The war on free speech is hardly a novel phenomenon, instead mutating over the centuries. What is new, however, is its global aspirations: today, the conflict takes the form of a world war.

You can see its shadow in every Western country, from the US and Canada to Ireland and Australia, as well as in every multinational organisation, from the EU to the UN. Rising levels of hate speech and misinformation, we are told, make it more urgent than ever for governments, corporations and multilateral organisations to adopt stronger measures to protect vulnerable populations online.

It is for this reason that Biden’s Department of Homeland Security recently created a “Disinformation Governance Board”, the European Commission crafted a new Digital Services Act and Code of Practice on Disinformation, and the UN is proposing a “Code of Conduct for Information Integrity on Digital Platforms”. All of these initiatives are allegedly the product of good intentions; all of them, however, are rooted in the same fallacy: there is little evidence to suggest that hate speech and misinformation are on the rise. On the contrary, Western countries are more tolerant of racial, religious and sexual minorities than ever before. To take one example, the percentage of Americans who approve of marriages between white and black Americans has risen from 4% in 1958 to 87% in 2013 to 94% in 2021.

There are, of course, plenty of examples of misinformation and hatred online, and Twitter and Facebook are right to reduce their spread — but often the threat is exaggerated. The Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD), for instance, recently published a study that concluded that antisemitism was increasing on Twitter. But there is no definitive evidence of rising hate online. The ISD study counted tweets criticising George Soros which didn’t mention his Judaism as antisemitic. Elsewhere, “hate speech” includes the reluctance of some people online to use female pronouns when referring to transwomen — even though one might oppose using female pronouns for natal males and harbour no animus toward transwomen.

Here we can see that what people label as “hatred” and “misinformation” is often merely an opinion they don’t like or which they fear will encourage bad behaviour. In both the UK and the US, this led to government officials demanding that social media platforms censor “often-true” content, including about Covid vaccine side effects, out of fear that such stories would result in vaccine hesitancy.

What’s more, Facebook and Twitter have also started deleting a significant amount of true content. Between 2020 to 2021, for example, Facebook censored claims that the coronavirus came from a Chinese lab, even though that was always as likely, if not more so, than the natural-origin hypothesis. Twitter also censored an accurate New York Post story about Hunter Biden’s laptop while allowing supporters of his father, Joe Biden, to falsely claim it was a result of “Russian disinformation”.

The global campaign to censor disfavoured views on Twitter and Facebook is therefore rather curious. If there is no evidence that hatred and misinformation are increasing, and ample evidence of inappropriate censorship of true and accurate information, why are politicians across the West calling for greater power to censor?

Some of the demand certainly appears to be grassroots. Since 2016, an increasing number of psychologists have started to document the rise of “concept creep”, the dramatic expansion of what people in Western societies consider to be “harmful”. It used to be that one would have to show physical or financial harm from speech for it to be restricted: often, one would have to commit fraud, incite violence or ruin a person’s career. Today, by contrast, a growing number of people consider petty offences, such as calling a transwoman “he” or denouncing Soros as a “globalist,” to be the cause of “real-world harm”.

Yet this support cannot be taken in isolation; more often than not, it is the result of funding from governments. It was, after all, Renee DiResta, a former CIA Fellow at Stanford University, who proposed that DHS create a “Disinformation Governance Board”; in Brazil, meanwhile, a Supreme Court judge is leading calls for greater censorship; in Canada, it is Justin Trudeau who has sought a crackdown on wrongspeech; and in the UK, the Institute for Strategic Dialogue is funded by the UK government and the US Department of Defense.

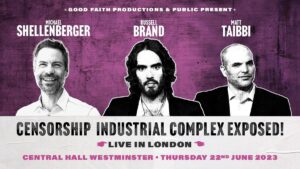

Perhaps it is unsurprising, then, that these efforts all share an elitist, anti-populist strain. Many of the government agencies, contractors and NGOs that are advocating for greater censorship have ties to the military, intelligence and security organisations, spawning what I term the “Censorship Industrial Complex”. How this is manifested is relatively straightforward: fearing that a wave of populist political victories would undermine Nato, the EU and the Western Alliance, government intelligence, military and security officials engaged in disinformation campaigns, such as the one claiming Trump was a Russian asset and that the Hunter Biden laptop was Russian disinformation, while demanding censorship of populist and anti-war voices.

Together, these measures constitute nothing short of a world war on free speech. After all, the intention of the UN and the EU is to censor disfavoured speech at a global level, specifically by insisting that Twitter and Facebook obey their dictates or face massive fines and nationwide restrictions.

So far, one of the greatest obstacles to these censorious ambitions is Elon Musk, the owner of Twitter, who has publicly stated that he refuses to comply with EU rules. But Musk is also under enormous pressure from advertisers, many of whom stand with the censorship advocates and heads of state. Under pressure from the Turkish government, for instance, Musk was forced to censor disfavoured Turkish journalists or face Twitter being cut off in the country entirely.

Even if this were not the case, free speech has never been a gift that can be secured by one person. Rather, for it to survive, it is up to the citizens of the world to insist that governments stop demanding, directly or indirectly through the NGOs they fund, that social media platforms censor disfavoured views. And to the extent that content moderation by social media companies is inevitable, they must be transparent about what content they are restricting, how they are restricting it, and why.

Nor is any of this outside the realms of possibility. It was encouraging, for instance, to see the Department of Homeland Security shut down its “Disinformation Governance Board” three weeks after introducing it, following an online backlash. In Europe, too, resistance is growing to the Digital Services Act. And, on Twitter, we have seen rowdy and rousing opposition to the UN’s proposed “Code of Conduct for Information Integrity on Digital Platforms”, as well as new censorship proposals in Ireland, Brazil, Canada, the US, Australia and New Zealand.

Most of all, we need to change how we perceive ostensibly earnest calls for reducing “hate speech” and “misinformation”. We need to train our ears to hear such language as pretexts for government censorship. We need to remind our fellow citizens of the enormous progress we have made against hatred and discrimination over the decades and centuries. And, perhaps most of all, we should feel insulted, patronised and threatened by those elites who are trying to undermine that precious thing we have been fighting for since society was born: our right to express ourselves, however much it might offend them.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/