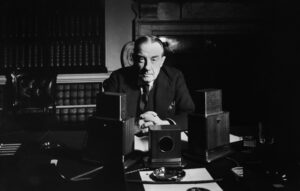

To his army of ardent followers, Tom Holland has a unique ability to bring antiquity alive. An award-winning British historian, biographer and broadcaster, his thrilling accounts offer more than a mere snapshot of life in Ancient Greece and Rome. In Pax — the third in his encyclopaedic trilogy of best-sellers narrating the rise of the Roman Empire — Holland establishes how peace was finally achieved during the Golden Age, with a forensic recreation of key lives within the civilisation, from emperors to slaves.

This week, Holland came to the UnHerd club to talk about Roman sex lives, Christian morality, and the rise and fall of empires. Below is an edited transcript of the conversation.

Freddie Sayers: Let’s kick off with the very first year in your book.

Tom Holland: It opens in AD 68, which is the year that Nero committed suicide: a key moment in Roman history, and a very, very obvious crisis point. Nero is the last living descendant of Augustus, and Augustus is a god. To be descended from Augustus is to have his divine blood in your veins. And there is a feeling among the Roman people that this is what qualifies you to rule as a Caesar, to rule as an emperor. And so the question that then hangs over Rome in the wake of Nero’s death is: what do we do now? We no longer have a descendant of the divine Augustus treading this mortal earth of ours. How is Rome, how is its empire, going to cohere?

FS: It seemed to me, when I was reading Pax, that there was a recurring theme: a movement between what’s considered decadence, and then a reassertion of either a more manly, martial atmosphere, or a return to how things used to be — to the good old days. With each new emperor in this amazing narrative, it often feels like there’s that same kind of mood, which is: things have gotten a bit soft. We’re going to return to proper Rome.

TH: It’s absolutely a dynamic that runs throughout this period. And it reflects a moral anxiety on the part of the Romans that has been characteristic of them, really, from the time that they start conquering massively wealthy cities in the East — the cities in Asia Minor or Syria or, most of all, Egypt. There’s this anxiety that this wealth is feminising them, that it’s making them weak, it’s making them soft — even as it is felt that the spectacular array of seafood, the gold, the splendid marble with which Rome can be beautified, is what Romans should have, because they are the rulers of the world.

That incredible tension is heightened by class anxieties. There’s no snob like a senatorial snob. They want to distinguish themselves from the masses. But at the same time, there’s the anxiety that if they do this in too Greek a way, in too effeminate a way, then are they really Romans? And so the whole way through this period, the issue of how you can enjoy your wealth, if you are a wealthy Roman, without seeming ‘unRoman’, is an endearing tension. And of course, there is no figure in the empire who has to wrestle with that tension more significantly than Caesar himself.

FS: The 100-odd years that you’re covering in this volume is a period of great peace and prosperity and power, and yet at each juncture, it feels like there’s this anxiety. That’s what surprised me as a reader. There’s this sense of the precariousness of the empire — maybe it’s become softer, maybe it’s decadent, or maybe it needs to rediscover how it used to be.

TH: And, you see, this is the significance of AD 69, “the Year of the Four Emperors”, because the question is, are the cycles of civil war expressive of faults? Of a kind of dry rot in the fabric of the Empire that is terminal? Of the anger of the gods? And whether, therefore, the Romans need to find a way to appease the gods so that the whole Empire doesn’t collapse. This is an anxiety that lingers for several decades. It looks to us like this is the heyday of the Empire. They’re building the Colosseum, they’re building great temples everywhere. But they’re worrying: “Have the gods turned against us?”

And of course, there is a very famous incident, 10 years after the Year of the Four Emperors, which is the explosion of Vesuvius. And this is definitely seen as another warning from the gods, because it coincides with a terrible plague in Rome, and it coincides with the incineration (for the second time in a decade) of the most significant temple in Rome — the great temple to Jupiter on the Capitol, the most sacred of the seven hills of Rome.

