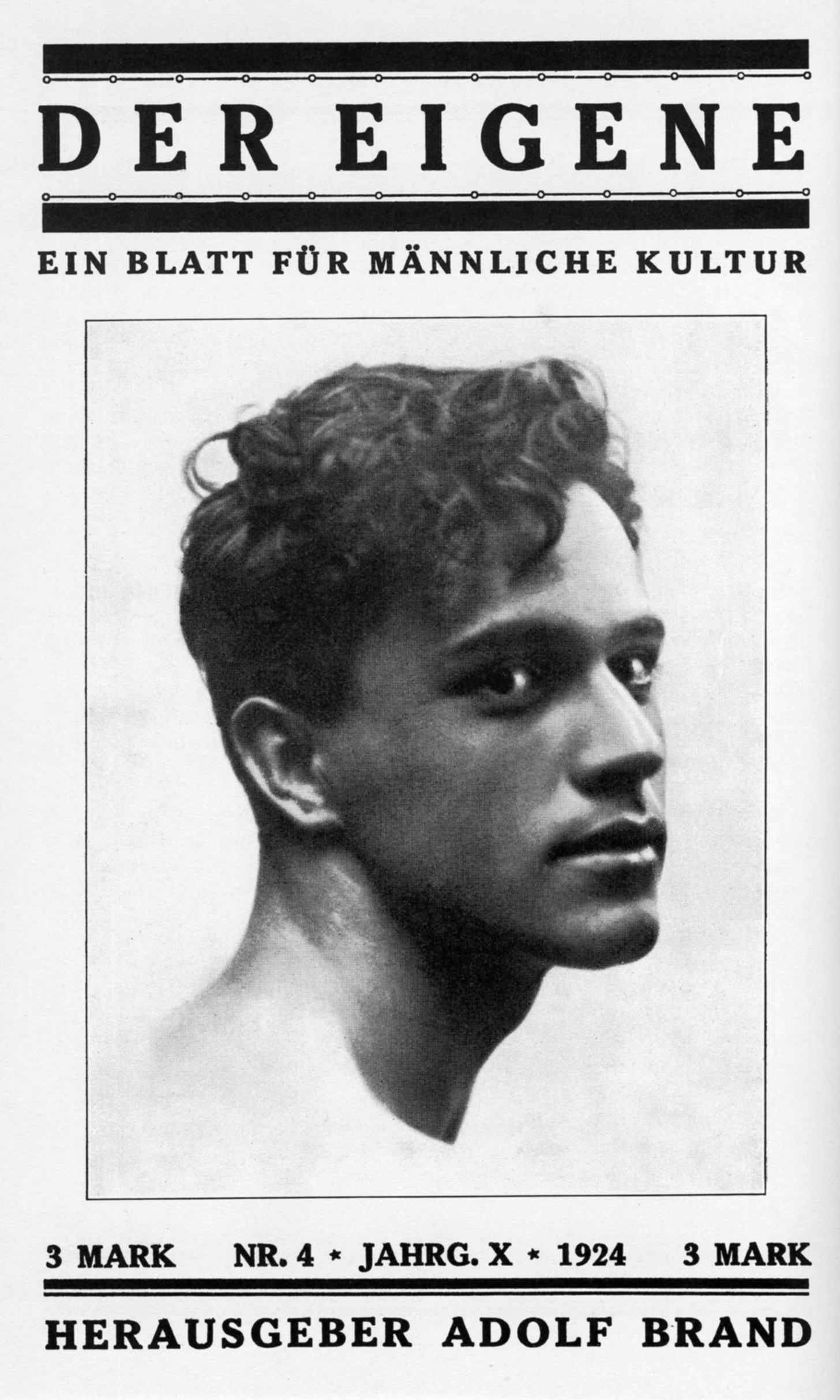

The gay liberation movement didn’t begin at the Stonewall Inn in 1969. Nor, for the record, was it started by a black trans woman. In fact, movements for the decriminalisation and acceptance of homosexuality have their origin in a loose group of thinkers, scientists and artists in fin de siècle Germany, the most interesting of whom clustered around Der Eigene. Published from 1896 to 1932, it can claim the accolade of being the world’s first gay journal.

The concepts of “homosexuality” and “heterosexuality” didn’t actually come into being until the late 19th century. As soon as they did, people who were homoerotically inclined were compelled to consider the meaning of their desires, where earlier generations might have simply acted on them. For the followers of Der Eigene, who were predominately men, homosexuality was best understood not as an identity — as we now understand it — but as a form of refined taste, and an extension of male friendship. In a kind of “manifesto” for the journal, its founder Adolf Brand wrote that he strove for, “beside the sense of female beauty, also the sense for male beauty, and by again setting friend-love beside woman-love as having completely equal rights”.

