A recent court order requiring disclosure of the South African Covid-19 vaccine procurement contracts has caused a stir in social media and raised hopes that some of the secret clauses offering special protection to manufacturers might finally be revealed. The Romanian Member of the European Parliament Cristian Terhes, who has long criticized Ursula von der Leyen and the EU Commission for publishing heavily redacted versions of the EU’s own procurement contracts, hailed the ruling in a tweet as a ‘huge win for transparency & accountability,’ pointing, in particular, to the inclusion of the all-important ‘Pfizer’ contract among the documents to be released.

But why the excitement? The EU’s own procurement contract or Advanced Purchase Agreement (APA) with the consortium of Pfizer and the German company BioNTech has been available online in unredacted form for well over two years now: since, more precisely, April 2021, just shortly after vaccine rollout. It does indeed contain hair-raising clauses, which would undoubtedly have provoked massive opposition and ‘vaccine hesitancy’ had they been more widely known.

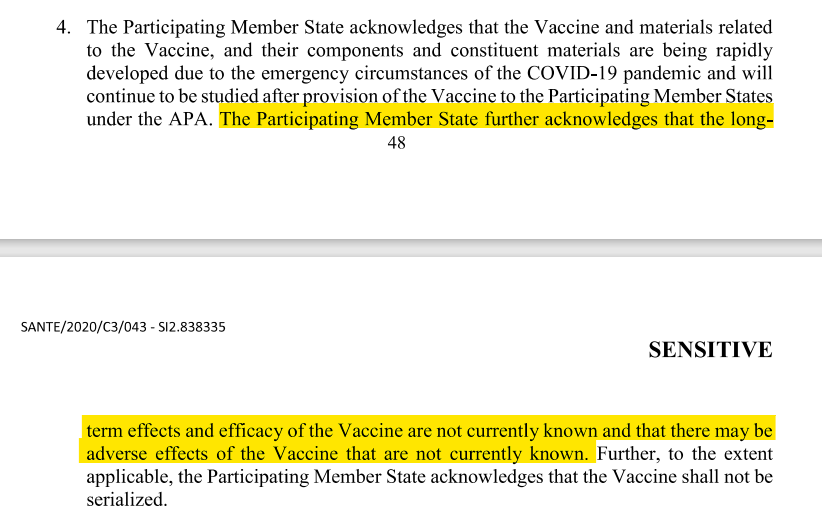

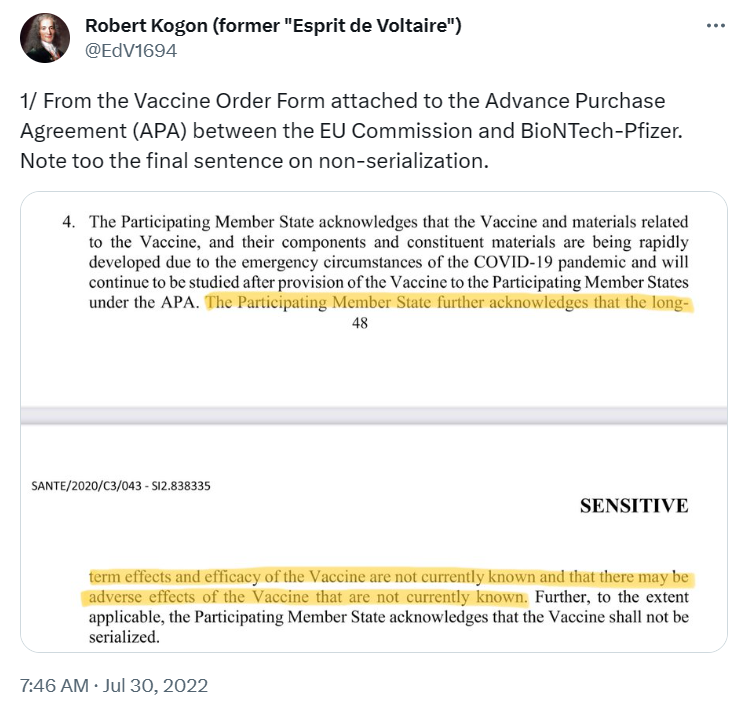

Consider, for instance, the following clause from Article 1, paragraph 4, of the Vaccine Order Form which is appended to the APA: ‘The Participating Member State further acknowledges that the long-term effects and efficacy of the Vaccine are not currently known and that there may be adverse effects of the Vaccine that are not currently known.’ (See full paragraph below.) How many Europeans would have rushed to take the vaccine or even consented to take it if they had known that?

