Metaphors And Historical Understanding

There is no such thing as fully objective history, and that’s for a simple reason. History is generated in narrative form, and the creation of every narrative—as Hayden White made clear four decades ago—necessarily involves the selection and discarding, as well the foregrounding and relative camouflaging, of items within the panoply of “facts” at the disposal of the historian.

Moreover, when it comes to constructing these narratives, all who chronicle the past are, whether they are aware of it or not, limited to a great extent by the repertoire of verbal cliches and conceptual metaphors that have been bequeathed to them by the elite institutions of the cultural system in which they live and work.

I was reminded of this reality, and its often quite detrimental effects on the conduct of policy-making, while watching the extremely informative interview Tucker Carlson recently did with Jeffrey Sachs.

In it, the globe-trotting economist and policy advisor generates what is, I suspect for most Americans, a completely different version of what has taken place over the last thirty years on the level of US relations with Russia. He does so by refuting the customary cliches and conceptual presumptions of mainstream US versions of this history one-by-one and in great detail.

He suggests, in sum, that the Western journalism and policy-making classes (Is there a distinction today?) are so immersed in their own repertoire of culturally-bound discursive commonplaces that they are incapable of seeing, and therefore grappling with, the realities of today’s Russia in any halfway accurate fashion, a perceptual disconnect, he adds with alarm, that could lead to funereal outcomes.

While his analysis was very sobering, it was nonetheless heartening to listen to an establishment insider with the ability to recognize his country’s dominant and self-limiting critical paradigm in regard to Russia and to share possible other ways of framing these crucial matters in new and possibly more accurate ways.

As refreshing as this all was, the interviewer and his guest nonetheless fell into one extremely resistant cultural cliché when the conversation turned to the matter of previous empires and their geopolitical behavior.

Carlson: But the pattern is recognizable immediately. Here you have a country with unchallenged, for a moment, unchallenged power, starting wars for not any obvious reason, all over the world. When was the last time an empire did that?

At this point Sachs takes an approach I’ve come to expect from even the most well-educated Americans and Brits when the subject arises: he speaks a little bit about the possible parallels with the British Empire and the Roman Empire.

And that’s it.

That Other Great Empire

What Anglo-Saxon analysts almost never do is to seek lessons in the trajectory of an empire that lasted from 1492 until 1898 and that was, moreover, in quite intimate contact with first Great Britain, and then the US during its 394-year history.

I am, of course, referring to Spain. Insofar as the subject is broached at all, it is in relation to the Iberian nation’s role in conquering and settling what we now refer to as Latin America.

