Are they bankable?” This tradition of verbal sparring has been taken up by K. Shanmugam, another lawyer, who is the long-serving Minister for Home Affairs. He recently swatted down opponents of the death penalty as “narco liberals”.

Lee liked to argue that Confucian traditions imbued Singaporeans with a strong allegiance to the group and a reverence for scholarly leaders. It was a rewriting of Singapore’s turbulent history, which included violent labour disputes when the country was breaking away from colonial rule. But it allowed him to present a convenient narrative that challenged what he called “the unlimited individualism of the Americans”.

More recently, in response to a question about press freedom, prominent Singaporean statesman Tharman Shanmugaratnam said there were other kinds of liberty: “You aspire to the liberty of living in a city that is not defined by its most disorderly elements,” he said. Yet its reluctance to budge on capital punishment has made it something of an outlier in the region. Thailand has scrapped the mandatory death penalty for drug trafficking, Malaysia is observing a moratorium on all executions, and penal reforms in Indonesia have created the possibility of commuting death sentences after 10 years if a prisoner maintains good conduct.

Such shifts make it harder to defend an absolute position as an exemplar of stern “Asian values”. But there are signs that moderation is creeping into Singapore’s dispensation of justice. Last year, a drug courier’s sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by the Court of Appeal, after judges found that his depression and substance use had combined to impair his mental responsibility.

But Singapore doesn’t have much incentive to make changes. In the face of current geopolitical tensions, it is unusually well-placed to prosper. Hong Kong, its old rival as Asia’s main business hub, is now firmly in Beijing’s authoritarian grip. This makes Singapore one of the few places on the continent that can steer a line between the world’s two superpowers: it has a defence partnership with the US, but close economic ties with China. It’s a place where both Western and Chinese businesses are comfortable setting up regional HQs — like Vienna in the Cold War, but with better noodles. One consequence of this is that Singapore is fairly impervious to external criticism, its rulers more comfortable than ever in defining liberty according to their own measures. And even if Singaporeans have been increasingly assertive in recent years, wanting more of a say in how their country is run, for most citizens, the death penalty infringes little on their personal liberty.

And yet, there may be a push for greater latitude on recreational drugs from Singaporeans, who have observed the relaxing of laws in the West. Singapore’s present and future success is bound up with white-collar jobs in finance, coding and hi-tech manufacturing that require education and a degree of independent thinking. A population that’s encouraged to use their initiative at work is less likely to accept a strictly “just say no” position from their government.

Change might also come from the top. When it comes to the sin businesses, there’s a precedent for shifting official attitudes, especially when there are dollars to be generated. Gambling was once frowned upon, feared for its potential to corrode the nation’s work ethic. But the government changed its mind, ostensibly to boost tourism. If arguments based on the freedom to choose don’t wash, the economic imperative could drive Singapore to loosen up on cannabis at least. The country is unlikely to let go of the death penalty, in part because it is a marker of Singapore’s identity — more ruthless than those soft Europeans. But if laws for some drugs are relaxed, there may be fewer occasions when it needs to be imposed.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/