Romans offer sacrifice to the gods or you pay dues to the gods rather in the way that we take out an insurance policy. And if the gods are busy burying famous towns on the Bay of Naples beneath pyroclastic flows, or sending plagues, or burning down temples, then this, to most, is evidence that the Roman people have not been paying their dues. So a lot of what is going on — certainly in the imperial centre — in this period, is an attempt to try and get the Roman Empire back on a stable moral footing.

FS: The question of gender and sex crops up a lot in your book. It did strike me that pretty much all of the extremely masculine generals in your book — many of whom go on to become emperors — are having sex with young men.

TH: Well, it wasn’t just young men, but we’ll come to that. There is always a temptation to emphasise the way in which the Romans are like us, a mirror held up to our own civilisation. But what is far more interesting is the way in which they are nothing like us, because it gives you a sense of how various human cultures can be. You assume that ideas of sex and gender are pretty stable, and yet the Roman understanding of these concepts was very, very different to ours. For us, I think, it does revolve around gender — the idea that there are men and there are women — and, obviously, that can be contested, as is happening at the moment. But the fundamental idea is that you are defined by your gender. Are you heterosexual or homosexual? That’s probably the great binary today.

For the Romans, this is not a binary. There’s a description in Suetonius’s imperial biography of Claudius: “He only ever slept with women.” And this is seen as an interesting foible in the way that you might say of someone, he only ever slept with blondes. I mean, it’s kind of interesting, but it doesn’t define him sexually. Similarly, he says of Galba, an upright embodiment of ancient republican values: “He only ever slept with males.” And again, this is seen as an eccentricity, but it doesn’t absolutely define him. What does define a Roman in the opinion of Roman moralists is basically whether you are — and I apologise for the language I’m now going to use — using your penis as a kind of sword, to dominate, penetrate and subdue. And the people who were there to receive your terrifying, thrusting, Roman penis were, of course, women and slaves: anyone who is not a citizen, essentially. So the binary is between Roman citizens, who are all by definition men, and everybody else.

A Roman woman, if she’s of citizen status, can’t be used willy-nilly — but pretty much anyone else can. That means that if you’re a Roman householder, your family is not just your blood relatives: it’s everybody in your household. It’s your dependents; your slaves. You can use your slaves any way you want. And if you’re not doing it, then there’s something wrong with you. The Romans had the same word for “urinate” and “ejaculate”, so the orifices of slaves — and they could be men, women, boys or girls — were seen as the equivalent of urinals for Roman men. Of course, this is very hard for us to get our heads around today.

The most humiliating thing that could happen to a Roman male citizen was to be treated like a woman — even if it was involuntary. For them, the idea that being trans is something to be celebrated would seem the most depraved, lunatic thing that you could possibly argue. Vitellius, who ended up an emperor, was known his whole life as “sphincter”, because it was said that as a young man he had been used like a girl by Tiberius on Capri. It was a mark of shame that he could never get rid of. There was an assumption that the mere rumour of being treated in this way would stain you for life; and if you enjoy it, then you are absolutely the lowest of the low.

FS: And yet, there are love stories in this period. In your book, you describe Trajan as having “such a passion for boys that an Assyrian king looking to win the emperor’s favour had secured it by getting his son to perform some barbaric dance”. So that’s the kind of decadent type that you’ve been talking about. But then the book ends with the love affair between the Emperor Hadrian and Antinous, which feels very emotional and very different.

TH: Of course, sexual moral standards impose enormous strains on people. Not everyone’s sexuality is suited to cohering to a governing moral code. And for people who enjoyed being a passive partner, who gained emotional sustenance from it, it must have been excruciating.

The great erotic ideal for Roman men in this period is less girls than boys who look like girls. It’s all very Blur: “Boys who like girls, who like…” These boys, known as delicati, would wear make-up, have their hair done in feminine styles and dress as girls. The more feminine they looked, the more of a status symbol they were, and so senators were willing to lavish fortunes on them. As always, it was Nero who took it the furthest. It was said that he kicked his beloved wife, Poppaea Sabina, to death because she’d nagged him for being out late at the chariots. It’s probably not true because he adored her. But after her death, he went looking for someone who resembled her. He found a boy, castrated him and, from that point onwards, this poor boy, Sporus, had to live as Poppaea Sabina.