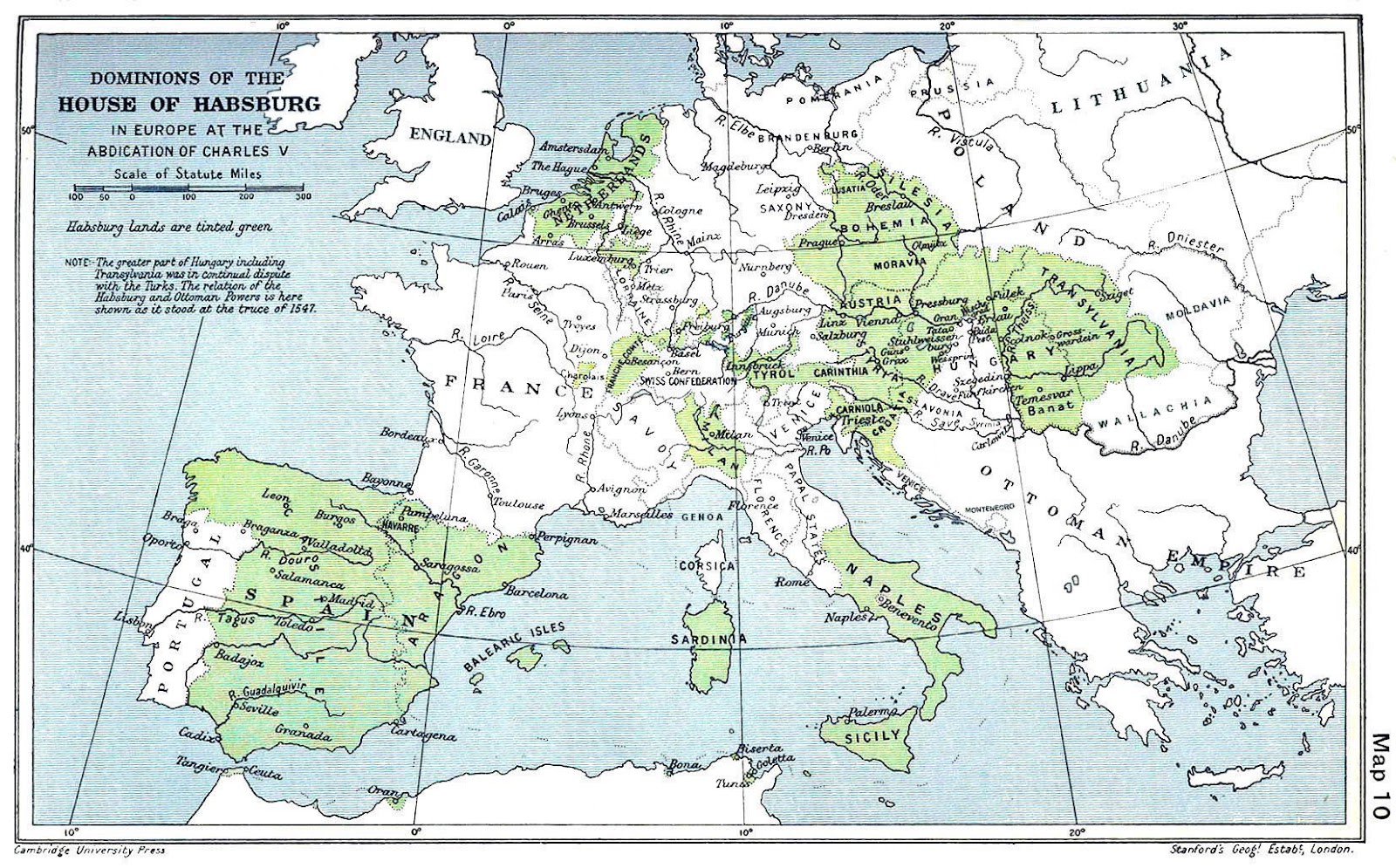

That’s fine, good, and necessary. But it tends to obscure the fact that in the period between 1492 and 1588, Spain was by far the most important economic, military, and cultural power in Europe with the Spanish crown exercising de facto territorial control over all of the Iberian peninsula besides Portugal, much of today’s Italy, all of today’s Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg, parts of France, and at least until 1556, much of today’s Austria, Czechia, Slovakia, and Slovenia and parts of today’s Croatia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania. All this, of course, in addition to its vast American colonies.

Perhaps as important as this enormous access to people and resources was Spain’s outsized influence within the closest thing that 16th century Europe had to transnational organizations like today’s UN, World Bank, and NATO: the Roman Catholic Church.

Through an intricate system of revenue sharing, donations, and bribery backed by strategic campaigns of military intimidation, Spain, much like today’s US in relation to aforementioned transnational institutions, gained a large-scale ability to employ the wealth and prestige of the Church of Rome as an adjunct to its imperial designs.

Pretty impressive. No?

Which, of course, brings us back to the question Tucker Carlson issued to Sachs.

Here you have a country with unchallenged, for a moment, unchallenged power, starting wars for not any obvious reason, all over the world. When was the last time an empire did that?

The answer, of course, is Spain. And the picture of what those wars, and the often unidimensional thinking upon which they were based, did relatively quickly to that country of once vast and essentially unchallenged power, is not pretty.

And I believe that if more Americans took the time to learn about Imperial Spain’s historical trajectory they might be a bit more skeptical when it comes to cheering, or even silently assenting to, the policies being pursued by the current regime in Washington.

Empire as a Continuation of Frontier Culture

It has often been postulated that the US turn to empire was, in many ways, an extension of Manifest Destiny, the belief that the Almighty had, in his wisdom, foreordained that Europeans would wrest control of the North American continent from its native inhabitants and build upon it a new and more righteous society, and with that job essentially done, it was now our task to “share” our providential way of running societies with the world.

This outlook is bolstered when we consider that, according to the famous dictum of Frederick Jackson Turner, the US frontier closed in 1893, and that, according to most scholars, the era of overt US imperialism began 5 years later with the seizure through a brief offensive war of Spain’s last remaining overseas colonies: Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines.

The Spanish empire was born out of a similar dynamic.

In 711 AD, Muslim invaders crossed the Straits of Gibraltar into Europe and took de facto control of the Iberian peninsula in an extraordinarily short time. According to legend, the Christians made their first substantial counterattack in 720. Over the next seven centuries, the Iberian Christians endeavored, in a process referred to as the Reconquest, to cleanse the Peninsula of all Muslim influence, generating a fierce martial culture and a war-based economy in the process.