As with later gay liberation movements, the first gay rights groups were motivated more by shared enemies than affinities. In Germany at the time, many widely different groups were united in campaigns to repeal Paragraph 175 of the German Criminal Code, which criminalised sodomy. But homosexuals differed greatly in their conceptualisation of homoerotic desire. The intellectual strand most opposed to the ideas of Der Eigene, followed the physician and sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld and his Scientific-Humanitarian Committee who pioneered the idea that homosexuality (and transsexuality) were an innate condition traceable to biological cause. Gay people, in Hirschfeld’s view, were a “third sex” whose hermaphroditic nature gave rise to unique differences in attitude and behaviour. While these ideas have evolved greatly over time, we can hear echoes of Hirschfeld in the supposedly progressive scientific obsession with biologically classifying those who are sexually diverse, leading to the questionable notion of “gay genes”.

For the homosexuals who wrote and contributed to Der Eigene, which included many prominent men of the day — including political journalist Kurt Hiller and the novelist Thomas Mann — all this talk of an inherent hermaphroditic soul was ahistorical and wrongheaded. From Greek antiquity to European aristocracy, they argued, sexual acts between men could be seen as a natural extension of passionate male friendship. To describe this worldview, artist and scholar Elisar von Kupffer coined the term “Lieblingminne” in Der Eigene, combining the virtues of Freundesliebe, love of friends, with Minne, chivalric love.

Many German homosexuals were inspired by von Kupffer’s collections of homoerotic literature, which highlighted that same-sex desires had been felt by many historically-significant figures, from Zeno of Citium to Alexander The Great to Michelangelo. Rather than supporting Hirschfeld’s theory of innate homosexuality, this was seen as key evidence against a medical model. As sexologist Benedict Friedländer, wrote in Der Eigene:

“[To accept Hirschfeld’s view] in ancient Hellas in particular most of the generals, artists and thinkers would have to have been hermaphrodites. Every people from whose initiative in all higher human endeavours every later European culture fed must have consisted in great part of sick, hybrid individuals.”

For the contributors to Der Eigene, it seemed only natural that strong male friendship would occasionally incorporate an erotic component. But for them, sexual desire was culturally contingent: homoerotic desire has waxed and waned over time, driven by the sentiments and spirit of the age. Dutch author Peter Hamecher wrote in the journal that, “I altogether hold the sexual instinct, in all its apparent determinacy, to be something very intangible, something swinging back and forth between extremes”.

Male friendship was particularly sentimental in the 19th century. Expressions of love between friends bordered on the outright romantic — the letters exchanged by Abraham Lincoln and Joshua Speed being a prime example. Given the gender segregation in many aspects of life, and the strict heterosexual courting rituals, sexual contact between young men was also relatively common. It was in cultures which prioritised beauty, whether physical or spiritual, that the homoerotic sentiment was most cultivated in the wider population.

The decriminalisation of homosexuality, for Der Eigene, was therefore not about protecting a minority, but rather invigorating Germany’s potential for homoeroticism. The journal’s ideals were tied closely to naturist movements of the time — focused on nudism, bodybuilding, and co-existence with nature. Homoeroticism is presented as a way to raise oneself above the pedestrian, bourgeois ideals of industry and production.

Contemporary LGBT scholars are often quick to dismiss Der Eigene as “masculinist” in orientation and even “proto-fascist” in its aesthetics, despite the fact that the journal was a target of Nazi purges. Professor Andrew Stewart from the University of Toronto caricatures Brand’s ideas as calling for a racially pure, bisexual Ubermensch to replace the tainted, effeminate homosexual:

“The importance of physical health and fitness, hyper-masculinity, and white supremacy find modern parallels in the experiences of some queer people of colour, trans people, and others who do not achieve the standards of beauty as set by a white, cisgender, and masculine gay culture.”

These accusations aren’t entirely baseless. Brand and Friedländer were not what we would now call “intersectional”. They criticised early feminist movements, viewing women’s calls for men to take greater responsibility for family life as being contrary to the journal’s goal of re-establishing a homoerotic male culture. Further, unlike the early Swiss gay journal Der Kreis, which they inspired, Der Eigene rarely published lesbian writers.