FS: You say in your book that “an immense reward was offered to anyone capable of implanting a uterus into the eunuch”. He’s literally trying to turn Sporus into a woman.

TH: Of course, he can’t do that. But when Nero dies, this poor boy becomes a trophy of war. First, Otho takes him, and then Vitellius has an idea that he thinks will make him popular with the Roman people: he will order Sporus to dress up as Persephone, and then have him gang-raped to death by gladiators dressed as Hades in the arena. He thinks this is tremendous entertainment — kind of like the World Cup — and that everyone will love it. Of course, Sporus kills himself. I mean, as you would, faced with that. It’s horrible, horrible stuff. But while this scale of exploitation is to our way of thinking unspeakable, it was morally justified to the Romans.

FS: What about the story of Hadrian and Antinous?

TH: Antinous is a stunningly handsome boy who Hadrian seems to have met on his great journey around the Empire. At this time, between Nero’s reign and Hadrian’s, the making of eunuchs had been made illegal. So I think there was a sense that Antinous has the beauty of a eunuch, which makes him incredibly precious. Hadrian sends him back to Rome to be given the cultural upbringing that a partner of Caesar should have. And then, I guess when he’s aged around 15, he comes under Hadrian’s wing.

Now, to our way of thinking, that would be grooming, pure and simple. But that’s not how the Romans saw it. It’s not how the Greeks saw it, either, because they recognised that Hadrian was behaving like a Greek. He wears a beard, like a Greek philosopher. He was known as a young man as Graeculus, the little Greek. There’s a sense in which Hadrian’s adoption of a beautiful Greek boy is like Zeus sweeping up Ganymede to be his cup bearer — or like Hercules and Hylas.

FS: Would you say he had a special licence?

TH: Yes, as the Greeks felt it was flattering to them. But the question that is unknowable is how Antinous felt about it. I personally cannot imagine he would have been anything other than, on one level, very grateful to have been raised up from a provincial backwater. However, it’s also possible that it inflicts untold psychic damage on him, because Antinous ends up dead under very mysterious circumstances in Egypt, at exactly the time when he is starting to sprout a beard and to bulk up. There were many different theories circling around: did he kill himself? Was he murdered? Was he offered up in sacrifice to the gods? Another theory, which I have some sympathy with, is the idea that he faked his own death and ran away. But we just don’t know.

FS: What’s going on in your head when you are researching these characters? Does it make you think differently about our own morality today?

TH: The Roman historian Livy says of his people: “We are known across the world as having the justest punishments.” This is a society that flings people to the lions, sponsors gladiatorial combat and stages crucifixions. But the Romans don’t think what they’re doing is in any way morally depraved; they think it’s absolutely justified.

This is what inspired me to write my previous book, Dominion, which argues that our moral standards, our ways of seeing the world, are rooted in the great Christian revolution. The reason it is so difficult for us to see the world through the eyes of Romans is because our gaze is smeared over with Christian assumptions. My ambition in this new book is to write a kind of anti-Dominion, which looks at the world entirely through Roman eyes. The Christians in this narrative, who feature in a couple of paragraphs, are like Mesozoic shrews in an ecosystem dominated by dinosaurs. The dinosaurs are crashing around, bellowing and generally being Roman, while the Christians are so tiny you barely see them. But of course, as with the mammals, it’s the Christians who in the long run will inherit the world.

FS: Is there anything you think the Romans were right about that we’ve lost in the Christian era?

TH: The question that haunts me, whenever I write about the Romans, is why am I so fascinated by them? When I went to Sunday school, and saw pictures of Jesus in front of Pontius Pilate, I was always on the side of Pontius Pilate. He was kind of glamorous: he had eagles, he had purple robes. By contrast, Jesus was a massive scruff. I much preferred the Romans, and I think that this speaks to something that is kind of inherent. There is a certain admiration, and a dread, and an appeal in power.