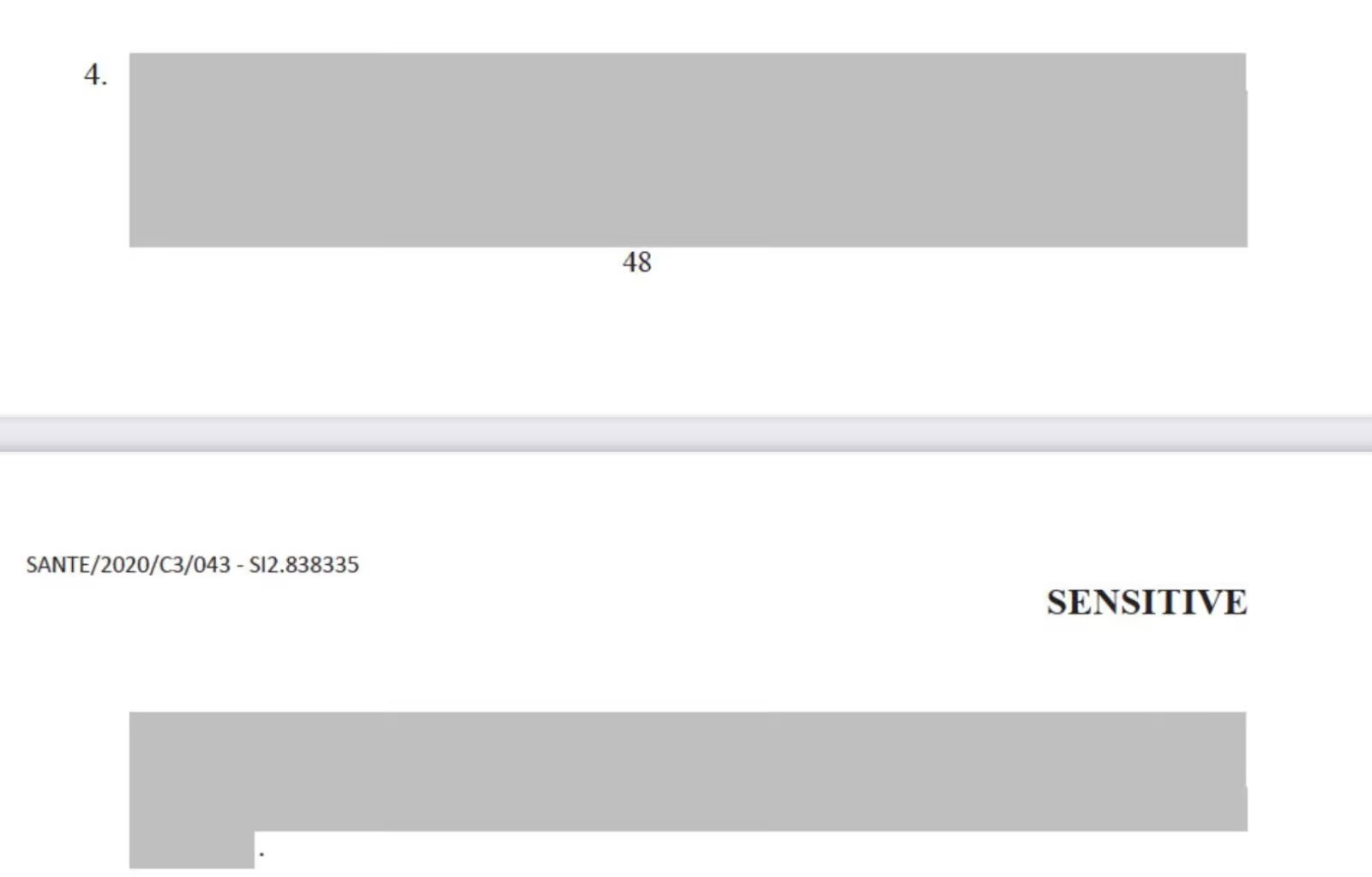

But they did not know it. For here is what the same paragraph looks like in the redacted version of the APA posted by the European Commission.

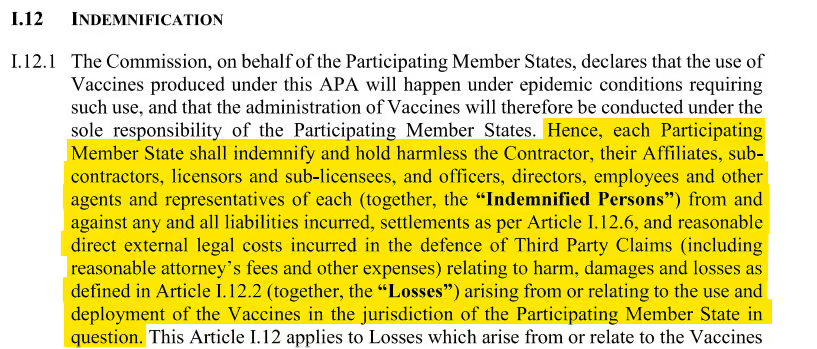

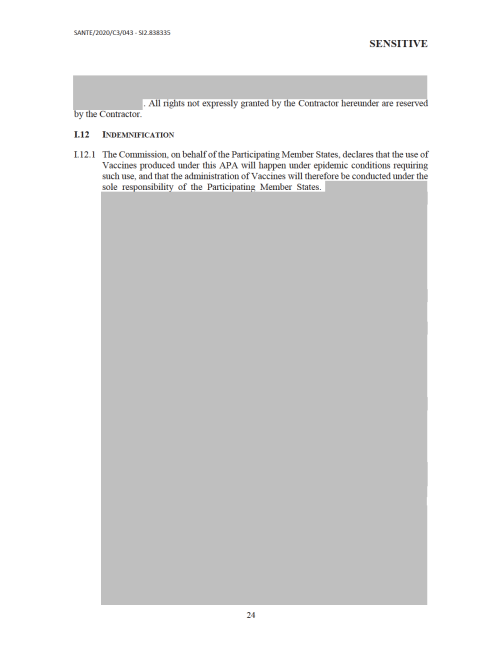

This ‘acknowledgement’ clause in the order form – acknowledgement, in effect, that the manufacturers knew neither if the vaccine was safe nor if it was effective, at any rate in the long term – is in addition to the clauses which already provide the manufacturers extremely wide-reaching indemnification in the section on indemnification of the contract proper. See, for instance, the excerpt from Article I.12.1 below.

The ‘contractor,’ as specified on the first page of the APA, refers to Pfizer and BioNTech collectively.

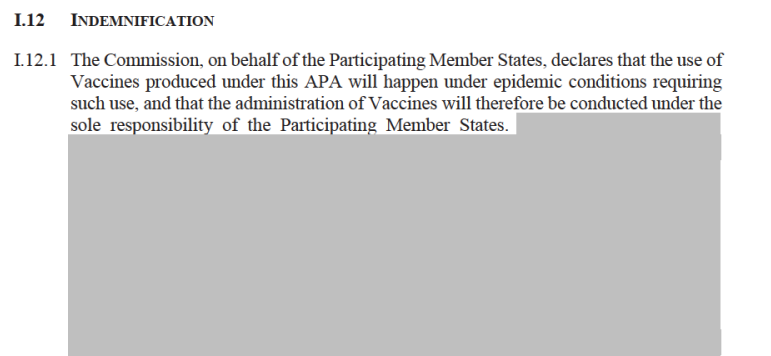

This is how the same passage looks in the redacted version of the contract posted by the European Commission.

