What is the formative connection between the private self and other people? Or, as the architect of libertarianism Ayn Rand once put it, how should we order “the two principles fighting within human consciousness — the individual and the collective, the one and the many, the ‘I’ and the ‘They’”? Today, the question looms large because of the “social” part of social media, though we’re probably all too distracted checking our mentions to notice. In wartime Europe, the issue was more obviously pressing — for other people tended to breathe down your neck in ways you couldn’t ignore. They hunted in packs, attacked in mobs, wandered about desperately in droves, and capitulated in herds.

During the Thirties and Forties, four brilliant but unknown young thinkers — Simone Weil, Simone de Beauvoir, Hannah Arendt and Ayn Rand herself — were obsessed with questions about the individual versus the social world. Unfamiliar to each other, they wondered how best, in Beauvoir’s words, “to make oneself an ant among ants, or a free consciousness facing other consciousnesses”. Their respective philosophical conclusions and the surrounding life events that helped give rise to them are the subject of a wonderful book, The Visionaries by the German author Wolfram Eilenberger.

No member of this quartet was a natural team-player; all were fiercely non-conformist in their own ways. The book depicts them living through a tumultuous decade (1933-43) that included Stalin’s Holodomor, the Spanish Civil War and the rise of Hitler. To Arendt, history resembled not so much an arc bending towards justice as something more like the vision of her suicidal friend Walter Benjamin: “one single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage”. Weil accused the “whole of the 19th century” of believing, wrongly, “that by walking straight in front of one, one necessarily rises up into the air.”

Metaphysical questions assumed to be long settled took on new political urgency as legal rights were repealed, hostilities stoked and the death camps built. The challenge, as far as Arendt was concerned, was for Jews like her to “fight like madmen for private existences with individual destinies” against the forces that would dehumanise them. From 1933 on, she wandered rootless and alienated across Europe, settling uneasily for a while in Paris before being forced to move on again.

Like Arendt, Rand and Weil were also Jewish, relegating them to the status of metaphysical Otherhood in the eyes of many. Rand’s prosperous Russian family had lost nearly everything during the revolution. Weil, assimilated (at least superficially) in a bourgeois French family, suffered less from antisemitism than the others, but still was forced to leave for England in 1942. As a non-Jew, Beauvoir underwent the least personal upheaval, but even she had a breakdown during a flight from the Germans in 1940.

Between them, these thinkers produced a fascinating spectrum of philosophical positions, each inflected by thoughts and feelings about the chaos around them. At one pole was the atheist Rand, arriving in the States aged 21 with a visceral hatred of totalitarianism, and with a self-willed, asocial, rational egoist in mind as a moral hero — someone a bit like her, it seems. Autonomy was everything, suffering was pointless, and the self was most free when alone.

Rand rejected any Christian or socialist calls to altruism or “equality” as vehemently as she rejected tyranny from the Russian state. Equality meant only interchangeability, which meant a descent into mediocrity and nothingness. Refusing modesty as a refuge of the feeble-minded, she would declare in her diary that “Nietzsche and I think…”. She dreamed of becoming completely impervious to other people’s opinions — to “refuse, completely and uncompromisingly, any surrender to the thoughts and desires of others”, as she put it for one of her fictional protagonists — and very nearly managed. In 1943, as her family still starved back in Leningrad, her novel The Fountainhead finally took off. She negotiated an unheard-of sum of $50,000 for the Hollywood film rights and bought herself a mink coat.

At the other end of the spectrum was the admirable Weil, equally eccentric and passionate in her attempts to make a moral art out of living, and the real star of the book. During a short and intensely lived life she moved from Marxist-inspired socialism to ascetic Christian mysticism, but was always drawn to self-sacrifice and suffering as a means of understanding others. She sent all her spare money to the poor; wouldn’t eat at her parents’ house unless she could leave the cost of a restaurant meal on the table afterwards; and worsened her already fragile health by getting a job in a factory, in order to better understand the experience of workers. During the Spanish Civil War, she became the International Brigade’s least useful volunteer, determined to carry out secret missions for the Republic but short-sighted to the point of near-blindness and unable to shoot a rifle.

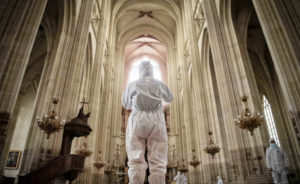

Physically emaciated and tortured by terrible headaches, she deliberately sought out sacred music in churches to transform her physical suffering into meaning. By the end of her life, Weil was advocating total selflessness and renunciation of will, and framing the act of suffering as a direct route to communion with God. But even as she lay dying in a Kent hospital in 1943 — muttering verses, refusing food to the frustration of her doctors, and telling nurses to send her allocated milk to the starving — she still found the energy to write to the leaders of the Free France movement, remonstrating about their failure to send her behind enemy lines on a solo mission.