It’s hard for us to acknowledge this, partly because we are so influenced by the weathering effect of centuries and millennia of Jewish and Christian thinking. It’s also because we exist in the shadow of the Fascists. And the Fascists were the first group of people in the history of Christian Europe who consciously repudiated not so much the institutions of Christianity — as the French or the Russian revolutionaries did — but the core morality of Christianity. They absolutely rejected the idea that the last should be first, that the strong and the rich have a duty of care to the weak and the poor. And that’s why I think we see the Nazis as the embodiment of evil. I think we’ve internalised the fear that identifying with the Romans is to risk becoming Fascists.

FS: Do you think that the incredible success of the Roman Empire was due to the fact that so much power was concentrated in one person?

TH: [Edward] Gibbon famously said that mankind was at its “most happy and prosperous” in the period following the rule of Vespasian and his two sons. Listening to me talk about this period, you might think, “well, that’s insane, it sounds horrible”. And of course, for lots of people, it was horrible. Yet, by and large — with the exception of the Year of the Four Emperors and the occasional revolt — vast stretches of the world that had previously been convulsed by conflict were stable. The whole of the Mediterranean was bound together under a unitary power; the Romans call it mare nostra, “our sea”. And that’s the only time this has ever happened in recorded history. The result was an equivalent of globalised trade; different areas of the Empire start specialising in aspects of economic activity that they’re particularly suited to, confident that there is a single framework of law, that there are shipping lanes that will be patrolled, that they won’t be attacked by pirates. This is, by relative standards, a golden economic period.

FS: In your book, you quote Pliny saying: “Who would deny, now that the greatness of Rome’s Empire enables opposite ends of the globe to communicate with one another, that life is improved by the interchange of commodities, by a partnership in the blessings of peace and by the general availability of things.” This does sound a bit like today’s semi-globalised free market.

TH: In the introduction, I quote a Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who argues that the Roman Empire in the second century, under Trajan and Hadrian, had the wealthiest economy prior to the emergence of modern capitalism in the Netherlands and England in the 17th century. I’m not remotely qualified to say whether or not this is true, but it is clearly the case that this is a spectacularly wealthy period. And people like Pliny absolutely do celebrate it.

There are, however, people who see this wealth as evidence of Rome’s monstrosity. The greatest, most influential anti-imperial text ever written is the Book of Revelation, with its vision of the whore of Babylon. Babylon — which is Rome — is described as a city that is glutted on the wealth of the world, and its downfall is precipitated by the cutting of trade links that bring wealth into the city. So it’s very clear-eyed about the fact that the metropole is dependent on the links that it has with the outer provinces.

There are Romans who are extremely anxious about this, the most influential of whom is Tacitus, the great historian. Tacitus writes the biography of his father-in-law, Agricola, the governor of Britain. He describes how Agricola fostered the art of civilisation on the island: getting the natives to wear togas, to enjoy fine dining, to have baths. He says that the natives mistook these things as the marks of civilisation, when they were actually marks of their servitude. He is not writing this as a lecture in post-colonial studies. He’s not saying, “Oh, it’s terrible that we’ve conquered the Britons”. What he’s saying is that Britons are being seduced into the moral decrepitude that has already paralysed the Romans.

In Tacitus’s eyes, the greatness of the Empire is destroying everything that originally made the Romans great. That’s why he thinks Trajan is the best of emperors, because he’s embarking on all these brilliant conquests. He conquers the Dasians, then the Mesopotamians. But it all goes horribly wrong when Trajan, like so many others in Western history, invades Iraq. He pushes it too far. He has to pull the legions back out of Mesopotamia. It is then that he decides that Roman power has a natural limit after all, because the people beyond it don’t deserve the gifts of Roman civilisation.

This is why Hadrian builds frontier systems along the Empire, of which Hadrian’s Wall is the most famous. It’s not in any way an admission of defeat. It’s the equivalent of that enormous fence that they built around Glastonbury during the festival. It’s saying: “People on the inside, you can have a good time, hear Elton John and go glamping. But all you proles outside, you can’t come in.” That’s basically what Hadrian’s Wall is.

