As the UK limps into another recession, and with inflation set to rise again today, it’s hard not to conclude that Britain’s economic cognoscenti really don’t know what they’re doing. For years, we’ve been lavished with promises of growth, investment and impressive economic programmes — only for each to turn to dust.

It would be a mistake, however, to take today’s miserable news as yet more proof of a country on the wrong side of some arbitrary percentage milestone. The problem is bigger than that: concealed by our incessant focus on short-term inflation data are far more significant issues of economic management.

Last week, to no fanfare whatsoever, the Treasury Committee released an extensive report on a set of policies the Bank of England has undertaken over the past few years. The report’s immediate focus was on the Bank’s recent Quantitative Tightening (QT) programme, which promotes higher interest rates. But read properly, it was an attempt to assess Britain’s central bank policy since 2008. QT, after all, was a direct attempt to unwind the Quantitative Easing (QE) programmes that were put in place in response to the financial crisis. To judge its effectiveness, the report had to look at the Bank’s monetary policies over the past 15 years. Suffice it to say it made for damning reading.

In a capitalist economy, financial markets should have one job and one job only: the allocation of capital. They should look at various businesses and assess their viability. Those they assess as being viable should then access funding on good terms; those that are not viable should not.

But since the onset of QE, the City has largely become an arm of the Bank, constantly watching its every move for signals about what to do next. The reason for this is straightforward: the QE programmes have given the central bank almost total control over the government bond market, partial control over the corporate bond market, and a large degree of influence over stock prices. If you are an investor and you want to make money, the easiest way to do so is to guess what the Bank is going to do next.

There are, as a result, plenty of investment professionals consulted in the report, all of whom have firmly bought into the QE/QT framework. Each provides their own minor assessments: one will say QT is being undertaken too fast, another will say that it is being undertaken too slowly — and, at the end of the day, the Bank will fall somewhere in the middle. All very sensible, all very orderly. Until it isn’t.

In fact, what is so striking about these assessments is their lack of clarity. Beyond the fundamental virtue of the QE/QT framework, the only point that everyone agrees on is that they really have no way to know what is going on. The Bank, as the report makes clear, “is uncertain about the macroeconomic and money supply effects of QT”. Elsewhere, it notes that “the Bank is taking a ‘leap in the dark’ by embarking upon a major monetary operation without specifically and separately tracking its effects”. Indeed, at one point, the Governor himself admits this, explaining that such uncertainty is “why we keep QT under constant review”.

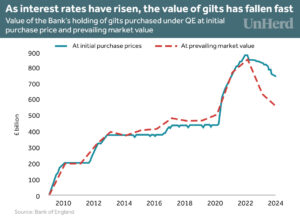

Of course, no policy undertaken by any government institution produces certain outcomes. But this, it’s worth spelling out, is the Bank of England, the very institution tasked with keeping the financial peace; indeed, its own independence rests on the pretence that they set monetary policy in line with scientific criteria. Instead, it’s been treating our economy like a roulette wheel — and one that will soon be stacked against us. As interest rates have risen, the value of gilts — government-issued bonds that are supposed to be low-risk — has fallen fast. You don’t need to be a finance whizz to understand what this gap represents: losses.

Indeed, these losses are shown clearly in the Committee’s report: “Annual losses in each of 2023 and 2024 will amount to £40 billion, eroding the cumulative £124 billion positive cashflow that was generated up until September 2022,” it states. Crucially, this doesn’t even take into account that these significant and rapid declines are dependent on optimistic forecasts of future inflation. If inflation remains stubbornly high or even rises again — say, on the back of ever-increasing geopolitical tensions — then the downturn will be even more significant. And who will pick up the bill? The Treasury and, via the Treasury, the taxpayer.

The Committee, understandably, were less than pleased with this: “Notwithstanding the operational independence of the monetary policy… it strikes us as highly anomalous that decisions have been and are being taken concerning huge sums of public money without any regard to the usual value-for-money requirements”. On the face of it, such an indictment surely calls for root and branch reform of the Bank of England. Its QE programmes of the past 15 years have been a disaster, turning would-be investors into dreary inflation-watchers. But beyond this, it has also wasted money — public money — and left the country effectively broke. The Bank of England knows this; it is, after all, what they told Liz Truss when she tried to force through tax cuts.

Yet while the Bank is more than happy to aim their budgetary fire at a sitting Prime Minister, they seem a lot more reluctant to address how much their own monetary policy experiments have cost the country. No doubt this will be forgotten amid today’s inflation news. Politicians will blame each other, the bankers will sternly warn that we are living in “hard times”, and the national press will lap it up. And missing from all this will be any mention of the real culprit: the Bank of England itself.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/