Here is what the full page looks like.

And the following page.

In fact, apart from the first sentence, the entire section on indemnification, covering nearly three full pages of text, has been redacted in the version of the APA posted by the Commission. See pages 24-26 here.

It is these extensive redactions which have been the focus of Cristian Terhes and other vaccine-critical members of the European Parliament. Taking Ursula von der Leyen and the Commission to task for their lack of transparency, Terhes has made a regular practice of theatrically holding up blacked-out pages of the contract in plenary sessions. (See here, for instance, from October 2022.)

But if the unredacted version was available anyway, why did Terhes and his colleagues not also refer to that: i.e. to the actual content of the passages which were being hidden? And how did the unredacted APA and the obviously explosive provisions it contains fail to become better known?

Well, Cristian Terhes and the other MEPs will have to answer the former question themselves. If they were unaware of the availability of the unredacted document, they were made aware of it in September 2022: namely, by the present author in a tweet-reply to Cristian Terhes to which Terhes replied in turn.

But the answer to the latter question – why the existence of the unredacted APA has not become better known – is perhaps more intriguing and would appear to have something to do with the form of stealth censorship or ‘visibility filtering’ which has since become the norm precisely on Twitter.

Thus, in July 2022, after stumbling upon the unredacted contract, I posted a thread on it on Twitter, which quickly went somewhat viral by the standards of a small account, garnering hundreds of retweets and likes and eventually, according to Twitter’s own metrics, just over 100K impressions. I began the thread with the same acknowledgement of the unknown efficacy and safety of the vaccine highlighted above.

On September 11, 2022, I quoted this thread in the above-mentioned tweet-reply to Cristian Terhes and asked him why he was showing redacted copies of the EU contracts when the unredacted documents were available. Terhes’s response was to call into question the authenticity of the unredacted document. ‘Nobody can confirm that those unredacted versions are the real one,’ he wrote.

But the Pfizer-BioNTech contract was not just mysteriously floating around the web and it was not published by any obscure conspiracy website. It was published rather by the Italian public broadcaster RAI. The RAI is the Italian equivalent of the BBC.

The original April 17, 2021 RAI article, titled ‘Here Are the “Secret” Pfizer and Moderna Contracts for the Anti-Covid Vaccines,’ is available here. The article contains links to both the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna contracts.

The Pfizer-BioNTech contract has been available ever since on the RAI server here. (Beware that when I first tweeted the contract in July 2022, it temporarily became unavailable, perhaps because the resulting traffic was greater than the server could handle.)

