In Baltimore the protests that followed the death of George Floyd felt less like an eruption and more like a mellow reprisal of events that had taken place five years earlier. The death of Freddie Gray in police custody had sparked protests that ended in injuries to both protestors and police, mass arrests, widespread property damage, arson, and no significant policy changes. The 2020 protests, in contrast, were less spontaneous, largely directed by civic leaders, and far less violent. Out of their ashes emerged a young mayoral candidate named Brandon Scott, who was running on a progressive platform of public safety.

As DEFUND BPD graffiti took over a prominent billboard on North Avenue, Scott was one of the few candidates who seemed in sync with the activist moment. He questioned the authorities’ over-reliance on police presence as they attempted to curb the violence plaguing the city. What Baltimore needed, he argued, was an expanded social safety net. But the darling of the activist Left would soon find himself at odds with his earliest supporters, as the reality of running a city with a spiking homicide rate became clear.

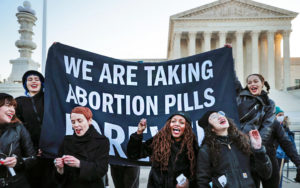

These tensions between activists and politicians were happening all across the country. Activists had been campaigning to end police violence for years when the death of George Floyd caught the world’s attention: finally, and abruptly, the words “defund the police” and “prison abolition” were appearing on the front page of the New York Times. Local politicians started running on issues such as bail reform. A handful of cities, from Philadelphia to Chicago to Seattle, all announced they were reallocating funds from bloated police budgets to other city services. Approximately $870 million was slashed from police departments nationwide. The idea was that with fewer police there would be more money to spend on the other services people want, which are typically underfunded. This in turn would boost the sense of community and stability — which should create a higher quality of life and theoretically bring down crime rates.

And then the homicide rate started to climb in cities across America. Many other crime statistics remained flat, but opponents to police reforms now had a frame for the backlash. Enthusiasm for slashing police budgets has faded — as has the idea that other services, such as housing, health, and drug rehabilitation programs, should be prioritised.

The debate is now absurdly binary: either you care about police violence, or you care about the homicide rate. Both these issues disproportionately affect the same demographics: economically vulnerable people living in under-serviced neighbourhoods are more likely to experience violence at the hands of both police and non-police. But anyone hoping to be an accepted member of either the Left or the Right must exaggerate one issue and erase the other.

Baltimore, a city plagued by poverty and violence, is a microcosm of what the defund debate has become. Brandon Scott’s main rival in the hotly contested 2020 mayoral race was former mayor Sheila Dixon. She started in the lead, despite the fact that she’d had to resign after being accused of stealing and using gift cards that had been donated to the city for distribution to needy families. One reason for her popularity, despite her alleged crimes, was her previous ability to bring the homicide rate to its lowest level in decades. Her success was mostly credited to “focused deterrence”, a strategy that includes police presence in high-risk communities and police intervention in the lives of high-risk individuals. Despite being effective and popular, this approach was mostly abandoned in the wake of Freddie Gray’s death, after anti-police sentiment had swept the city (the six officers involved were charged and their trials resulted in a mix of a mistrial, acquittals, and dropped charges; all officers returned to duty).

Still, it was Scott, who was city council president, who won out in the end. For years, he has approached gun violence as a public health crisis — one that requires sustained engagement from services beyond law enforcement. He has discussed the reallocation of resources to give other forms of intervention priority; activists interpreted this as support for the idea of defunding the police. And yet when he released his first city budget for approval, and the police budget remained around the same level as his predecessor’s, he was roundly condemned by critics on social media.

In response, Scott gave an interview in the Baltimore Sun, in which he criticised the “defund the police” slogan and its activists for focusing on the means rather than the ends. “We have to do a better job of explaining to folks what we’re talking about.” The goal should be a city in which every citizen is given the opportunity to flourish, and defunding the police doesn’t in itself achieve this. Moving numbers around on a budget is not policy; it is a symbolic gesture. And it’s a gesture that will only satisfy a small number of activists; a large percentage of residents would prefer the same or more police presence in their neighbourhoods. The majority support police reform over abolition.

Scott still believes in reallocating resources and ending the dependence the city has on police, but, he said in an interview with The Trace, “I need time.” He continued, “I have been consistent that reimagining public safety and the budget would not be overnight work.” But time is not something many activists have been willing to grant him. He has been in office for a year and a half, and has already become a target for those on the far-Left, who often point to this one budgetary marker as a sign of his failings rather than fairly assessing his policies. Scott’s first municipal budget increased funding for police to cover rising healthcare and pension costs. During the Taxpayers’ Night — an open forum for citizens to give feedback about how the city’s funds are being spent — multiple activists waited in line to express their anger and frustration with him. Many said they regretted voting for the young mayor.

When I moved from Baltimore to Philadelphia last year, I found a similar dynamic, with complicated realities obscured by the binaries, opportunism and bitter rivalries of local politics. Since the summer when 66,000 people marched in support of Black Lives Matter here, Philadelphia has been moving up the list of metropolises with the highest homicide rates in America. In 2019, it was fourteenth; now, it is twelfth. Last year, there were more murders here than in New York and Los Angeles.

