When H. G. Wells imagined the end of the world, he thought of a salt dead sea under a dying sun. His time traveller, having navigated his machine 30 million years into the future, saw this: algal slime, lichenous rocks, a helpless, squid-like creature, moving fitfully in the blood-red water.

The Time Machine was published in 1895, and its image of the end times is shaped by the fears and discoveries of the late nineteenth century. The idea that evolution might slip into reverse, producing organisms fit only for the twilight. The idea that the earth was losing energy that it could not replace. “The time must come,” wrote Darwin’s great defender, T. H. Huxley, in 1888, “when evolution will mean adaptation to a universal winter, and all forms of life will die out, except such low and simple organisms as the diatom of the arctic and antarctic ice and the protococcus of the red snow.”

Today’s envisioned apocalypse is hotter. And sooner. Fire and flood and lots of it, the day after tomorrow. No need to set the dial to the distant future: we can see the glaciers melting. The intolerable world is one our grandchildren may know. How can we avoid this? Well, one way would be not to have any grandchildren.

Last month the Guardian published a mournful article about young men who have chosen to face the challenge of climate change by taking themselves down to the vasectomy clinic. Its principal interviewee, a 30-year-old council administrator from Essex, explained how he had come to the decision. “I thought: you know what? I don’t want to bring a life into this world, because it’s pretty shitty as it is and it’s only going to get worse.” The report made no grand claims about numbers, but he is not the first to identify the idea as a strengthening current.

In 2019, the journalist Wes Siler wrote about his decision to have the same operation for the same reason. “Is this a world we want to bring kids into?” he asked. In December 2021, Australian national radio carried an interview with a 24-year-old who had also chosen sterilisation as a way to reduce his impact on the environment. “I find it very frightening thinking about the way that the world is right now and what scientists are predicting the world will look like in 20 and 30 years,” said Aaron. “I didn’t think that was a great place to bring up a child.”

And last year, Dr Esgar Gaurin of Iowa, enthused by a service in Mexico City, put North America’s first mobile vasectomy van on the road. He chose Earth Day as his launch date, which he spent carrying out operations while parked outside the Holiday Inn Des Moines-Airport.

The vasectomy is now such an ordinary and unsensational birth control method that you’re as likely to hear about it in a comic context as any other. “Snip-snap, snip-snap, snip-snap,” says Steve Carrell’s character in The Office. “You have no idea the physical toll that three vasectomies have on a person.”

But 100 years ago, vasectomy discourse was very different. The operation was sought out by men who wanted to increase their impact on the world, not reduce it.

William Butler Yeats can serve as a starry example. In 1934, he complained to a friend that his creative and sexual energies were flagging. His friend, half-jokingly, recommended that he get “Steinached” — that is, have one of his two vasa deferentia cut and sealed.

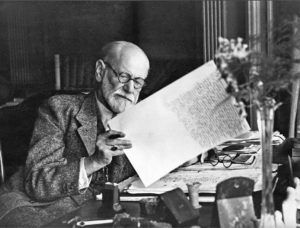

The procedure had been all the rage in Vienna the previous decade, after Eugen Steinach carried out his first operation on a middle-aged coachman who, 18 months later, claimed to feel like a much younger coachman. Sigmund Freud underwent it in the hope of keeping his mouth cancer at bay. Yeats read Rejuvenation (1924), the only English language book on the subject, and made an appointment to see its author, the Australian medic and sexologist Norman Haire.

Easy to imagine the scene in Haire’s six-storey Harley Street home, a riot of Chinoiserie and antiques with a bed “big enough for three,” according to Diana Wyndham (author of Norman Haire and the Study of Sex). The 68-year-old Yeats, under the silver ceiling of the top-floor consulting room, confessing that he is all out of poetic ideas, and that his erotic life is similarly moribund. Haire, boasting of the “rather less than 200” artists and intellectuals he has aided with his steady scalpel hand. Yeats rising from the table to enthuse, as he did to the poet Dorothy Wellesley, about “the strange second puberty the operation has given me, the ferment that has come upon my imagination.”

