It’s been 20 years since anthropologists announced the discovery of a new and exciting species of human, emerging from the mists of the urban jungle. This creature was best observed in its natural habitat of New York City: drinking a Grey Goose martini at a chic watering hole, pausing by a window to smooth his perfectly coifed hair, disappearing around a corner on feet clad in stylish moc-toe boots, leaving behind nothing but an unsettling sense of sexual ambiguity and the lingering scent of Axe body spray. What was he? A man, yes, but not just a man. He was an enigma wrapped in a mystery, equal parts fascination and mockery. Behold: the metrosexual.

For those too young to have witnessed the great metrosexual panic of the late Nineties and early 2000s, it’s hard to explain just how worked up we all were by the realisation that there were men out there who conditioned their hair and moisturised their faces and wore clothes that actually fit, and yet who were somehow — and here, the mind boggled — not gay. In 2003, “metrosexual” was Word of the Year; in June, it was subject to a writeup in the New York Times Style, under the winking headline, “Metrosexuals Come Out”. By December, it was showing up in everything from celebrity profiles to book reviews to think pieces pondering whether the metrosexual was definitionally metropolitan, or whether men in the suburbs could get in on this new brand of masculinity too. Threaded through it all was a sense of waiting for the other shoe to drop: the metrosexuals were into women, or so they said, but they obviously weren’t straight in the same sense as the cowboys, lumberjacks and plumbers of the world.

Like many Style-section pieces, the struggle to define the boundaries of metrosexuality was ultimately more about marketing than identity: “Along with terms like ‘PoMosexual,’ ‘just gay enough’ and ‘flaming heterosexuals,’ the word metrosexual is now gaining currency among American marketers who are fumbling for a term to describe this new type of feminized man,” wrote the New York Times. Then, as now, we weren’t quite sure how men should be; the metrosexual was an early hint that one possible answer was: more like women.

Today, metrosexuals are recognisable as an early prototype of affinity-based identities, the kind that describe how you present yourself instead of what you do (see: the straight-married women in their thirties who have never slept with a woman but self-identify as “queer“). Although some metrosexuals of the early 2000s dabbled in gender nonconformity — with painted nails and skirts and such — in a way that might now be referred to as “queerbaiting”, metrosexuality wasn’t ever really about who these men wanted to have sex with. It was about masculinity, and what that was supposed to look like, and particularly about how this new breed of man would be received by women.

As for this, feelings were mixed. For some women, perhaps the kind who perk up at the phrase “couples spa trip”, a metrosexual boyfriend represented the best of both worlds; for others, these men invited comparisons that tended to make us feel, if not unfeminine, then at least like slobs. In my early twenties, at the peak of the Metrosexual Discourse, I won a trip for two to a ranch in Texas after entering an essay contest in which entrants were asked to describe why their metrosexual boyfriends needed lessons in manliness. I gamely joked about how my boyfriend’s predilection for pink shirts and casual use of the phrase “mani-pedi” were becoming relationship dealbreakers, but looking back, what strikes me is that this was less about masculinity than a bad match. The poor guy didn’t need manliness lessons; he just needed a different girlfriend, ideally one who shared his interest in nail care.

But the is-he-or-isn’t-he jokes among women also masked a quiet sense of desperation. Most straight men had come to approach matters of grooming and culture with an aggressive indifference: an approach that flew in the face of historical norms. It wasn’t just that the metrosexual had an obvious precursor in the fashionable dandy of yore; being mannered and being marriageable had always gone hand in hand. Jane Austen’s eligible bachelors dressed for an occasion, and even the hyper-masculine James Bond was fussy about the cut of his tuxedo. But sometime in the mid-20th century, those associations began to shift, perhaps fuelled by a Sixties protest culture that recast civilised norms — things like haircuts and suits — as tools of oppression. The masculine ideal morphed from Cary Grant in North by Northwest to something far scruffier, unshaven and untucked.

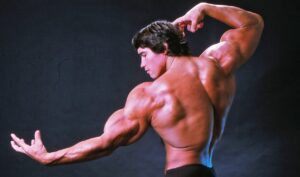

And once caring about your appearance became square, it was only a matter of time before it also became (homo)sexually suspect, culminating in the Nineties nadir wherein every sitcom couple included a schlubby man paired with an impossibly hot wife. Straight men asserted their straightness via a sort of peacocking in reverse: whoever wore the worst outfit was probably the most heterosexual. Not even the sexiest man alive could make these terrible clothes look good.

