Since its inception, the European project has always aimed to bring about the end of history on the continent, and to finally put the ceaseless cycle of war, extremism and imperialism that had torn Europe apart for a thousand years to rest.

Yet history’s severed heads have a troublesome habit of growing back. The Russian invasion of Ukraine served as a powerful reminder of this reality for the European mainstream, but other unresolved threads of the continent’s brutal and very recent past have also re-emerged in much more subtle ways.

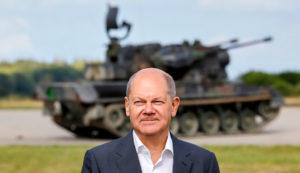

Last week, Poles had hoped that one such long unresolved injustice, the matter of German reparations for the Nazi occupation during the Second World War, would be clarified during German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s visit to reset German-Polish relations under Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s new government. Back in 1953, under the rule of a Soviet-backed puppet government, Poland had formally renounced its claims to much of the reparations it had been promised, leaving the matter unsettled for decades. Yet the issue resurfaced under the previous Law and Justice Party (PiS) government, which, in an effort to appeal to its nationalistic base, argued that the 1953 declaration was inadmissible since it had been made by a government beholden to Russian interests. PiS intensified its efforts in 2022, when it formally requested that Berlin pay Poland over €1.3 trillion in reparations — the total estimated value of Polish wartime damages as determined by Poland’s Jan Karski Institute for War Losses. Although Tusk had previously supported such moves, his government appeared to soften its stance earlier this year, and signalled it was open to receiving other forms of compensation aside from cold hard cash.

Tusk’s new approach and Germany’s newfound willingness to address the reparations issue didn’t emerge from a vacuum — both Poland’s swing from Eurosceptic populist rule to a pro-Brussels centrist government and the recent Rightward shift in the European Parliament have scrambled politics within the bloc. Despite its ultimate loss in this weekend’s elections, the recent success of Marine Le Pen’s National Rally has forced Scholz to prepare for an unruly France in years to come and to look for allies wherever he can find them — opening the door for a rapprochement with a newly sympathetic Poland.

At the joint press conference in Warsaw, though, despite saying all the right things about “a clear view of the past” and the “unmeasurable suffering” of Poles at the hands of Germany, Scholz dashed any hopes that Poland would receive anything close to what it is truly owed. Instead, he spoke of compensation for the few thousand still-living Polish victims of the Third Reich, the opening of a house of memory for such victims in Berlin, and closer defence cooperation with Poland along its eastern border with Russia and Belarus. In response to questions from journalists, he indirectly invoked Germany’s official state position that the 1953 decision had been legally binding, and that Berlin was no longer responsible for fulfilling its reparations obligations to Poland.

The backlash in Poland was immediate, and alongside the predictable criticism from PiS leaders such as President Andrzej Duda, commentators across Polish media denounced Scholz’s comments as “a sign of disregard for the Polish side by our Western ally and partner”. The importance of the matter to everyday Poles was also confirmed shortly after the visit — a new survey released last week found that a majority of Polish citizens supported continuing to demand compensation from Germany for the war.

Getting Germany to pay the full cost of reparations to Poland was always going to be a Herculean task politically, and PiS’s all-or-nothing approach had been bound to fail. But even in trying to make good with a Polish government that had pivoted back to his camp after years of PiS rule, Scholz offered Poland — which proportionally suffered more civilian deaths than any other nation during the war — little more than symbolic gestures and nice words about German guilt, all while leaning on flimsy, decades-old legal arguments. This attitude plays into a long-running and convenient logical fallacy that has allowed modern Germany to divorce itself from its Nazi past: that because it has reformed itself ideologically and spiritually since the Third Reich, it deserves to be tacitly absolved of its sins without having to foot the bill for them in full.

This attitude, which hardly started with Scholz, underscores the enduring lack of understanding among modern German leaders when it comes to contemporary Polish political identity. Although wartime reparations themselves may not be front-of-mind for every Pole, Scholz’s unserious approach to the matter speaks to a much broader concern Poles have about Western Europe’s continued inability to treat their country with dignity in the international arena — especially at a time when Poland has become so crucial for countering the increasing threat to the continent from Russia.

This isn’t to say that Germany has been wholly dismissive of the reparations issue. In 1992, two years after German reunification, Berlin did in fact pay Poland a portion of what it was owed, granting Polish victims of the Nazis around €295 million before disbursing additional funds for Poles who had been forced into slave labour in years afterward. But throughout its relationship with Germany, Poland has repeatedly had to balance its historical grievances with the needs of the present. In 2004, shortly after Poland joined Germany as a member of the EU, the Polish government itself issued a statement confirming that it had lost its right to full reparations in 1953. In the interest of European integration, Poland found it more advantageous to let go of history and satisfy itself with what it had received from Germany, at least for the time being.

Yet on the eve of yet another opportunity to gain the recompense that their country is owed, Polish leaders’ contemporary political interests appear to have trounced earnest desires for full historical justice once again. With his eye on Poland’s most immediate concerns, Tusk declared that he had heard what he needed to hear from Scholz and agreed to effectively put the wrongs of the past aside in exchange for Germany’s help with the pressing security challenges on Poland’s doorstep.

It would, however, be in Tusk’s interest to keep up the pressure on Scholz to satisfy Poland’s demands. Arguments that he has been too conciliatory towards Germany and other European heavyweights have historically been easy fodder for the narratives of PiS and other Right-wing parties, and although Tusk’s party came out on top in Poland’s European elections last month, the far-Right Confederation party’s strong showing should set off alarm bells in his mind about the future of Poland’s electorate. His failure to secure meaningful reparations at such an opportune moment in Poland’s relationship with Germany would haunt his political prospects not only with Poland’s Right, but also with parts of his own base, too. While it may indeed be the case that Poland has no leg to stand on with regard to reparations under international law, as Poland’s Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski said in February of this year, “the issue of moral, financial and material compensation has never been realised”.

This point is particularly salient because the reparations process at the end of the war was indisputably tarnished by politics and corruption. At Potsdam in 1945, the Western Allies gave the USSR the right to dispense reparations from Germany on behalf of Poland, which, after the war, became a Soviet satellite state. Poland received only a portion of the machinery, raw materials and military hardware the Soviets seized from Germany on its behalf after the war, until of course the USSR compelled Poland to make its 1953 declaration in an effort absolve communist East Germany from further obligations. As a result, the country that would have likely benefited the most from its full share of reparations was robbed of them prematurely — a reality that, while unchangeable in the eyes of the law, remains otherwise indefensible to this day.

Germany has been critical for Poland’s post-Cold War development and national security, which has made these historical loose ends difficult to satisfactorily address. But adequately dealing with history and developing a mutually beneficial relationship should not be a binary choice — the latter would only be strengthened through the former. And even if full reparations to the tune of over €1 trillion is out of reach, alternative forms of compensation, like rebuilding historical buildings the Nazis destroyed across Poland, additional funds for economic development, and payments not just to still-living survivors, but also to the countless families across Poland that remain impacted by the war almost 80 years later are all on the table as substitutes.

Satisfying such material demands would be a step towards not only closing the darkest chapter in Polish-German relations and delivering justice for its victims, but also affirming that Poland is indeed an equal partner to Germany in a rapidly changing EU. While Europe’s West may be content to live out its post-historic fantasy, in Poland and other eastern members of the bloc, the past haunts our lives at every turn. As it becomes clearer that the EU’s destiny will be defined by its eastern half, acknowledging this and addressing it seriously is no longer a luxury for the European mainstream — rather, it has now become central to its very future.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/