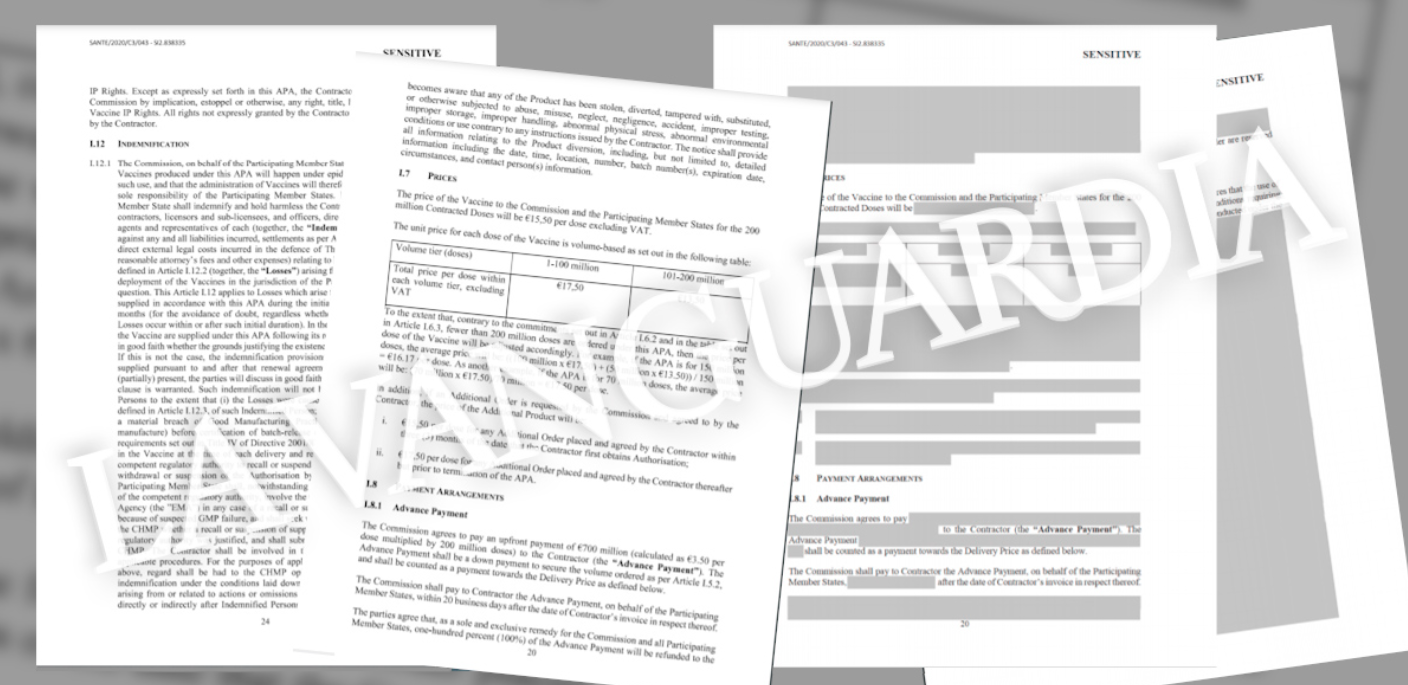

Furthermore, four days after publication of the RAI article, on April 21st, the Spanish daily La Vanguardia, Spain’s third largest newspaper in terms of readership, also announced that it had come into possession of the unredacted Pfizer-BioNTech contract – presumably simply by downloading it from the RAI website! – and published an article titled ‘The Contract With the European Commission Absolves Pfizer of Liability.’

Although, unlike the RAI, La Vanguardia did not post the contract as such, it did publish photos of selected pages, including a photo of the first page of the indemnification section I highlighted above, which it likewise contrasted to the redacted version published by the Commission.

On that same day, none other than Reuters also published an article on the leaked contract, citing La Vanguardia’s scoop (even though the scoop was in fact the RAI’s). Reuters, however, discreetly avoided mentioning the issue of indemnification, merely focusing on the price of the vaccine. (See ‘Leaked EU-Pfizer contract shows price for COVID vaccines set at 15.5 euros per dose’ here.)

So for three major European media, the RAI, La Vanguardia and Reuters, there was no question about the authenticity of the document when it first emerged in April 2021 – and before it again fell into oblivion. In the meanwhile, incidentally, Norman Fenton has also come upon the above-cited order form from the APA via a Slovenian FOI request, thus providing further confirmation of the document’s authenticity, supposing it were really needed.

But what was especially curious about my Twitter interaction with Cristian Terhes is what happened after it. Almost immediately after flagging the unredacted APA in reply to Cristian Terhes’s tweet, my Twitter account was hit with a shadow ban. This was what the results of my shadowban test looked like on the next day.

At the time, under the old Twitter regime, being shadow-banned was still a kind of status, which could be easily and accurately verified by online shadow-ban tests (or even by users themselves by searching for their own tweets when logged out of their accounts).

Furthermore, some other Twitter users let me know that they were unable to like or retweet my reply. See below, for instance. Similar feedback in the same vein is no longer available since Twitter has permanently suspended the author’s account.