One can detect a confluence of factors at play here, including the downstream effects of tech replacing finance as the nexus of male power and influence. Suddenly, the biggest boss in the room wasn’t a Wall Street VP in a three-piece suit, but a gawky geek who had never been interested in clothes nor looked especially good in them. For these guys, disentangling basic male fashion and grooming standards from male sex appeal may have functioned as a sort of revenge — not just against the preppy bullies and jocks of high school, but against the oppressive notion that appearances should matter at all. At the same time, the increased visibility of gay men in elite cultural spaces — art, fashion, food — combined with the casual homophobia of the era to create a visceral sense that culture itself was “gay”, a word that became synonymous with “uncool”.

And so the heterosexual man of the moment was identifiable not only by his Seinfeldian pairing of ill-fitting jeans and chunky white basketball shoes, but by an adolescent distaste for anything more highbrow than a Die Hard movie. These guys didn’t dance, didn’t cook, and definitely didn’t care about art or films or music. If metrosexuality was about straight men who didn’t mind seeming a little bit swishy, it was arguably an overdue response to straightness having become synonymous with having the sartorial and cultural tastes of a five-year-old. At a moment when raunch culture was on its last legs but the soft boy had not yet made his debut, metrosexuals were like a gateway drug to a new, more mature, sensitivity-trained brand of masculinity.

And once men started to care what they looked like, a massive vibe shift ensued: more stylish clothing, for instance, meant slimmer silhouettes, which meant more time at the gym, which meant that metrosexuals were targets for not just fashion and grooming but fitness and nutrition products as well. We think of them as a sociological phenomenon, but as the New York Times pointed out: they were a marketing demographic first. You can practically see the dollar signs flashing in the eyes of a marketing executive quoted in the original writeup on this emerging category of man: ”The guy who drinks Grey Goose is willing to pay extra,” he said. ”He does it in all things in his life. He doesn’t buy green beans, he buys haricots verts.”

First you make a person believe that spending $40 on shampoo isn’t vain or frivolous; then, you convince him that actually, the shampoo is a form of self-care. This is the logic that has long persuaded women to spend hundreds if not thousands of dollars a year on skincare, makeup and beauty treatments; but it’s also a logic that persuades men to adopt the same neuroses women have long struggled with around fashion, aging, and physical fitness.

And persuaded they are: men are now seeking out tweakments in record numbers, and suffering from body dysmorphia at greater rates than ever before. TikTok “looksmaxxers” trade tips on proper skincare; Twitter accounts scold men for sartorial crimes like improperly matching a formal tie with a rugged sport coat. Caring about how you look has been fully recoded from a niche, suspicious twist on traditional masculinity to an obligation, as it has always been for women. The sexual suspicion surrounding men being effeminately preoccupied with their faces has disappeared. Indeed, a key tenet of looksmaxxing is that the young men who do it make themselves more attractive to women — and why not, when there’s no perceived paradox between wanting to be desired by women and wanting to behave more like them?

The past 10 years have not only encouraged men to adopt the same neuroses as women about what other people think of their skin and hair and bodies, but to constitutionally reorient themselves toward the feminine. Consider how often are men instructed that they need to be more feelings-oriented, less assertive, more empathic, less status-seeking — or how male sexuality, or even just sexual interest, is increasingly understood as inherently predatory and dangerous. Consider the 2018 American Psychological Association press release which declared that “traditional masculinity — marked by stoicism, competitiveness, dominance, and aggression — is, on the whole, harmful”, and all but announced the profession’s intent to wage war on manhood, one 50-minute therapy session at a time. Consider the summer blockbuster Barbie, in which the previously effeminate Ken’s newfound masculinity is presented as both a profoundly malevolent force and an absurd punchline.

Replacing old-school masculinity with metrosexuality may be the least objectionable way in which our concept of ideal manhood keeps tipping incrementally toward the feminine. Certainly, as a straight woman, I’m in no hurry to return to a time when men proved their heterosexual bona fides by competing to see who could dress (and sometimes smell) the most like literal garbage. But if boys and men are in crisis, as we are repeatedly and reliably assured they are, I’m also not persuaded that recalibrating the entire world toward a more feminine baseline is the best way to avoid that outcome.

The arc of the metrosexual holds lessons here: we have seen the backlash to a world in which being a man becomes synonymous with being a boor, but we have also seen what happens when that backlash curdles into a sense that masculinity and boorishness cannot be disentangled, and hence should both be rejected wholesale. In a culture that can’t conceive of healthy masculinity — a culture that instructs men that the best way to be is more like a woman — some men will conform. But others, finding nothing they can emulate and nothing to aspire to, will revolt — and it will be ugly.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/