When Micheál Martin visited Mount Scopus on the outskirts of Jerusalem two months ago, he struck a pessimistic tone. The Irish government’s deputy head had been taken there for a briefing by UN officials, who told him the number of Palestinians killed by Israelis in the first half of 2023 was two and a half times higher than in the same period last year. There has also been a marked increase in the demolition of Palestinian homes, officials told him, pointing to locations in the distance where Israeli settlers were building properties.

Martin, who by that time had met with the presidents of both Israel and the Palestinian National Authority, had two main objectives. The first was to reinvigorate the push for a two-state solution, which had stalled partly due to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and partly due to the election of a hardline Israeli government in 2022. The second objective was almost as ambitious. Martin sought to convey the message that Ireland, contrary to common perception, was a friend of Israel. Dublin may speak louder than most in favour of Palestinian rights, but that doesn’t mean it is blind to Israel’s security needs, he argued.

The Israelis weren’t convinced. There were niceties and handshakes, but the Irish delegation was met with an undeniable coolness in Jerusalem. Israeli diplomatic officials repeatedly expressed frustration to Irish journalists that Dublin was far quicker to condemn the actions of the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) than those of Palestinian militants. “When Hamas kills Israelis, why are they not called terrorists in your newspapers?” one asked.

Before departing for Jordan, Martin attempted to put a positive spin on the visit, expressing hope that a plan to restore relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia may enable some progress on the Palestine question. Now, in the wake of Hamas’s barbaric October 7 attack and the devastating IDF response that has left thousands dead in Gaza, that hope seems to have been misplaced. Not only is the two-state solution more distant than ever, but Irish-Israeli relations are at perhaps their lowest point in history — lower even than in 2010, when Dublin expelled an Israeli diplomat in response to Mossad agents using Irish passports during the assassination of a Hamas official in the UAE.

Since the start of the Israeli bombardment of Gaza, Ireland, along with a small number of EU countries, has been pushing for a ceasefire, instead of the “humanitarian pause” favoured by the EU as a whole. And as the death toll climbs, the Irish government’s rhetoric has gradually strengthened. Earlier this month, Varadkar said Israel’s response has gone beyond self-defence and “resembles something more approaching revenge”. The Taoiseach ducked the question of whether Israel is guilty of war crimes, but noted that “the targeting of civilians, collective punishment: these are breaches of humanitarian law whoever commits them”. Martin, who is Varadkar’s coalition partner, is usually more careful with his words, but even he has called Israel’s attacks “disproportionate” and “not necessary”.

At this autumn’s Fianna Fáil party conference, the Israeli ambassador to Ireland Dana Erlich likely felt uncomfortable listening to Martin strongly criticise her government’s actions. (The Palestinian representative sat a few seats away.) In the same speech, Martin rejected calls from Sinn Féin to expel her. But his main rationale was that diplomatic channels must be kept open to negotiate the extraction of some 40 Irish passport-holders from Gaza. It’s a far cry from the warmth shown to the Israeli diplomatic corps in most other EU capitals. Israel’s foreign affairs minister Eli Cohen said, last month, that Erlich is “representing the State of Israel in one of the more challenging arenas for Israel in Europe”.

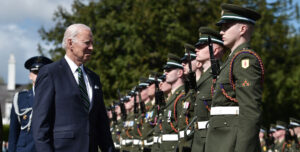

That relations between Ireland and Israel are so poor is perhaps surprising, given the two nations’ extensive historic links. Israel’s sixth president, Chaim Herzog, was born in Belfast in 1918, to Ireland’s chief Rabbi, a vocal Irish nationalist and fluent Irish speaker. The current president, Isaac Herzog, is Chaim’s son. During Joe Biden’s visit last year, the two bonded over their shared Irish heritage.

Ireland also has a history of supporting and inspiring the Jewish fight for religious freedom. Near the town of Nazareth is Éamon de Valera Forest, named in recognition of the Irish leader’s support for the Jewish people, whom he explicitly protected by inserting a clause in Ireland’s 1937 Constitution. And in the Forties, Jewish independence fighters explicitly adopted guerrilla tactics that were used by Irish revolutionaries. Israeli leader Yitzhak Shamir even assumed the nom de guerre Michael, after his Irish counterpart Michael Collins, during his country’s formative struggle for independence.