FS: Today a lot of people worry that we are somehow rather like the Roman Empire in its declining phases. There’s the sense that this world that seemed totally everlasting is crumbling and breaking. I was filled with hope reading your book because it starts with what feels like the end of the world — the chaotic Year of Four Emperors — and is followed by 100 years of peace. So maybe, we are in a moment more like AD 69 than the actual end of the Roman Empire. Does it feel to you like we’re on the downslope of a civilisation?

TH: I think we are going through a process of moral change that is more analogous to the Reformation than anything you get in Roman history. But I think that Rome provides us with a model: we are shadowed by the sense that if you have a moment in the sun, if you have greatness, then you are doomed as an empire to decline and fall. And I think the contrast is with China, an equally great empire in this period, getting very rich. Of course, over the centuries, China, as Rome does, will succumb to barbarians. The Chinese Empire will disintegrate, be reconstituted, disintegrate, be reconstituted, and yet, in a sense, always remain China. An entity called China endures.

We do not, in the modern world, have a sense of there being a land of the Romans, because that has long gone. And so I think that for us, probably far more than for people in China, there is the sense that golden ages are illusory, and that the greatest empire is merely a provocation, and that it will succumb and be destroyed. The lessons from the Book of Revelation and Edward Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire have fused to create a sense that you can’t be great in the long run. That is why the Roman imperial architecture of Washington, say, provides such scope for apocalyptic visions, because you just have to look at the Lincoln monument to think: “Oooh, your fall is coming, you’re doomed.” That is also, of course, what made the [January 6, 2021] Capitol riot so emotionally satisfying for so many people, particularly the shaman with his horns. It is hardwired into our minds that this is what happens to places that call themselves the Capitol. Barbarians do come, and the order collapses.

FS: I think now is a great moment to take questions.

* * *

Question One: How much credit can you give the emperors for Pax Romana? And how much was it just good timing and circumstance?

TH: That is a great question. Because of course, the emperors are the focus of most histories. And when you’re writing, it is quite difficult to get perspectives that are not centred on the imperial capital. I think that there are very few emperors who qualitatively affect the running of the Empire, and the course of events. Hadrian is one of them. So is Augustus. Augustus, I think, is the greatest political genius, certainly in the history of the West, and perhaps of all time. Reconstituting the imploding Republic; setting Rome and her Empire back on firm foundations; and doing so to such effect that, with the exception of the Civil War of AD 69, peace endures for essentially two centuries, and Rome as a world empire endures right the way up to the 15th century: that is a stunning, stunning achievement. No other emperor over the sweep of Roman history can rival that.

Hadrian is a significant figure — an emperor who stabilises the Empire by constructing what in effect is a frontier, although it’s not cast as that; by acknowledging the natural limits of the Empire; and, above all, by integrating the Greek world into the fabric of Roman imperial culture, so that in time we can talk of Greco-Roman culture. I think the next significant player is Diocletian, for his achievement in stabilising the Empire when it looks as though it might completely disintegrate at the end of the third century. And then, of course, there’s Constantine, his licensing of Christianity. So I would say that, between Augustus and the final collapse of the empire in the West, there are really only three significant emperors.

Question Two: There are centuries in between those figures. Who’s running the Empire then? Is it the deep state of Rome that’s in charge?

TH: The truth is that it’s the legions that are keeping it going. Without the legions, there is no peace. We tend to think of peace — Pax, the title of the book — as a slightly passive noun. But for the Romans, it’s very active. Pax is something that you impose at the point of the sword. It is maintained by the presence of legions, along the frontiers. These legions have to be paid for. And there’s a case for saying that the whole Roman Empire is an army with a piggy bank attached to it, the whole Empire essentially exists to provide the legions with the money that then enables the Empire to exist. “Legio” originally meant a levee. Every city in the ancient world, every tribal entity, had a levee of those men who were able to fight. A legion ends up something very different: a professional army, stationed where it has to be stationed. This is such an odd thing to have. And again, it’s the genius of Augustus that enables these to be set up. Without the legions, there is no Empire.

Question Three: Did women figure in the Roman Empire at all? Was there a woman behind the throne? Or were they really all very subservient in this period?

