One of the few things that has remained constant in 200,000 years of human history is our fascination with the female form: a source of desire, inspiration, even obsession. And the only thing more exciting than a woman’s naked body is a body that is not yet naked, or never entirely so, glimpsed bit by bit in a slow unveiling that stops short of sex itself. “The Daughter of Herodias”, a 19th-century poem by Arthur William Edgar O’Shaughnessy, rhapsodises about the dance of the Biblical character Salome, who titillates her male audience into a state of “mid ecstasy” by artfully showing only so much skin: “The veils fell round her like thin coiling mists … And out of them her jewelled body came.”

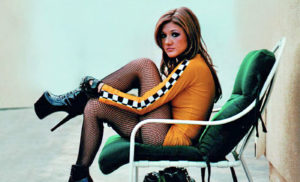

Today, the veils and jewels have been replaced by fishnet body stockings and six-inch lucite heels, but the intrigue surrounding strippers remains — as does society’s conflicted relationship with them. These women (and they’re almost always women) inspire a mess of competing sentiments: we pity them. We envy them. We want to help them and also just want them, sometimes at the same time. Against a modern-day backdrop of shifting sexual mores, strippers occupy the dual archetype of cautionary tale and aspirational figure, fallen woman and girlboss. They are the living embodiment of feminist agency, but also agents of the patriarchy. That the strippers themselves tend to disagree on all of the aforementioned points makes things even more complicated.

Meanwhile, the eternal fascination with sex-adjacent professions — strippers, phone sex operators, and, lately, the online purveyors of self-produced porn on OnlyFans — periodically coalesces into a pop cultural moment. The last one, in the mid-Nineties, gave us a glut of films including Showgirls, Striptease, Spike Lee’s Girl 6 — and, in an entertaining riff on the intersection of objectification and emasculation, The Full Monty. In keeping with the more purity-centric conventions of the time, these stories were mainly warnings: taking one’s clothes off for money was an inherently undignified enterprise, the purview of desperate women (or, in the case of The Full Monty, recently unemployed steel workers) faced with the choice to strip or starve.

Now, 30 years later, the wave of stripper content appears to be cresting again, this time in the form of multiple memoirs from current or former strippers, and this time without the implied subtext that these are the stories of fallen women. Genre-wise, the books run the gamut: Wanting You To Want Me, by Bronwen Parker-Rhodes and Emily Dinsdale, is a collection of first-person narratives and photographs from more than a dozen strippers, many still employed in the industry. The Ethical Stripper, by Stacey Clare, is a pro-sex-work, pro-labour argument steeped in the language and politics of contemporary social justice activism. Paulina Tenner’s Laid Bare: What the Business Leader Learnt From the Stripper is a run-of-the-mill business book dressed up in nipple tassels and a thong.

The only thing any of these titles have in common is a nominal (and in the case of Laid Bare, painfully contrived) connection to stripping. And yet, this loose mutual affiliation is also the most striking thing about them: that in our present moment, what used to be considered a dead-end job for desperate women might now also be a launchpad to greater things, at least for those with the means to make it so. Both Stacey Clare and Paulina Tenner are strip club veterans, now leveraging that experience to become thought leaders in activism and corporate strategy, respectively. Their credibility is burnished, not diminished, by their affiliation with what is still understood by many to be a seedy, exploitive industry.

It’s worth asking whether this credibility is deserved. For Tenner, the stripper connection feels desperately gimmicky — “In many ways company culture, no matter how evolved, is like a stripper’s arse,” reads one chapter opener — and only serves to highlight the relative dullness of the subject matter. (Despite the author’s best attempts to dress it up, the truth is that company culture is a great deal less interesting than a stripper’s rear end.) For Clare, the connection between the world of stripping and her central subject — the movement for sex workers’ rights — is both more organic and better executed. Her book artfully interweaves education with titillation, offering a detailed history of sex work activism in the UK alongside anecdotes from her own experience in strip clubs. That this narrative strategy in itself mirrors the push-pull of a striptease can’t be an accident: Clare clearly knows how to keep an audience’s attention.