In January of 1492, this long warring process came to its end with the fall of the peninsula’s last Muslim outpost, Granada. And it was precisely in the fall of that same year that Columbus “discovered” America and claimed its vast riches for the Spanish crown.

Over the next half-century, the warring spirit and martial techniques honed during the long struggle against Islam, undergirded by a deep belief in the God-given nature of their mission, fueled a truly remarkable, albeit also deeply violent, takeover of much of the Americas south of today’s Oklahoma.

A Meteoric Ascent to Prominence in Europe

One of the remarkable things about the US is just how swiftly it was transformed from an essentially inward looking Republic in say 1895, to world-striding empire in 1945.

The same could be said about Spain. Castile, which was to become both the geographical and ideological center of the Spanish empire, was in the middle decades of the 15th century a largely agrarian kingdom racked by civil and religious wars. However, with the marriage in 1469 of Isabella, the heir to the Castilian throne, to Ferdinand, the heir to the Aragonese crown, the two largest and most powerful kingdoms of the Peninsula came together, establishing through their union the basic territorial outlines of the state we today refer to as Spain.

Though each kingdom would retain its own legal and linguistic traditions until 1714, they would often (but not always) cooperate in the realm of foreign policy. The most important upshot of this policy of ad hoc cooperation in relation to the world was that the more inward-looking Castile was brought into much greater contact with the Mediterranean world where Aragon, had, starting in the 13th century, forged a very impressive commercial empire rooted in the control of a number of European and North African ports.

The next leap forward in terms of Spain’s influence in Europe took place when Ferdinand and Isabella married their daughter Juan “La Loca” off to Philip the Fair of Habsburg. Though neither the Dutch-speaking Philip nor Juana (because of her alleged mental illness) would sit on the Spanish throne, their sons (Charles I of Spain and Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire) would. And when he did, starting in 1516, he did so as the sovereign of all the Spanish territories in America and virtually all of the European territories shown in the map above.

Spain and the Custodianship of its Newfound Wealth

While it is true that great power often invites great insurgencies, it is also true that tempered and judicious use of power can blunt or even reverse many such attempts of lesser entities to take it, as it were, to the imperial “man.”

So how did Spain manage its newfound wealth and geopolitical power?

When it came to managing its wealth, Spain arrived at the status of the Western world’s greatest power with a distinct disadvantage. As part of its campaign to drive the Islamic “infidels” from the Peninsula, it had also sought to rid the society of its Jews, who had formed the backbone of its financial and banking class.

While some Jews converted to Christianity and stayed, many more left for places like Antwerp and Amsterdam where they flourished, and were later instrumental to the ability of the Low Countries (today’s Belgium and Netherlands) to subsequently wage a successful war of liberation against Spain.

The Spanish monarchy would double down on this morally and tactically dubious policy 117 years later, in 1608, when it was decreed that all those subjects descended from Jews and Muslims (the backbone of the technical and artisanal classes in many areas of the country) who had converted to Christianity in order to stay in 1492 would have to also leave the country. Thanks to this second expulsion of supposed Crypto-Jews and Crypto-Muslims from the Peninsula another of Spain’s great rivals, the Ottoman Empire, gained untold amounts of wealth and human capital.

I could go on. But there is a strong consensus among historians that Spain, led by Castile, largely mismanaged the enormous wealth that flowed into its coffers from its plunder of America and its control of very wealthy territories of Europe, the most salient proof of this being its failure, outside of a few geographical pockets, to developing anything resembling a sustainable approach to generating and sustaining societal wealth.

But perhaps even more important than the Spanish Empire’s obtuseness in things connected to financial management was its penchant for waging costly and often counterproductive wars.

Spain as the Hammer of Heretics

It was mere months into Charles’s reign (1516-1556) as king of Spain and Habsburg emperor that Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the wall of his church in Wittenberg, in the northern part of today’s Germany. As Spain’s power in Europe was intimately linked to that exercised by the papacy in Rome, Luther’s strong critique of Catholic doctrine instantly became a matter of geopolitical concern for Charles, so much so that in 1521 he traveled to Worms in the Upper Rhine region to confront the dissident priest and declare him a heretic.

This decision to recur to blunt punitive force in the face of critiques that, as subsequent events would prove, were viewed with sympathy in many parts of his realm, would spark a series of religious wars in northern and central Europe as well as France over the next century and a third, with Charles and his successor generally aiding the Catholic participants in all of these conflicts with money and/or troops.

