“We’re born alone, we live alone, we die alone. Only through our love and friendship can we create the illusion for the moment that we’re not alone.” It’s a quote that bobs along the supposedly inspirational currents of the internet. In this case, what at first might appear a platitude is much wiser and darker than it seems.

The lines were added by Orson Welles to the script of what would be his final onscreen performance, Someone to Love (1987). The more one dwells on the quote, the more troubling it becomes. It does not belong in the realm of self-help. Instead, it is more akin to Joseph Conrad’s words in Heart of Darkness, “We live as we dream – alone”, words from a scene in which one character cannot convey to others the depths of his experience. He cannot reach them, and, in that moment, a terrible chill can be felt, a vertigo even, that perhaps we are all in the same position, or one day will be and the illusion will no longer hold.

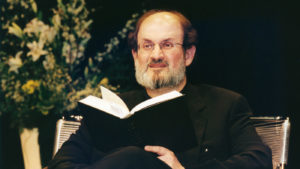

There are few moments where the solitary nature of life appears more inescapable than when one is clinging to it. The author Salman Rushdie lies recovering in an unknown location. His agent, Andrew Wylie, recently outlined the severity of the wounds Rushdie suffered after being attacked at the Chautauqua Institution in August. He has lost his sight in one eye and the use of one of his hands. He has “three serious wounds in his neck” and 15 in his chest. It is astonishing, if not miraculous, that he has survived.

Despite initial media activity around the attempt on his life, attention coursed on to “the next thing”. People seemed to assume that, once stabilised, Rushdie would quietly recover. Even in the presence of medical professionals and loved ones, Salman Rushdie is now, as he has always been, in this struggle alone. He alone will have to endure the aftermath. He has been doing so for decades.

The tendency to adopt him as a cipher for political interests has been lamentable. Rushdie is a fiction writer, albeit a remarkably curious and brave one. The Satanic Verses was rendered prophetic by the unfolding response and wider geopolitical contexts. The influence of the Ayatollahs was significant enough to warrant the author going into hiding, yet their reach had limits for as long as Western democracies held firm on protecting their citizens and enshrining rights, such as freedom of thought and speech, rights obtained through centuries of struggle and protest. Alas that was not the case.

When the fundamentalist Supreme Leader of Iran issued essentially a warrant for Salman Rushdie’s killing, and all who published him, it served as a colossal stress test of rights and protections in Western societies. In places, it began to buckle, with politicians, intellectuals and even fellow writers prevaricating, isolating and even condemning the writer for, in their minds, bringing murder upon himself. In a sense, Rushdie was doing what writers of note have always done — he was venturing out and testing, whether intentionally or not, how sturdy the ice was underfoot. As it turned out, it was more fragile than anyone had admitted, and soon cynics within the West would notice.

Looking back on the War on Terror and its human cost, it may be hard to conceive of the hostility experienced by those who spoke out against it. Millions protested and were effectively ignored. The seeds of an essentialism by which we are increasingly bound (“You are for us or against us”) took root. After the atrocities of September 11, emergency laws to restrict rights were introduced on a temporary basis — we were assured. Questions and debate, the basis of all scientific, philosophical and political enquiry and progress, provoked accusations of treason; we saw this, again, when questions arose over issues like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the origins of Covid-19 and so on. The seeds were planted when Rushdie was forced into hiding.

Writing and publishing may seem insignificant compared to the loss and mutilation of life that has transpired since the fatwa was declared against Rushdie. Yet the world of literature has some impact on the climate in which we all live, think and speak. Two damaging and interconnected developments have emerged — one very quiet and the other very loud.

Even while claiming to address political, social and cultural issues, the publishing industry (risk-averse at the best of times) has drifted more towards the uncontroversial, the orthodox and the solipsistic. With the exception of indie presses, which do much of the talent-spotting and grass roots development for the industry, and the occasional adventurous imprint, publishers have largely pursued a path of acquiescence, rendering themselves increasingly detached from a world that has more stories to tell, issues to face and places to explore than ever. There is certainly the illusion of controversy — the perpetual discovery of sex for instance, the wheeling out of straw men to attack or the time-travelling liberal interventionist attitude towards the complexities of the admittedly brutal historical past.

Periodically, articles will wonder why fewer and fewer people are reading. But little attention is paid to the echo-chamber of the industry and its remove from how most people actually live. What we can write, even speak of, as authors has, after a century of advancement, demonstrably narrowed. And the first gatekeepers, keeping inconvenient truths or contrary speculative fictions at bay, may well be our publishers.