TH: Roman men have a kind of ambivalent attitude towards women in their families. Because, on the one hand, it is the role of a man to keep his subordinates in order, and women rank as subordinates. A paterfamilias has power of life and death over all his family. There’s no matriarchy in Rome. But having said that, historically, women have important roles to play in dynastic politics, that is the way that the Republic functioned. It depended on women going out and marrying other people, and then, if needs be, leaving them and marrying someone else. Their role, basically, is to stick up for their father and brothers; their husbands, by and large, are less significant.

Then, in the reign leading up to Nero, women become incredibly powerful, because if a man can have the blood of Augustus in his veins, then so do women, and that gives them a massive, divinely sanctioned authority. By and large, the men who are writing the histories are terrified by this. Think of the role that Livia has in I, Claudius, reconstituted in The Sopranos as the most terrifying mother perhaps in any drama. Messalina’s very name is a byword for sexual depravity. There’s Agrippina, the mother of Nero. These woman are portrayed in the histories as kind of terrifying predatory viragos. And that is a kind of tribute to the power that they have, in the wake of the extinction of the family of Augustus. (That power is obviously cut off and women again, certainly in the sources, start to play a more subordinate role.) I mean, you do not offend a powerful woman.

If you are lower down the scale, I think your life is pretty terrible. If you’re a slave girl, you are there to be raped. The Roman legal and sexual dynamics licenses pretty much perpetual rape if you are subordinate in a powerful household. I mean, the same is true for boys, but women are likely to be sexually abused throughout their life. And that is why Christianity is so radical, because Paul, when he’s writing to, say, the Romans of Corinth (Corinth is a Roman colony, so they’re culturally Roman to the Romans in Rome), he is saying to the male householder: “You are playing the role of Christ, your wife is playing the role of the church, therefore. That’s why you must have a monogamous, enduring relationship. Christ doesn’t go around raping the scullery maid. You mustn’t.” And that is the transformation that Christianity brings to sexual ethics.

Question Four: You talked a lot about the radical break that Christianity represented — the contrast with the extremely ruthless, pre-Christian, Roman world. Do you think there’s a case to be made, as I seem to recall Gibbon did, that Christianity was the ultimate example of the Romans getting soft?

That is what Gibbon says. And it’s also what Nietzsche says. Nietzsche says Christianity is a slave morality. I think actually the opposite. I think that the thing that enables people in the long run to continue feeling Roman, even when the sinews of government have been cut, and the imperial hold has gone, is that they retain a shared identity as Roman which has come to be fused with Christianity. And the reason that Christianity is so successful — the reason, if you’re looking at it in Darwinian terms, why it’s adopted — is that, in this period that Pax covers, this is a world that is full of different cultural centres. You can go and pay sacrifice to someone in northern Britain, or in Syria, and these are all gods. But in the long run, the heft of these cultural centres depends on them being local. I mean, as with the temple in Jerusalem, it’s the fact that they are local that matters. Christianity changes that.

The Christian people have no metropolis. This is what seems so odd to the Romans in the early years of Christianity. They are a kind of universal people — that ultimately makes Christianity so suited to an empire that is universal in scope: you can have churches, anywhere, and they’re all consecrated to the same God. So it doesn’t matter if it’s in Egypt or in East Anglia. And that enables a sense of being Roman to endure for as long as it does. So I think that actually Gibbon gets it the wrong way around. With Pax Romana, you get this extreme world, extreme development, a concentration of wealth, inequality increasing.

FS: The Gini coefficient.

TH: I have no idea what that is. Do I need to know what that is?

FS: A lot of people obsess about this — the gap between the very richest and the very poorest.

TH: The Romans didn’t care about that. In fact, if you were at the top end, they were all in favour of it. Roman society was founded on the principle that you defined yourself against the people who were below you socially. Right from the beginning, the Romans had an obsession with identifying where they stood in the social spectrum. They had a censor. A censor wasn’t someone who went around cancelling people or closing down newspapers; a censor was someone who, every few years, would go around, working out how much money each individual citizen had, and also his moral worth. And then kind of calibrating, and assigning them to a social class.

You could go up and you could go down. This really concentrated the mind.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/