The most costly of these wars for Spain was the Eighty Years War (1566-1648) against Protestant rebels in the Low Countries, a traditional Habsburg holding. This religious conflict proved enormously costly, and like most of the others was, in the end, resolved not to the benefit of Catholic forces but rather the Protestant insurgents.

Spain and the Counter-Reformation

The ultimately ill-fated Spanish-led drive to retain Catholic supremacy in Europe under Charles and his son and successor Phillip II also had profound cultural consequences.

Today when we think of the Baroque, we think of it mostly in aesthetic terms. And that is certainly a licit way of looking at it. But it tends to obscure the fact that the Baroque was intimately linked to the Counter-Reformation, an ideological movement designed by the papacy in coordination with Spain to ensure that fewer members of the Church of Rome be attracted to the various emergent strains of Protestantism which, with their emphasis on the pro-active task of seeking to understand God and his designs through individual scriptural analysis (as opposed to doing so through the passive assimilation of clerical edicts) was attracting many of the Old Continent’s brightest minds.

Aware that they could not compete with the emergent Protestant sects on the level of pure intellectuality, the architects of the Counter-Reformation placed the sensual, in all its forms (music, painting, pictorial art, architecture, and music) at the center of religious practice. The result was the collective aesthetic treasure we call the Baroque, which, as paradoxical as it may seem, was driven by a desire to disable the “dangerous” rational and anti-authoritarian spirit (in relative terms) of Protestantism.

Battles with France for Supremacy in Italy

The first Iberian attempts to conquer territory in Italy date to the Aragonese conquest of Sicily at the end of the 13th century. This was followed in the 14th century by the conquest of Sardinia. In 1504 Aragon, now linked to Castile, captured the enormous Kingdom of Naples, giving the Spanish crown control of virtually all of Southern Italy. In 1530, the Spanish crown took control of the wealthy and strategically located—it was the gateway for sending troops northward from the Mediterranean Sea toward the religious conflicts in Germany and subsequently in the Low Countries—Duchy of Milan. This last conquest was extremely expensive as it was the result of a long series of conflicts during the first third of the 16th century with a fast-rising France and the still very powerful Venetian republic.

And perhaps most important was the enormous cost of maintaining control of these valuable territories through massive troop deployments.

Spain and the Ottoman Empire

And all this was going on at the same time as Charles’ contemporary Suleiman the Magnificent was transforming the Ottoman Empire into a military and naval power at the other end of the Mediterranean. He first attacked the Habsburgs in Hungary and Austria, setting siege to Vienna in 1529. While the attack on Vienna was eventually repelled by the Habsburgs, the Ottomans retained effective control of Hungary. The Balkans in general and Hungary in particular would remain a site of constant Habsburg-Ottoman battles over the next two decades.

At the same time, Suleiman was establishing control of much of the northern African coast, long an area of Aragonese commercial interest. So, in 1535 Charles (in person) sailed off with 30,000 troops to wrest Tunis from the Ottomans. Over the next 35 years, Catholic forces led, and largely paid for by the Spanish crown, clashed repeatedly in huge and brutal battles with the Ottomans in the Mediterranean (e.g. Rhodes, Malta) on the belief that doing so would assure Spanish and Christian control of that key basin of commerce and cultural exchange.

This long set of conflicts culminated with a Spanish victory at Lepanto (Nafpaktos in today’s Greece) in October of 1571 which definitively stopped the Ottoman Empire’s attempts to extend its control over shipping lanes into the Western Mediterranean.

Spain’s Unipolar Moment

Like the US in 1991, Spain in 1571 stood, or so it seemed, unrivaled in terms of its control of Western Europe, and of course, its incredibly large and lucrative colonial dominions in America.

But not all was what it appeared to be. The religious conflicts within the Habsburg realms were, for all of Spain and the Church’s attempts to disappear them through the force of arms and Counter-Reformation propaganda, burning more intensely than ever in the Low Countries.

And, as so often happens to established powers when engaged in wars to preserve their hegemony, they become so immersed in their own rhetoric of benevolence and superiority (the two discourses always go together in imperial projects), that they lose their ability to accurately gauge the essential nature of their enemies, or perceive the ways in which those same enemies may have overtaken them in key areas of social or technical prowess.

For example, whereas Spain, as we have seen, was exceedingly slow to develop a banking structure capable of promoting capital accumulation, and hence the development of anything approaching modern commercial and industrial development, the more Protestant-dominated areas of the continent forged ahead in these areas.

Did the Spanish imperial authorities take note of these key economic developments? Generally speaking, they did not, as they were confident the religiously-infused warrior culture that they saw as having delivered them to world prominence would cancel out the benefits of this more dynamic way of organizing the economy.

