Everyone wants to be a free thinker, or at least to be seen by others as thinking freely. Sometimes we imagine even our most embarrassing acts of conformism as daring ventures of freedom.

The terms we use to express this delusion vary depending on political persuasion. In the United States, progressives can see themselves as dissenting members of a “resistance” to Trump, while centrists oppose both the President and woke shibboleths by holding “heterodox” views. Rightward, those in Trumpworld denounce opponents as automata. Witness tech billionaire Sam Altman bending the knee to Trump on X, where he apologised for his earlier opposition to the President: “i wish i had done more of my own thinking and definitely fell in the npc trap.”

Thinking for oneself is perhaps most difficult among communities — Left, Right, and centre — that celebrate ostensible dissent. Defining independent thinking in terms of outspoken opposition to dominant views, would-be dissenters often end up falling into either mere contrarianism or uncritical adherence to views popular in their own circles.

Few American thinkers have confronted this problem as unsparingly as the 20th-century cultural critic Harold Rosenberg (1906-1978). The central concerns of his wide-ranging life in letters were paradoxes of non-conformity in a society at once founded on individual freedom and dominated by clichés. He rose to prominence in a postwar United States where unprecedented national wealth and power combined with a growing unease among intellectuals about the stultifying effects of mass media and the incapacity of citizens to exercise independent judgment. Our collective repetition of clichés and inauthentic opinions, regardless of the subject matter, degrades the freedom of thought on which politics — and indeed ethics — depend.

Best known today for his advocacy of Abstract Expressionist painting, Rosenberg’s collections of essays — all of them now out of print — trace his struggles against what he saw as deceptive forms of pseudo-freedom in everything from the visual arts to politics. For decades, his career was marginal and precarious. He subsisted on a combination of freelance essay-writing and consulting work for the Advertising Council of America — a job that contradicted his public condemnations of American capitalism. After the publication of his first book, The Tradition of the New (1959), however, Rosenberg was not only famous, but a bona fide member of the establishment he had once criticised. He took a professorship at the University of Chicago and became an art critic for The New Yorker, where he often lamented whatever seemed to be fashionable in contemporary painting (he especially loathed Andy Warhol, whom he saw as a boring fraud). He became one of the country’s most influential critics from the Sixties until his death in 1978.

But it was at the magazines aimed at fellow intellectuals where Rosenberg emerged as an insightful and divisive, if relatively obscure, critic. He was long associated with the Partisan Review, one of the leading “little magazines” of the American mid-century. Its editors and writers prided themselves on their independence from both American popular culture and dogmatic Leftism. Throughout the late Thirties and Forties, their line had shifted from an anti-Soviet Marxism towards the political centre, while retaining a small but influential readership and intellectual cachet. Although politically in favour of democracy, the Partisan Review was culturally elitist. It put into circulation early critiques of mass culture, and presented the intellectual in a capitalist democracy as obligated to reinforce his sense of superiority over the swine feeding at the trough of popular culture.

By 1948, Rosenberg’s relationships with many members of the circle around the magazine were increasingly fraught. He hoped to attain a position at the magazine’s helm but personal qualities such as belligerent self-assurance and a habit of sleeping with other men’s wives handicapped him. Among the rivalries he nurtured during this period, his reciprocal hatred of fellow Partisan Review writer Clement Greenberg was particularly important. While both men were, along with the art collector Peggy Guggenheim, the earliest and most intelligent champions of Abstract Expressionism, they disagreed about why the movement mattered.

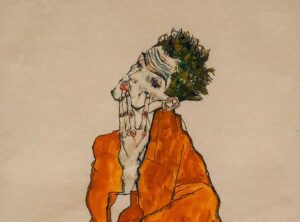

For Greenberg the work of Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and others was the latest development in a centuries-long process of Western art moving away from literal-minded depictions of reality and towards the free play of form and colour. Rosenberg, in contrast, saw what he preferred to call “Action Painting” as a decisive break with the past. He regarded these paintings as expressions on canvas of the postwar existential crisis articulated by Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus: a response to what he took to be the collapse of traditional systems of meaning and the threat of nuclear annihilation. According to Rosenberg, a “good” work of art was an authentic one, by which the artist was able to register his own free, creative, personal grappling with the situations that imperil us all.

As he developed his interpretation of abstract painting as the visual equivalent of existentialism, Rosenberg became increasingly sceptical of the intellectuals closest to him. His sharpest essay in this vein, “The Herd of Independent Minds”, appeared in the Jewish magazine Commentary in 1948. As his biographer Debra Bricker Balken observes, he had intended to publish it in the Partisan Review, possibly hoping to offend his former friends at the magazine.