Nevertheless, it would be unfair to throw out the unique perspective of early gay rights activists, merely because some prominent members had outdated views — especially because their views were not universal across Der Eigene. Frequent contributor Edwin Bab held strong feminist sympathies, writing:

“I assert that there is no difference between man and woman in the psychic and intellectual characteristics … only our customs, which make every productive activity highly difficult for the woman, are to blame for the fact that the number of productive women is relatively small.”

Attempts to connect the journal to National Socialism are even more spurious: Brand, who leant Left politically, was never a supporter of the Nazi Party and was highly critical of homosexual members such as Ernst Röhm, calling him a “hypocrite and a traitor”. However, as scholar Harry Oosterhuis has pointed out, Brand was not as discriminating as he should have been when publishing people who criticised Hirschfeld — who, it should be noted, was Jewish. He ran an article by Röhm’s friend, the Nazi Karl Günther Heimsoth, who gave us the phrase “homophile”. Heimsoth criticised Hirschfeld, Oosterhuis writes, by “asserting that the ‘homosexual feminism’ of the ‘Jewish Committee’ was dangerous to the ‘German eros’”. And, Oosterhuis goes on, “instead of refusing the article or expunging the anti-Semitic phrases, Brand only wrote a preface stating that he did not agree with all of the author’s views”.

Nevertheless, Der Eigene is forgotten today less because the original contributors are deemed “problematic” than their views on homosexuality running counter to how modern gays and lesbians have been taught to see themselves. That one is “born this way” is a key pillar of contemporary LGBT thinking. But in the pages of the first gay journal, sexual desire is better conceptualised as a taste — an appreciation of beauty cultivated through early experience and culture. One is not born homosexual (or heterosexual) but with a capacity to perceive aesthetics; over time, this capacity, combined with experience, shapes sexual preferences.

Despite now being lost to time, these ideas still had currency amongst mid-20th century gay rights activists both in the US and Europe. For example, American gay activist Carl Whitman’s influential 1970 “A Gay Manifesto” notes that:

“Homosexuality is not a lot of things. It is not a makeshift in the absence of the opposite sex; it is not hatred or rejection of the opposite sex; it is not genetic; it is not the result of broken homes except inasmuch as we could see the shame of American marriage. Homosexuality is the capacity to love someone of the same sex.”

Michel Foucault also echoed the goals of Der Eigene in his comments during an interview with The Advocate 1984, where he notes: “I think what the gay movement needs is much more the art of life than a science … Sexuality is something that we ourselves create — it is our own creation, and much more than the discovery of a secret side of our desire.”

While some contemporary “queer” academics take up this anti-essentialist mantle, they do so without appreciating homoerotic desire as a beautifying force. Theorists such as Lee Edelman are quick to frame homosexuality as inherently “transgressive”: the Freudian death drive in opposition to procreative sexual desire. The contributors to Der Eigene, however, understood homoeroticism as constructive — a practice that encouraged healthy and flourishing individuals. Whereas today’s nihilistic queer theory is libertarian, Der Eigene’s was restrained. “Every sexual excess and every sexual dissolution is of course decidedly to be advised against,” wrote Brand in one of the journal’s early issues.

Rather than advocating a full liberation of desire, contributors to Der Eigene often expressed concern about, say, the effects of excessive masturbation, the spread of venereal disease, or the predatory behaviour of men towards young women. Homoeroticism was seen as a cure for the social ills of male sexual desire run amok.

It’s a shame that this view of homosexuality, as neither fixed biological orientation nor “radical” disruptive force, has been forgotten. Key victories in gay rights have not given way to a “post-gay” moment of self-reflection for those who feel predominantly same-sex desire see themselves not as “other” but as universally human. Instead, we see a doubling down of identitarianism, particularly online, where every kink, feeling and sexual experience is ripe for categorisation. The New Left notions of “authenticity” and “finding oneself”, which shaped early gay rights movements have evolved with the internet into what philosophers Hans-Georg Moeller and Paul J. D’Ambrosio call “profilicity”, where one’s identity is a process of obsessive self-marketing. There are now labels for those who want both love and sex (demisexuals), who prefer just masturbating to porn (technosexuals), and who don’t like having sex at all (asexuals).

The brilliance of Brand and the other contributors to Der Eigene was that they could move beyond the delusions of sexual identity, while advocating and defending homoeroticism. The group tackled moralist tirades that equated same-sex desire with degeneracy by pointing to the historical and aesthetic evidence that cultures of homosexuality and cultures of greatness were one in the same. It’s precisely at this current time of sexual hysteria, when intimacy has been declared dead and queer theory diffuse, that our current paradigms of homosexuality should be questioned — and we should look to the past to inform our sexual future.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/