By the latter half of the sixteenth century Spain’s obtuseness in this key area was evident. It was receiving more precious metals than ever from its American colonies. But because the country had little or no ability to produce finished goods, the gold and silver left the country almost as quickly as it flowed in. And where did it go? To places like London, Amsterdam, and heavily Huguenot cities of France like Rouen where both banking and manufacture were flourishing.

And as the gold inflows from America decreased (thanks, among other reasons, to state-sponsored British piracy) and the number of Spain’s armed conflicts continued to increase, the empire was forced to seek outside funding. Where did they go to get it? You guessed it. To the bank in the very same enemy cities of northern Europe whose accounts they had fattened through the purchase of manufactured goods. By the end of the third quarter of the 16th century, huge deficits and huge government interest payments were an intractable element of Spanish governance.

In the words of Carlos Fuentes:

“Imperial Spain abounded in ironies. The staunchly Catholic Monarchy ended by unwittingly financing its Protestant enemies. Spain capitalized Europe while decapitalizing itself. Louis XIV of France put it most succinctly: ‘Let us now sell manufactured goods to the Spaniards and receive from them gold and silver.’ Spain was poor because Spain was rich.”

To which I might add, Spain was militarily vulnerable because Spain was militarily omnipotent.

Into the Land of Magical Thinking

As mentioned above, a now-Protestant and ever more militarily imposing England began, in the middle years of the 16th century, to use piracy as a tool for both stealing gold and thwarting heretofore unchallenged Spanish control of Atlantic trade routes. Needless to say, this bothered Spain, as did England’s penchant for supporting the Protestant rebels in nearby Holland.

At this point, however, Phillip II might have considered the possibility that his unipolar moment had ended much more abruptly than he had hoped and that he might need to alter his ways of dealing with his geopolitical rivals.

He decided, instead, that it would be smarter to try and inflict a massive blow against England that would knock it out of the realm of great power competitions, and perhaps even the club of insurgent Protestant nations, forever and ever, Amen. The tool for doing so would be a vast naval expeditionary force, known to most today as the Grand Armada.

The enormously costly effort to rid Spain of the British threat once and for all was led by a political crony who had never been to sea and was rife with corruption from the start. Moreover, the effort had no clear strategic endpoint or goal. Would it end with the full surrender of England under Spanish occupation, the mere blocking of its trade routes, or the destruction of its naval and merchant fleets? No one actually knew.

As it turned out, the Spanish never got close to having to deal with their own lack of strategic clarity. Arriving at the English Channel in search of their first encounter with the British in the summer of 1588, they soon discovered that many of the 120-odd ships (several had been lost on the trip up from Spain) assembled for the effort were quite leaky and ill-assembled, slower than the British ones and, design-wise, completely unsuited for maneuverability in the much rougher waters in the Channel.

As the Spanish approached English waters the much smaller English fleet with much less firepower sailed out to greet them. In the maneuvers to evade them the Spanish fleet fell into chaos, provoking collisions between friendly ships.

The English took advantage of the chaos and captured a key Spanish galleon. This was just the beginning of a long series of logistical disasters for the Spanish, topped off by the rising of a strong gale that further disrupted Spanish formations and sent their ships drifting away from the intended sites of conflict.

Barely two weeks after the beginning of their bold attempt to rid the world of the British menace “once and for all,” it was clear that Spain had lost. Following the prevailing winds, the remaining ships sailed northward, and after circumnavigating the upper tips of Scotland and Ireland, limped home.

One Power Among Many

The defeat of the Armada brought Spain’s unipolar moment to a sharp and dramatic end. In its quixotic search for total domination, it had paradoxically shown its weakness, and in this way, vanquished the aura of invincibility that had been one of its greatest assets. Because of its hubristic approach, it would now have to share prominence on the world stage with the very fast-rising Protestant nations whose rise it had inadvertently financed and had, in a fit of fantasy, later hoped to totally destroy.

While the country would remain an important European player for at least the next half-century, it was soon eclipsed by both France and England in terms of power and importance. But this stark reality was slow to penetrate into the minds of the Spanish leadership class.

And hence they went on pursuing costly wars they were unable to win, wars that were paid for through borrowed money and over-taxation, and whose only palpable achievements were further pauperization of the common people and the creation among them of a deep and largely amoral cynicism regarding the high-sounding moralism and ever-growing authoritarianism of the country’s leadership class.

Maybe it’s just me, but I see an awful lot of food for thought for today’s Americans in the history summarized above.

Do you?

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: Brownstone Institute Read the original article here: https://brownstone.org/