When Richard Nixon resigned as president 50 years ago, the country witnessed the birth of a monster. I am not talking about some sinister influence he exerted after his fall. I am talking about the media.

Having gratifyingly removed a leader who had become dangerous and unstable, the media, like a grizzly bear that kills its first human and will only eat human flesh from then on, shifted its purpose from investigate, report and expose, to search and destroy. In the process, it has normalised disaster thinking about American life, from the most ordinary experiences — love and work — to the highest echelons of human activity. If America is on the verge of political calamity, it is because for the past five decades, the media has kept the country on the edge of its seat expecting no less.

Unable to come up with another Watergate, the media tried to force every story it could into the Watergate template. Someone big had to be exposed as doing something really bad, with the result that they had to be made to fall exceptionally hard. There was some precious, honest, public-spirited journalistic work as a result. But the media, as befit its proud new image as heroic saviour of democracy, gradually robbed democracy of its vital essence: the freedom to live life privately, secretly, incalculably. (When Socrates said that “the unexamined life is not worth living”, he did not have in mind 24/7 cable news.)

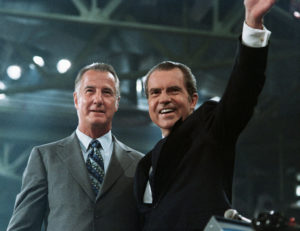

It was, of course, Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, in particular, whose doggedness exposed the connections between the Republican burglars of the Democratic National Headquarters and figures close to the paranoid, self-destructing Nixon. Their bestselling memoir, All the President’s Men, along with its blockbuster movie, made the men’s names synonymous with Watergate and media heroism. Never mind that had it not been for countless law enforcement figures, politicians and the Supreme Court, which ordered Nixon to give up the notorious tapes that incriminated him, Nixon might well have never been impeached. Woodward and Bernstein caught but the tip of the iceberg, yet it proved enough to keep the self-celebrating media’s champagne cold for two generations.

Like parents who refuse to allow their adult children to grow up, the liberal media has spent 50 years in a stage of arrested development. It continues to pretend that the country is a wayward child of the Sixties and Seventies, in need of the corrective hand of death-defying journalism. Indeed, the “woke” turn in the liberal media, now in the process of artfully incorporating criticisms of its pious effusions into its pious effusions, was really just an attempt to find a dramatically clear-cut moral issue, like Watergate, to get all heroic about, again. This desperation has been all the more intense since the media itself was discredited by its advocacy of the invasion of Iraq: having exposed the politicians as scoundrels, the credulous, war-mongering media got themselves indicted as same by the bloggers. Now, alternate universes of news on social media proclaim little Watergates every day.

In 2016, it was breath-taking to watch the media hurl itself at Trump in the hope of recapturing its pursuit of Nixon. It was hardly a coincidence that the movie The Post, about The Washington Post’s publication of the Pentagon Papers, came out just over a year after Trump was elected.

Yet the Nixon era seemed like innocence itself, as the epithet “Tricky Dick” mutated into “Hitler”, “Tiberius” and “Peron” as monikers for Trump. We longed for the bad old days, when the humble legwork of reporters like W and B, and sober, investigative columns by the likes of Jack Anderson, had not yet given way to the sniping, middle-school groupthink that too often passed for reporting after Trump’s ascent. In the Watergate era, the media exposed Nixon as a petty criminal. Now, in its longing to recapture its glorious past, the media has pummelled the petty criminal from Queens into a kind of Christ. Where Proust had his madeleine, nostalgic American journalism has its Trump.

Trump gave the “failing media”, as he calls it, a second life. But it was Nixon who elevated the media into a role that it had long hungered for: democracy’s indispensable eyes and ears. The invitation rang out among the protestors at the Chicago convention in 1968. “The whole world is watching” was an ironic slogan from a New Left that sought to deflate self-centred American arrogance. But the whole world cannot watch unless it has a medium to watch on. Enter TV news, and a new era of media domination.

Nixon himself, in his famous “Checkers” speech of 1952 — where he successfully debunked accusations of misusing campaign funds — made an end run around the dominant print media of the time by delivering his speech on television, just as Trump when he entered politics made an end run around TV and print journalism by resorting to Twitter. John F. Kennedy later used his photogenic charm to vanquish Nixon in the first televised debate in 1960, and TV news later helped serve as handmaiden to Nixon’s demise.

But the new media reality of constant vigilance and the pursuit of truth and justice had been established. Before Nixon, the news was just the news. There had been newspaper crusades; there was Edward R. Murrow’s truly heroic pursuit of Senator Joseph McCarthy. But the American press had never taken down a president. That was big game.