It is difficult to transplant works from the past into the present day, given our present day has been partly shaped by those works but it is clear however that in terms of the impact it made, the bravery it took, and the freedom it assumed, there will not be another Satanic Verses. There may not be another Victor Hugo or a Nabokov. There may not be the equivalent of any of the books whose court victories broadened what it is we are able to publicly express, giving honest articulation to private thoughts — no Tropic of Cancer, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Ulysses. Puritanism now comes couched in the language of protection, which, in fact, was always part of the excuse for shutting down certain thoughts and marking certain lives as obscene. It was always a component of the political tool of erasure; we see this daily with reported bans on all manner of books from Ellison’s Invisible Man to Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale.

There is no denying the fear of crazed fanatics is real and understandable. Long before Rushdie was attacked, his Japanese translator, Hitoshi Igarashi, was stabbed to death, his Italian translator, Ettore Capriolo, was stabbed but survived, as did his Norwegian publisher, William Nygaard, who was shot in an assassination attempt. Thirty seven people died when a mob seeking to murder Rushdie’s Turkish translator, Aziz Mesin, set fire to the Madimak Hotel.

Naturally these crimes had a chilling effect. Yet there is something profoundly dispiriting to see an industry that was in the avant-garde for most of the 20th century volunteering to become its own censor. Some warned at the time, not least Rushdie’s loyal friend Christopher Hitchens, that submitting to theocratic fascists, the same ones that dissenting women are now courageously facing down in Iran, would only embolden and encourage them. After the Charlie Hebdo attacks, Rushdie was quoted in The Guardian, “Both John F. Kennedy and Nelson Mandela use the same three-word phrase which in my mind says it all, which is, ‘Freedom is indivisible. You can’t slice it up otherwise it ceases to be freedom.’” By seeking safety, the danger is that publishers have been moving increasingly towards irrelevance and vulnerability.

On the other hand, we have the noisy theatre of political engagement, especially on social media. This appears to be thriving until you realise how performative it is and how centred around the narcissism of small differences. Genuine unorthodox views are increasingly censored, and what it takes to be permanently suspended from Twitter or receive a call to your door from the police under disturbingly broad hate crime grounds appears ever-expanding. While there were notable cases of gloating online, the wave of sympathy for Rushdie was a sign that decency and empathy prevail. Yet, just as with the Je suis Charlie trend, some of the lamentations come from those who have pushed, even legislated, for restriction of speech; those who have applauded writers and academics losing their jobs or being no-platformed for the slightest deviation; those who have recreated an atmosphere of heresy that writers had, one day and not long ago, worked to dismantle.

Salman Rushdie was stabbed as he was about to give a speech, on America as a sanctuary for writers. In 1991, he gave a talk at Columbia University entitled “1,000 Days ‘Trapped Inside a Metaphor’”. In it, he tells us what is at stake, as a warning but also ultimately a statement of wonder, “I have learned the hard way that when you permit anyone else’s description of reality to supplant your own — and such descriptions have been raining down on me, from security advisers, governments, journalists, Archbishops, friends, enemies, mullahs — then you might as well be dead. Obviously, a rigid, blinkered, absolutist world view is the easiest to keep hold of, whereas the fluid, uncertain, metamorphic picture I’ve always carried about is rather more vulnerable. Yet I must cling with all my might to… my own soul; must hold on to its mischievous, iconoclastic, out-of-step clown-instincts, no matter how great the storm. And if that plunges me into contradiction and paradox, so be it; I’ve lived in that messy ocean all my life. I’ve fished in it for my art. This turbulent sea was the sea outside my bedroom window in Bombay. It is the sea by which I was born, and which I carry within me wherever I go.”

There will be pity now for Salman Rushdie, as there should be. And there should be support and solidarity for him. Yet what is also necessary is rage and shame that this obscenity was allowed to happen, and that Rushdie faced it ultimately alone, just as writers across the world do in the face of persecution and violence to callously indifferent silence. All of this, Rushdie, and his earlier treatment, warned of. Perhaps it could have been avoided if we all possessed Rushdie’s courage of convictions. Or perhaps safety in numbers is not always successful. Yet it is worth trying, not least because it helps to make the illusion that Welles spoke of more tangible. “Our love and friendship” are not meek passive things. They are a bond that requires courage and, on occasion in their defence, pain, integrity and risk.

Those who wished to shut down freedom of thought and speech have won to an extent but only with the assistance of those who claimed to be its advocates and guardians. If Salman Rushdie and what he is suffering means anything, that squalid victory must be reversed. It may be that Welles and Conrad were right and we are truly unreachable to each other — but, at the same time, we are not alone. For within us, we have as company, like the little cricket of Collodi’s Pinocchio, our conscience. Rushdie deserves, at the very least, rest. The rest of us have not yet earned that right.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/