What was happening here? Not much, biologically, except the Placebo Effect. But stories like this are evidence of a strong impulse in early twentieth century culture to consider national (for which read white male) enfeeblement to be a problem with a medical solution.

In Arthur Conan Doyle’s story The Creeping Man (1923), for instance, Sherlock Holmes investigates the case of an academic exhibiting weird, aggressive behaviour. His “ape-like fury” turns out to be almost literal — a doctor in Prague has been supplying him with a serum derived from the black-faced langur, “the biggest and most human of climbing monkeys”. This wasn’t Doyle going off with the fairies. That same year, the Russian-born surgeon Serge Voronoff came to London to tell 700 fellow doctors that his monkey-gland grafts would revolutionise “male vitality”. (I don’t know whether the whole audience rose, but they certainly burst into applause.)

The idea took hold. So many rich, exhausted Jazz Age men wanted the op that Voronoff opened a monkey farm on the Italian Riviera. In July 1927, John Beckett, a rebellious Labour MP who later joined the British Union of Fascists, asked: “Could not a Voronoff gland be grafted on the English Government?”

It’s all pleasingly colourful and preposterous. At the level of social policy, however, we might be less inclined to snigger. Here, H. G. Wells comes back into the picture. Wells was a friend and supporter of Haire — Wyndham suspects he, too, may have been Steinached in Harley Street — and his work is shot through with his view of sterilisation as an instrument of eugenic reform.

His speculative essays Anticipations (1900) put it in the most extreme terms, suggesting that “the People of the Abyss” — those with transmissible diseases and disabilities — must be weeded from the population. “The nation that most resolutely picks over, educates, sterilizes, exports, or poisons its People of the Abyss,” he wrote, “will certainly be the ascendant or dominant nation before the year 2000.”

Wells’s position, if not uncontroversial, was entirely commonplace in early twentieth-century culture. When he was Home Secretary, Winston Churchill read a pamphlet by the vasectomy doctor H. C. Sharp called The Sterilisation of Degenerates (1910), and immediately began firing off questions to his officials. “What is the best surgical operation?” Churchill then wrote to H. H. Asquith, the Prime Minister:

“The unnatural and increasingly rapid growth of the Feeble-Minded and Insane classes, coupled as it is with a steady restriction among all the thrifty, energetic and superior stocks, constitutes a national and race danger which it is impossible to exaggerate.”

We don’t need to look too hard to find the echoes of these ideas in contemporary politics. They ring loudly in the Great Replacement theory — a white supremacist fantasy propagated by the far-Right French Presidential candidate Eric Zemmour and the glassy-eyed Fox News host Tucker Carlson — which suggests that white Europeans are being outbred by unacceptably fecund immigrant communities. Why are these men so fixated on the idea of flagging white virility? Why do they seem obsessed with the quality of Muslim sperm? Freud, alas, is not around to supply an answer.

But if he were, he might tell us that anxiety is a condition of modernity. And admit that, in his own case, a vasectomy turned out not to be a cure for what ailed him.

Every generation faces its existential terrors. Mine, which grew up in the 1980s, watched Protect and Survive films that advised us to put granny’s corpse in a bin bag, carefully labelled, if she died of radiation sickness. Having a vasectomy to save the planet isn’t quite as futile as having one to prevent a nuclear war, but it may come close.

The best we can say, I suspect, is that voluntary sterilisation is a fairly efficient mechanism to prevent a man from fathering another person who will be obliged to face whatever travails lie ahead of us. But an old story might worth taking into account here.

I heard it in a conversation between the US journalist Sigal Samuel and the climate scientist Kimberley Nicholas. It’s about Israelite men who abstained from sex because they didn’t want to create new slaves to Pharaoh. The women disagreed: their generation had failed, but perhaps the next would do better. So they seduced their husbands. Nine months later, Moses was born.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com