After Watergate, the press acquired a gravitational force usually possessed by sheerly political forms of power. It possessed a level of authority and reality all its own. Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel, the creators of the Superman comic strip, had known what they were doing when they made Superman’s alter ego a newspaperman named Clark Kent. They knew that the newspaper editors they were hoping to convince to publish their comic strip harboured their own alter egos as the Supermen who would protect the republic from harm.

Today, the media obsession with Nixon, sensationally lucrative and ego-gratifying, has mutated into a trillion-eyed media obsession with everything. The effect has been to turn democracy against itself. Here is Edward Shils in his classic work, The Torment of Secrecy, explaining why, “without the willingness to disregard much of what our fellow citizens do… there could be no freedom”:

“Democracy could not function if politics and the state of the social order were always on everyone’s mind. If most men, most of the time, regarded themselves as their brother-citizens’ keepers, freedom, which flourished in the indifference of privacy, would be abolished, and representative institutions would be inundated by the swirl of plebiscitary emotions — by aggressiveness, acclamation and alarm.”

Well, nowadays, most people, modelling themselves on the aggressive, acclimating and alarm-ringing media that Watergate created, regard themselves as just that. With Watergate, the American media established a style of never disregarding what our fellow citizens do, no matter how trivial or irrelevant. Of course, this has been taken up with fury by social media, where reducing the secrets of politics to everyday stuff is on everyone’s mind every minute, day and night. And once you declare secrecy an intolerable torment — the secrecy of the “deep state”, of hidden thoughts, of words and actions buried in the past — then any seeming exposure of truth has the liberating force of not being a secret. Exposing a secret has now become the sole criterion of truth. Even if it is a lie. Especially if it contradicts an official fact, which is by definition, something born in the realm of official secrets. Populism is thriving now not least because at the heart of populism is an abhorrence of secrets, which for some time has been at the heart of culture.

Unlike Trump, Ivy-educated, born to wealth, bathed in wealth, schooled and quickened in the sybaritic dens of sophisticated New York, Nixon was a born populist. Trump falsely believed that the 2020 election was stolen from him because he felt entitled to remain president; Nixon believed the Kennedys stole the election from him in 1960 because he felt humiliated by coastal elites all his life.

His pursuit of Alger Hiss for betraying American secrets to the Russians probably had as much to do with Hiss’s elite WASP background as with his treachery. Nixon’s eyes gleamed with satisfaction during his Checkers speech when he, accurately, accused Democrat presidential candidate, and mandarin of mandarins, Adlai Stevenson of misusing campaign funds. The root of Nixon’s populism was his feeling of smallness, of being an impostor always grabbing for more.

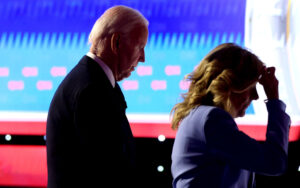

Yet this product of a world-historical inferiority complex established the Environmental Protection Agency, passed the Occupational Health and Safety Act, signed the Equal Rights Act into law, temporarily imposed wage and price controls, expanded the Food Stamp programme, and tried, unsuccessfully, to pass the Family Assistance Plan, which was an attempt at a guaranteed basic income that even Biden never pretended to espouse. He decreased troop levels in Vietnam, drastically reduced American casualties and extricated the country in 1974 from a war that had been created by liberal idealist opportunists, a war that had started with “military advisors’ in 1961. Even as he illegally expanded the war into Cambodia and Laos; even as he authorised Kissinger, long American high society’s favourite war criminal, to commit or enable atrocities in Cambodia, Chile, Bangladesh, Cyprus and East Timor; even as he tried to destroy his critics — he called them “enemies” — at home.

Nixon is routinely referred to as an enigma, a mystery, a cipher, a fungible opportunist. This is accurate, probably, but it is a tedious and tired narrative line that illuminates very little.

Fundamentally, Nixon was a watershed figure who led America away from any sort of shared reality into the obscure recesses of the American mind. That is to say, you couldn’t make sense of America during Nixon’s reign unless you turned away from the chaos in America and towards what made Nixon tick. That was when mind began to trump matter; when who a leader really was started to matter more than the context they acted in. That is another shift in the direction of populism. Populists prize personality, the more intriguing the better, in their leaders above all else.

After Nixon Aenigmaticus, the political question of our time is not: What does this person believe? No one, after all, believes anyone’s profession of belief anymore, least of all a politician’s. No, after Nixon, the question of our time, when it comes to democratic leaders, is not what, or who. It is when, and how, will a particular “who” begin to unravel. And, depending on your goals, or mere desires, what you can do to hasten it along. We are all our brother-citizens’ keepers now. We are all, that is to say, Woodward and Bernstein. Thanks to the self-anointed hero-journalists of yore, we are condemned to ceaseless, remorseless vigilance — all in the name of democracy.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/