And yet The Ethical Stripper is, in certain ways, even more tortured and grotesque than Laid Bare when it comes to massaging the truth. In service of its argument for fully legalised sex work, Clare dwells at length upon the labour issues inherent to stripping as a trade — including brutish club owners, exploitive business practices, and coercive customers — yet doesn’t engage with the potentially fraught nature of the work itself. In one anecdote about her experience with badly-behaved men at strip clubs, Clare writes of being “pretty much coerced” into a full-contact lap dance with a patron (in violation of the strip club’s cardinal “no touching” rule), yet her scorn is directed not at him but at the policies that constrained them both: “I consented because in truth I actually prefer giving full-contact dances, so it never feels like a violation, but I took a risk by breaking the rules of the club on my first night. It was a perfect example of how consent is undermined time after time by the economic context of the business model the industry is built on.”

Meanwhile, the notion that being paid to simulate sexual intimacy with strangers night after night might do something to a person is simply absent. And in lieu of reckoning with it, Clare tends to fall back on the rote identitarianism that has come to dominate so many progressive spaces. What might have been a compelling discussion of workers’ rights in an industry that is historically, and perhaps innately, hostile to women instead becomes a bunch of empty bluster about the importance of “the narrative”, the scourge of “whorephobia”, and the “appropriation” of “sex worker culture” by drive-by eroticists with (pun intended) no skin in the game.

It’s deeply strange to encounter this particular form of cultural gatekeeping amid what is supposed to be a conversation about worker’s rights: everyone from investigative journalists to Hollywood writers to practitioners of pole-dancing as a form of fitness are dinged for encroaching on stripping as if it were a protected identity category rather than what progressives insist it is: work. In an extended lament over the film Hustlers, Clare complains not only that its promotional events exploited strippers, but that the plot (based on a true story about NYC strippers who drugged their clients with MDMA and ketamine and then robbed them blind while they were passed out) would only create more stigma against sex workers.

But then, to focus at such length on offences given by a movie is a luxury in itself — which somewhat undermines Clare’s argument that strippers like herself represent an important faction within the larger category of marginalised persons known as sex workers. Publishing a book at all, let alone complaining within it that a Hollywood film failed to adequately represent your culture, implies a certain degree of privilege. But more than that, Clare fudges the lines between stripping and other, more dangerous forms of sex work in a way that feels a bit appropriative itself.

There is no better rejoinder to this approach than the collection, Wanting You To Want Me. The book features not only first-person narratives from a variety of different strippers who wouldn’t otherwise tell their own stories, but also this line, in the introduction, which captures the inherent tension of trying to roll up stripping and escorting and porn and prostitution into one big, sloppy sex work burrito: “[Strip clubs] are a form of escapism for everyone who enters, punters and strippers alike — an an enclave of desire and disappointment.” And yet, even in an environment steeped in sexual frisson, “the encounters that take place inside have very little to do with sex”.

Indeed, stripping is one of the few forms of sex work that not only leaves sex purely in the realm of unfulfilled fantasy, but in which the lack of satisfaction is the entire point of the thing. The men who frequent strip clubs are paying explicitly to be titillated, to be teased within an inch of their lives, and then to leave, without ever having touched the object of their desire. Why? What does this say about the men, about the nature of the transaction, about what is being really being sold when money changes hands in the Champagne Room?

And what are we to make of the fact that amid this glut of stripper-themed literature, only the women of Wanting You To Want Me — the ones who not only will never write a book but may never do any job apart from this one — are willing to dwell in the uncomfortable, unvarnished complexity of the work they do? There are no easy answers here, no unified narrative. But there is honesty: about how stripping can be a source of both shame and freedom at the same time, about the diversity of relationships that incubate within the confines of a strip club, about wanting to stop but also not wanting to, about the rapid-onset despair that comes when the fantasy can no longer sustain itself.

“Always at some point it happens that the balance tips and they want something that you can’t actually give them,” one seasoned stripper notes. “They realise that this make-believe isn’t actually gonna come true, and it becomes too sad or too pointless and hopeless.”

Of course, books like The Ethical Stripper cannot afford to be so honest. But perhaps this is the lesson: that the most compelling narrative, whether it belongs to a stripper or someone else, is one that does not seek to sell anything extra, be it a business strategy or a worthy cause. The most compelling story is just the truth: that stripping is hard, and fun, and sad, and exciting, and messy, and human, and it’s no surprise that 200,000 years later, we’re still writing songs about it.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com