Thinkers associated with that era’s little magazines — the distant ancestors of n+1 on the Left and The Point or Liberties in the centre today — wrote as if they were separate from American mass culture. But they were, he warned, only members of a subcultural bubble with its own clichés and jargon (these days, every little magazine seems to have its own merchandise as well), part of a “mass culture of small groups”.

This is bad enough, although perhaps smug, self-satisfied in-group cosiness is the inevitable consequence of belonging to any set (and must be preferable to the alternative of having no interlocutors). As Joseph Keegin has pointed out, for example, Right-wing populists tend to repeat comforting political slogans identical in form (if opposite in content) to the much-mocked “In This House We Believe” signs of their progressive opponents. It could be added that even small groups outside the bustle of mass politics still depend on some measure of sloganeering and dogmatising, however much smaller in scale.

We’re always bound to impose some allegiance to common beliefs in order to have a community at all, even a community of intellectuals. But there are some delusions, Rosenberg hoped, that we can avoid. He particularly admonished his Left-liberal free-thinking friends for imagining themselves to be educating the public by speaking, in authoritative tones, about the supposed features and needs of “our” moment or generation. This was, he hoped, a curable vice — although it remains a common one today. Commentators, as a glance at Substack will show you, still love to yap about the “vibes” in which we are all supposedly participating, delineating the purported qualities of ever shorter micro-periods of contemporary history.

Invariably such pundits, Rosenberg noted, write as if they were somehow not themselves caught up in the trends of the day. While acting as an anthropologist of the shifting folk beliefs of the masses — or of rival sets of intellectuals — one fails to notice how one’s own thought is shaped by peers, clichés, and the pressure to conform.

He called on intellectuals to follow the paths of the best artists, those who confront the confusing, disjointed, overwhelming aspects of their individual experience, which somehow “never belongs to the right time and place”. Instead of taking a bad faith stance by which you imagine that other people are caught up in vibes which you, as a free thinker, can analyse, Rosenberg suggests you start by tracking how your own experience comes into friction with the received ideas of your tribe and the limits of your self-categorisations. Only then can you hope to interact with others authentically, rather than giving just another twist to clichés currently in favour.

Rosenberg, however, often despaired that neither in punditry nor painting was such authenticity possible (a fear he shared with Arendt). After all, as he was writing in 1948, existentialism had already become a fad, and abstract painting was about to become a top-selling commodity on the global art market. The arc of his own career may seem discouraging, taking him from independent little magazines to The New Yorker, perhaps the most condescendingly smug of America’s middle-brow publications. A typical New Yorker essay (such as this recent piece by historian Daniel Immerwahr), whether in the age of Arendt and Rosenberg or in the present, appeals to a supposed consensus view among urban, educated upper-middle-class liberals, while offering what the writer presents as a surprising twist on that common sense. Such writing confirms the reader in their sense of having the capacity to allow their opinions to be gently challenged by well-edited experts. It perpetuates a delusion of free thought.

Yet perhaps there is room for hope even here. If neither small readerships nor noisy pride in thinking for oneself makes for genuine intellectual freedom, neither perhaps does the opposite mean conformism. Arendt, after all, wrote her indictment of the trial of Adolf Eichmann, in which she made her most perceptive — and controversial — judgements on the power of cliché, in the pages of The New Yorker. Then again, amid the rancorous debates surrounding her reportage, few readers at the time were able to make sense of her now-famous arguments about the “banality of evil”. We cannot assure ourselves that we are thinking freely because we have unpopular opinions, or because our ideas seem to be misunderstood. We must conversely at least hope that sometimes genuinely novel, authentically held, and, more importantly, true ideas can be expressed even through the channels of mass media.

In accordance with his own emphasis on the difficulty of cultivating freedom of thought, Rosenberg had no direct intellectual heirs. His closest student and literary executor, Michael Denneny, abandoned a nearly completed PhD thesis on the history of aesthetic theory (under the direction of Arendt) to become a publisher of a gay men’s magazine that imitated the form and tone of The New Yorker. It was as if he were out to prove that a glossy commercial publication could both rally a community (or consumer demographic) and remain true to Rosenberg’s legacy. More recently, in a similar spirit, the art critic Travis Jeppesen, newly named senior editor of Artforum, has called for a revival of Rosenberg’s highly personal and engaged style of writing about art, by which works and artists were judged by the power (or failure) to incite spectators to think anew.

Artforum, rocked by debates about the war in Gaza, and operating amid a global arts market devoted equally to pseudo-political posturing and pseudo-intellectual sales pitches for expensive commodities of dubious aesthetic value, is surely an imperfect venue for independent thought. But the lesson of Rosenberg’s critique in “Herd of Independent Minds” is that there is, in fact, no publication, network, style, or attitude in which we can take permanent refuge from the danger of cliché, or the still more insidious danger of believing ourselves — and people like us — to have secured both intellectual independence and membership in a group.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/