In between these two characters and outlooks are placed the more moderate Beauvoir and Arendt. Partly because of the persecution she suffered, Arendt appears the more sympathetic one here, and the more politically serious. While being chased across Europe, she agonises about Jewish identity and the self-destructive futility of trying to “assimilate”, feeling lonely and unwelcomed wherever she fetches up.

Living precariously as a refugee after escaping from a French internment camp, she starts to articulate the ideas that would later inform her famous analysis of totalitarianism as an émigré to the United States. Internees in camps were not being arrested for anything they had personally done, she noticed, and no difference was made between the innocent and the guilty. The individuality and inner life of a person was irrelevant — was treated as non-existent, even. The Nazi plan, embraced by collaborating French too, was to turn “every individual human being into a thing that would always behave the same way under identical conditions”.

In comparison to the travails of Arendt, the life of the young Beauvoir can’t help seeming slightly decadent. Granted, she waxes enthusiastically about the importance of “metaphysical solidarity” with others as a precondition of personal freedom, but makes it sound all rather grubbily transactional — I’ll grant you recognition, if you grant me some. While, by force of circumstance in the Paris of 1936, Arendt and her fellow refugee lover are living hand-to-mouth in sparsely furnished hotels and wandering aimlessly between cafes during the day, Sartre and Beauvoir are doing the very same thing — by choice, for kicks.

The immediate focus of both Sartre and Beauvoir is not the suffering millions, but their shared “family”, composed of young lovers and acolytes. When not reading or writing, Beauvoir conducts a complicated romantic schedule that would make the average polycule these days feel inadequate. Resembling Rand in her rather sociopathic detachment from other people’s feelings, she treats this quasi-incestuous group as a psychological testing chamber through which she can analyse various permutations of what the existentialists called “Being-for-others” — and then set them within her novels.

One of Eilenberger’s strokes of genius is to reflect the book’s content in its form. Just as hidden aspects of the self are revealed only in a process of comparison with others, so too do elements of each woman’s life and outlook emerge in fascinating relief by juxtaposition with the other three. As the episodic narrative unfurls, strange harmonies and discords between the thinkers appear as if in musical counterpoint.

Poles apart, Rand and Weil both end up thinking of social life as a source of evil, though for different reasons. For Weil, Plato’s “Great Beast” — public opinion — can only lead us away from God. For Rand, it can only lead us away from the god-like self. Arendt embraces love between two people as the antithesis of totalitarian impersonality, while Weil treats romantic love as “manifestly unjust and morally random”. Just as Arendt argues that Jewish assimilation into society requires a destructive embracing of antisemitism within the self, so too will Beauvoir eventually go on to argue in The Second Sex that the assimilation of women into a universal “humanity” requires something similar — but with misogyny taking the place of antisemitism. Meanwhile Rand, Weil, and Beauvoir all think of themselves as adopting masculine roles.

The basic philosophical questions addressed so ardently by these iconoclasts have not gone away. Invasion and war are back on the continent, along with dehumanising war crimes and the strategic othering of ethnic and national populations — all encouraged by leaders who sneer at democracy. But even without all that, there are quieter and more everyday invasions: of your mind, for instance, filled up by other people’s thoughts and feelings every time you look at a screen.

The boundary of the self in relation to others has never been more porous. Resistance to the “Great Beast” is increasingly difficult, even if we now answer to bureaucrats in HR departments and not to party apparatchiks. In an age of virtual and machine-mediated relationships, we invent new selves online for the benefits of imaginary beings but take every opportunity to avoid other people in the flesh. In doing so, we avoid ourselves. Indeed, for some of us, lost in online worlds, Being-for-others in Beauvoir’s sense barely gets going. And destructive ideology can easily seep into the gaps where human contact used to be.

Equally, the public square has also got a lot noisier since 1943, and it’s even harder to tell who the bad guys are. Widespread cultural familiarity means that, perversely, the narrative of a minority being cruelly dehumanised can be cynically recycled by pretty much any group seeking power or attention, no matter how ludicrous the claim at face value. (“Acephobia”, otherwise known as discrimination against asexual people comes to mind — indeed, surely it’s only a matter of time before some bright spark reclaims Simone Weil as an early fighter for asexual rights). Tap into the right tropes and it’s a work of minutes to persuade the guilt-ridden and the gullible that a new identity group is being persecuted horribly, simply because rampant political ambitions are being criticised. The book-burners and censors these days do it in the memory of past victims of totalitarianism, and many onlookers don’t know which side to take. Even worse, the phenomenon of confected-grievance-as-power-grab allows many to dismiss genuine social ills in the same light.

Still, despite the epistemic confusion, we have to keep on trying. As Arendt wrote presciently in 1951: “The self-compulsion of ideological thinking ruins all relationships with reality… The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (the standards of thought) no longer exist.” In other words: technologies may come and go, but the challenge of staying an individual in the face of the mob is always with us.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/