Meanwhile, police shootings here have not made national headlines. Earlier this month police officer Edsual Mendoza was charged with murder. He shot 12-year-old Thomas Siderio in March. Between 2013 and 2021, 39 people, 26 of them black, were killed by the police.

Still, only a very small percentage of Philly’s population actually wants a decrease of police presence — including in neighbourhoods where police have killed or brutalised residents. They want services, such as affordable housing and free health clinics and public transportation and better schools, but they also say public safety is a top priority, and see police presence as a part of solving that problem.

Only 44% of Philadelphia residents feel “safe” in their neighbourhoods at night, and the largest percentage of residents who do are white. There is some truth to the criticism that the liberals who support defunding the police often don’t live in the neighbourhoods most afflicted by gun violence and homicides. And it doesn’t help that the most prominent professional activists in this arena, whether part of Black Lives Matter or the Women’s March, make headlines for lucrative book deals and expensive real estate purchases. The people on social media who most frequently and loudly talk about defunding the police often have extensive media bylines in their bios.

The city’s District Attorney, Larry Krasner, is adjacent to this demographic: a white civil rights attorney whose education from University of Chicago and Stanford has been brought up in a few of the conversations against him I’ve overheard. Krasner was elected in 2017, following widespread protests in Philadelphia against police violence — and the arrest of the previous DA Seth Williams on federal corruption charges. Krasner ran on a platform of ambitious reform, and he has delivered: his office has declined to prosecute low level prostitution or marijuana possession, and it is also implementing the controversial bail reform measures. Requiring cash for bail has for a long time left the poorest people in jail for weeks, months, and, in at least one high profile case, years, awaiting trial for nonviolent crimes. Krasner and other reformist DAs like him have pledged to put an end to this possibility, letting low-level offenders go home to wait for trial.

Krasner’s platform and unapologetic manner have brought him national attention, including an eight-part documentary series on PBS that gives an inside look at the work in his office and the controversies that have sprung from his tactics. Bail reform is an easy target for the Right: if someone with an extensive record commits a heinous act, a conservative will inevitably go on television to demand to know why that person was “on the streets” in the first place and not in prison. Locally, Krasner has been blamed for the increasing homicide rate, by both politicians and members of the police.

But like Scott in Baltimore, the most serious criticism that Krasner faces comes from his own side, the Left. In the mind of his most prominent critic, Michael Nutter, Krasner is a white saviour, thinking he knows best how to order the world while underserving the black people in neighbourhoods hardest hit by violence. The former mayor, who is black, said in an interview with the Washington Post: “It all goes back to supremacy, paternalism. ‘I’m woke. I’m paying attention. I spend a lot of time with Black people. Some of my best friends…’ All that bullshit.”

Nutter has referred in speeches to young black men as an “endangered species”, threatened by imprisonment, poverty, and violent death. He has long been an advocate for public safety, both before and after his eight years as mayor, and his term saw a significant decline in the Philadelphia homicide rate. Although there is no consensus about why or how that drop happened, but Nutter’s work, like Sheila Dixon’s in Baltimore, has often included a close relationship with the police, including controversial measures such as stop and frisk. As soon as Nutter left office, the white progressive Jim Kenney was elected as mayor and Krasner was elected DA, and those tactics were discontinued. And the homicide rate once again started to rise.

The most recent city budget presented by mayor Kenney significantly increased the funding for “anti-violence” programs, including neighbourhood organisations, after-school and summer programs, and workforce development programs — the same types of programs Defund the Police advocates have argued should take priority over policing. Philadelphia has also been slowly implementing other police-related reforms, such as a citizen oversight committee and the deployment of mental health professionals alongside police for certain emergency calls. Krasner enjoys widespread support from black voters, and his reforms have been largely popular in the city, despite the fact that a small handful of crimes have involved people who had been released on charges awaiting trial. But the effects of his work are not yet visible. The homicide rate for 2022 is already above what had been recorded by the same time last year.

The reality is that when crime rates go down, it’s hard to pinpoint a specific reason. Everything from neighbourhood development to the removal of lead paint from homes to robust police forces were credited with Philadelphia’s drop in violent crime in the Eighties. Similarly, when the homicide rate increased during the pandemic, many contradictory reasons were given. Gun sales had gone up — but was this cause, effect, or unrelated? Unemployment had gone up, but when it declined again it had no effect on the rate of violent crime. Were the police effectively on “strike”, refusing to engage in the prevention or intervention of dangerous situations because they were concerned about being blamed for bad results? Something similar had happened in Baltimore after the uprising that followed Freddie Gray’s death. But maybe other problems contributed too, such as rising rents or the difficulty of accessing health services during the pandemic.

The lack of clarity has allowed anyone, with any agenda, to speculate publicly about why homicide rates are climbing. For the head of the police union, it’s because the police force is underfunded and under-appreciated by the community. For conservatives, it’s because of broken families and lack of personal responsibility or because authorities are soft on criminals. For liberals, it’s the lack of gun control laws or poverty.

The truth lies somewhere in the middle, just as effective policy lies somewhere between anti-police activism and an unquestioningly pro-police stance. Crime rates aren’t predictable or easy to change, as local leaders across America are discovering. To pretend otherwise is to fail its victims.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com