Imagine if Luigi Mangione had shot the CEO of a company that made light bulbs, or dishwashers, or breakfast cereal. Perhaps a few ideologues on Twitter would have hailed the killing as a justified strike against the one percent. But most people would have deplored it as a cold-blooded murder, or else ignored it entirely.

Yet America is openly applauding the assassination of United Healthcare CEO, Brian Thompson. A DJ at a Disney Channel-themed show in Boston last week played the song “He Could Be The One”, as the crowd erupted in cheers as Mangione’s mugshots were screened on the wall. Prisoners at the Pennsylvania facility where Mangione is incarcerated shouted “Free Luigi” and “Luigi’s conditions suck!” to a reporter outside. Tweets and posts glorifying Luigi abound, and what’s notably lacking from the conversation is any of the usual post facto discussion about gun control — this despite the fact he allegedly used an untraceable 3D-printed “ghost gun”. The takeaway is clear: many Americans are ready to support violent opposition to the health care system.

Mangione embodies a popular rage that has reached boiling point. This is not the rage of political extremists or ideological zealots; it is the rage of the normie. As an act of political communication, Mangione’s crime was remarkably effective. His purpose in killing Thompson was instantly obvious, and it was welcomed. Social media was flooded with tales of insurance woes — huge ambulance bills, coverage for crucial care denied. Though the problems in US healthcare are complex and not limited to the insurance companies, they are often the avatar of the system’s dysfunction. This is a country where the average family paid $23,968 for a private insurance plan in 2023, and 41% of adults have medical debt. The decisions of these distant, inscrutable corporate apparatchiks can have catastrophic consequences for patients.

There have been other signs that this frustration is reaching a tipping point. The rise of Robert F. Kennedy Jr, for example. Long written off as a crank for his opposition to vaccines, Kennedy’s long-shot presidential campaign resonated with a surprisingly large group of voters burned out by the Covid era. It garnered him enough influence to be tapped as Donald Trump’s nominee for health secretary. But the political class has ignored what it means that someone like RFK has gone mainstream, spending the election cycle focused elsewhere: Joe Biden’s age, wars abroad, Donald Trump’s legal troubles.

Healthcare affects Americans across party lines. But in Washington it is a partisan one, and sweeping changes to the system like the Affordable Care Act have been rare and hard-won. Now some politicians are talking about it again, including long-time healthcare crusader Bernie Sanders. “Finally after years, Sanders is winning this debate and we should be moving towards Medicare for All,” Rep. Ro Khanna, a Sanders ally, said last week. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, another progressive, came close to justifying Mangione’s action in an interview when she called it a “warning” that “if you push people hard enough, they… start to take matters into their own hands in ways that will ultimately be a threat to everyone”. But the response hasn’t been limited to the Left. The most powerful Right-leaning media figure in America, Joe Rogan, called the insurance industry a “dirty, dirty business” and “fucking gross” last week. Mangione’s action started to feel like — maybe, possibly — a catalyst for real change.

The question is whether or not the frenzy around Mangione can coalesce into some kind of sustained movement. He is already inspiring copycats, including Briana Boston, a 42-year-old Florida mother who was arrested last week for allegedly threatening Blue Cross Blue Shield after the health insurance company denied her claims. “Delay, deny, depose,” she is alleged to have said, echoing the words Mangione wrote on the shell casings of his bullets. “You people are next.” Meanwhile, the 2020 book from which Mangione borrowed the phrase, Jay Feinman’s Delay, Deny, Defend: Why Insurance Companies Don’t Pay Claims and What You Can Do About It, shot to second place on Amazon’s nonfiction bestseller list last week.

Mangione’s politics and worldview, though, aren’t easily categorisable. This has helped sustain his instant mythologisation as an Everyman hero. From his social media postings, he appears to be a political moderate with a heterodox worldview, interested in social science data and tech bro lifestyle content like Andrew Huberman. No one can really claim Mangione as an ideological ally, or dismiss him as an extremist. His Goodreads page ranges from the works of Jackass star Steve-O to the Unabomber’s manifesto.

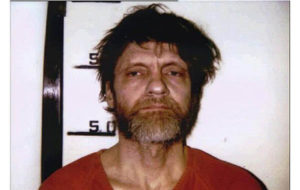

Though Ted Kaczynski is clearly Mangione’s closest parallel in modern times, the two provoked different public reactions. For Kaczynski, the dissemination of his manifesto was a major goal and his crimes were meant to call attention to it. But Kaczynski’s purpose — warning of the dangers of technological progress — was too abstract to resonate with Middle America, though he’s developed a loyal Gen Z cult following. By contrast, Mangione took direct action toward the representative of an easily understandable and widely hated target, in line with the “propaganda of the deed” ethos of turn-of-the-century anarchists such as the Italian militant activist Luigi Galleani. Kaczynski was a weird guy with a weird cause; Mangione is a (seemingly, so far) normal guy with a cause that is popular.

As with the Unabomber, violence has called attention to the perpetrator’s cause; unlike with the Unabomber, the public is more focused on supporting the cause than condemning the perpetrator. And this is what will trouble those in charge going forward: has an appetite for violent protest arisen among the average Joe? It’s not hard to glimpse a near future that harks back to the unstable political climate of the Seventies, marked by spurts of radical violence, or even further back to the roiling anarchism of the early 20th century, exemplified by the bombing campaign carried out by Galleani’s supporters in 1919 after his deportation. In 1925, Galleani wrote of the “individual act of rebellion” as “inseparable from propaganda, from the mental preparation which understands it, integrates it, leading to larger and more frequent repetitions through which collective insurrections flow into the social revolution”. These acts of rebellion, he thought, were necessary to spark a broader movement.

While being taken into a Pennsylvania courthouse for his extradition hearing last Tuesday, Mangione shouted to the cameras: “This is completely out of touch and an insult to the intelligence of the American people and their lived experience.” It’s this focus on “lived experience” in an area that so many Americans can relate to that has made Mangione into a martyr, and which could mark this moment as a political turning point. Mangione has managed to cut through layers of obfuscating discourse around healthcare, and he has proven that the issue has the potential to radicalise. The vast majority of Americans would not go to his extreme lengths. But his case will test whether the “propaganda of the deed” can change the currents of politics in the 21st century.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/