This was not all that unusual per se. It will be recalled that tweets labelled ‘misleading’ under the old regime could not be liked or retweeted. But what was ‘misleading’ about my tweet? And, more to the point, it was precisely not labelled as such. Nonetheless, it appeared – surreptitiously – to be subject to similar sorts of restrictions.

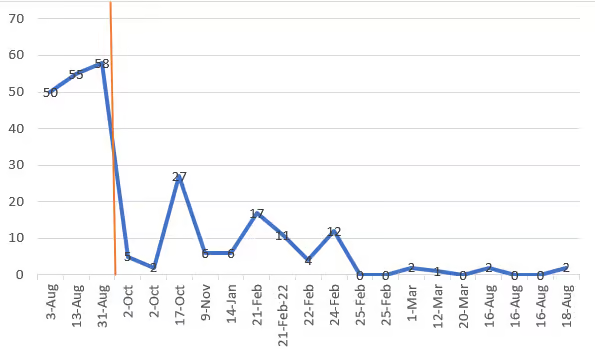

Thereafter, engagement with my reply-tweets quoting the thread plummeted in general, occasionally popping up again, but still to less than half the previous level, before trending down to essentially, and apparently permanently, non-existent under the new Twitter regime. The below graph of relevant engagement (likes + retweets) before and after the date of the interaction with Terhes illustrates this. It only includes tweets in which I used the word ‘unredacted.’

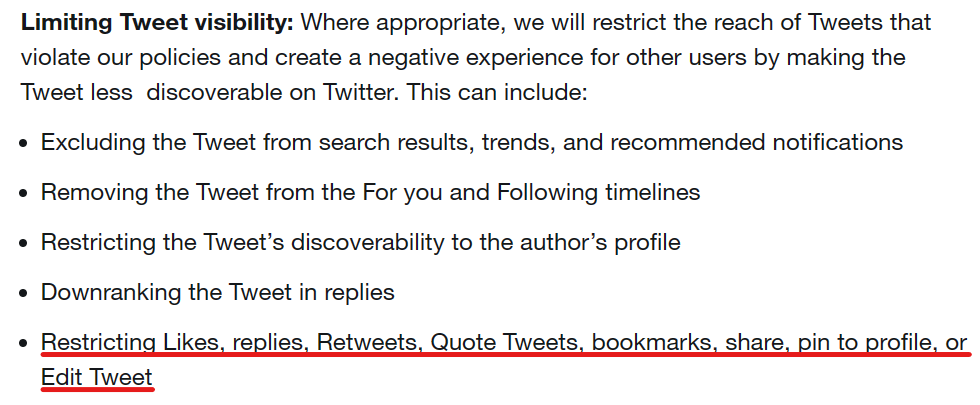

Restricting engagement remains very much a thing on the new Twitter/’X,’ as ‘X’ CEO Linda Yaccarino readily admits and as can be seen in the below extract on ‘Tweet-level enforcement’ from the X ‘Help Center.’ Indeed, the actions taken to suppress tweet visibility appear to be more extensive now than under the old regime. (‘Misleading’ tweets could be quoted, for instance.)

But unlike the old Twitter, which as a rule let users know when action was being taken against a given tweet, ‘X’ no longer publicizes the fact.

Interestingly, the ‘Help Center’ also acknowledges that such action may be taken in response to a ‘valid legal request from an authorized entity in a given country.’ Who knows what a ‘valid legal request’ is. But presumably the European Commission would count as such an ‘authorized entity’ – especially since the Commission is designated as the ultimate regulator of online speech under the EU’s Digital Services Act. (See, for instance, here, here and here.)

In any case, the party with the most obvious interest in suppressing the unredacted APA is, of course, the party that redacted the document in the first place: the European Commission. It is not hard to imagine why the Commission would want, so to say, to ‘re-hide’ it.

Did old Twitter restrict the visibility of the unredacted APA in response to a request from EU authorities? Is new Twitter/’X’ continuing to do so today?

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: Brownstone Institute Read the original article here: https://brownstone.org/