Still, commentators can easily point to darker moments in Irish-Jewish relations. For instance, after Hitler took power, Dublin refused to admit refugees fleeing Germany, with one Irish official stating they had “to some extent… brought the trouble [on] themselves”. And then there was de Valera’s extraordinary ill-judged visit to the German legation to pay his condolences on Hitler’s death, a fact that was unsurprisingly not mentioned when an Israeli forest was dedicated to him, but which frequently appears in the Israeli press.

However, it is Ireland’s support of Palestinians’ rights, rather than its patchy record of supporting Jews, which has defined its relations with Israel. Officially, Dublin has yet to formally recognise a Palestinian state, despite both houses of parliament backing such a move. But in recent months, as Israeli settlers have increasingly and illegally encroached onto Palestinian land, Martin has signalled that he is open to progressing formal recognition — something no other country in western Europe has done.

There is also significant support for Palestinian rights at a local government level. On Monday, Dublin city council debated a motion to fly the Palestinian flag over City Hall for a week in a show of solidarity (it received majority support but failed to meet the required three-quarters of the vote). In its place, lampposts across the capital have been adorned with stickers in support of Palestine. Last week, pro-Palestine activists occupied the Department of Transport, calling on the Government to “stand with the Palestinian people by halting any transportation of weapons bound for Israel” through Ireland.

Why do the Irish people support Palestine so passionately? The received wisdom is that Ireland sees its own struggle for independence reflected in that of the Palestinian people. Indeed, the Palestinian flag is a common sight in nationalist areas of Northern Ireland, and it is not unusual to see an Irish Tricolour flying in Ramallah or Gaza. But the full explanation is more prosaic. As a small, democratic nation with no real military power, Ireland is very invested in maintaining a rules-based international order, as opposed to a more muscular geopolitics. Hence the full-throated support for Ukraine.

Another cornerstone of Irish foreign policy is consistency. Our diplomats tend to take the view that core positions on international conflicts should not change overnight, no matter what narrative is currently dominating the headlines. Ireland’s position today is the same as a decade ago: both sides need to make sacrifices and swallow their pride for peace. This is exactly what the people of Ireland did in 1998, when they voted by an overwhelming majority to renounce any constitutional claim to Northern Ireland. Irish diplomats are fond of reminding their international counterparts of this moment.

The Irish public concurs: people across the political spectrum were revolted both by the images coming from Hamas’s terrorist attacks on October 7 and the images of children buried under rubble in Gaza. For decades, the nationalist and unionist communities on this island each claimed victim status; a rare silver lining of the Troubles is that the Irish now recognise that there is no hierarchy of suffering, and that targeting innocents is wrong no matter the cause. As a result, public opinion is behind the idea that a ceasefire is the only option in Gaza.

Lest we become too misty-eyed over Irish morality, it should also be noted that Ireland’s Jewish population is tiny — less than 3,000, a tenth of the UK’s Jewish population. Partly for this reason, the lobby in favour of Israel’s position is almost non-existent. There have been some prominent voices defending the nation’s actions over the past five weeks, most notably the former Minister for Justice Alan Shatter, a party colleague of Varadkar who compared pro-Palestinian marches to “the third Reich on the streets of Dublin”. He has also argued that because Ireland was a “bystander” during the Holocaust, it has no right to lecture Israel now.

Elsewhere, a handful of commentators have equated Irish criticism of Israel with antisemitism. For instance, a few months ago, another former Government Minister and pro-Israel campaigner Lucinda Creighton claimed that “it’s difficult to extract antisemitism from anti-Zionist and anti-Israel sentiment” in Ireland. And it’s true that, as in other European nations, some people in Ireland have been more intent on expressing their pro-Palestine credentials than condemning Hamas terrorism — with one group in Dublin proudly tearing down posters calling for the return of kidnapped Israelis. (That’s despite the fact that one of Hamas’s victims was an Irish citizen; the group is also believed to have abducted Emily Hand, the eight-year-old daughter of Irishman Tom Hand.)

But it’s worth emphasising that most of these unsavoury responses came from dissident republican or far-Left groups: to say they represent a tiny minority is an understatement. And contrary to some erroneous reporting, Hamas is officially designated a terrorist group by the Government. As a result, Irish officials refuse to even speak to the organisation.

Even so, Ireland still remains an outlier among Western nations in its strident criticism of Israeli militarism — and Netanyahu’s recent proposal for “tactical little pauses” to allow aid to reach Palestine is unlikely to change this. Only last week, Varadkar described his “enormous fears” that the violence will escalate. For if it does, Ireland’s already vulnerable relationship with Israel will likely be another casualty.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/