A decade ago, I rewatched Gladiator in a freezing cold forward-operating base outside Mosul with Kurdish Peshmerga, cocooned in brightly-coloured blankets. When I complained that the sound wasn’t working on the small television, someone replied “Surely you must know every word?” and he was right: I did, and so did everyone else there. There are few modern films of which this could be said, and at times it seems Sir Ridley Scott made all of them. Gladiator alone is arguably the last of the mass market blockbusters to have achieved both critical acclaim and global cultural currency, a conscious homage to the golden era of Hollywood epics. From Bladerunner to Alien, Black Hawk Down and Kingdom of Heaven: Scott is a master of the genre movie, creating sumptuous film equivalents of what Graham Greene called “entertainments,” thrillers with an aesthetic or philosophical edge raising them far above the medium’s simple demands.

And yet, as shown by the almost fearful anticipation over his biopic Napoleon, Scott’s output is wildly variable in quality. When he produces a dud, such as Robin Hood or Exodus: Gods and Kings, it’s a real stinker, both leaden and bombastic, the filmic equivalent of a bloated rock band’s cocaine grandiosity. Yet Scott seems immune to external criticism. “I have no favourite film of mine,” he declared, “they are all my favourite children, and I have no regrets about any one of them. At all.” How are we to understand this strange duality? Is he a great director who occasionally makes bad films? Or is he fundamentally a studio hack who somehow makes great films? Is Scott the greatest bad filmmaker of all time?

Critics most frequently liken him to a great general, marshalling vast crews and controlling every aspect of production with a logistician’s eye; he sets up workshops to produce armour and uniforms and takes over North African cities like an occupying force. There is no other filmmaker so seduced by the thrilling spectacle of vast armies on the march, the glitter of sunlight against swords and spearblades, and the brightly coloured splendour of battle standards flapping against the wind. Even Isis, who had an eye for such things, felt compelled to steal battle scenes from Kingdom of Heaven for their propaganda videos. In Black Hawk Down, every soldier’s death is as abrupt and brutal, yet as lovingly detailed, as that of a warrior in the Iliad who is mentioned only to die. Scott takes an honest, boyish pleasure in war: his enthusiasm sweeps the audience away in all its glory and adventure like a recruiting sergeant’s drum.

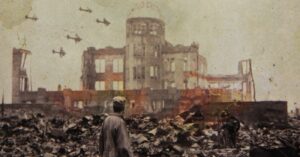

The young Scott was shaped by war; his earliest memories are of sheltering in an understairs cupboard from the Blitz. Scott credits his father, a Royal Engineers brigadier who helped design the D-Day Mulberry Harbours, for imposing a sense of productive discipline within the family: “His whole mindset on simplicity and order and reliability, I guess set into me. It’s part of my upbringing, part of my schooling.” The young Scott lived in British-occupied Northwest Germany, attending school in a converted Kriegsmarine barracks where every morning he would walk past a fleet of tethered U-Boats, cocooned in plastic. Did this mark his filmmaking style?

Certainly, there is no other director who can combine boomer liberal morality with a sense of scale and grandeur edging on the fascistic: for his vision of Gladiator’s Rome, Scott studied Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will and Olympia, and the Tyrell Corporation offices in Blade Runner resemble a ziggurat furnished by Albert Speer. His 1984 advert for Apple — in which he employed shaven-headed National Front “connections” as cheap extras — is an early iteration of this seductively totalitarian aesthetic. Even the proto-Indo-European speaking, marble-white Greek statue-like aliens of Prometheus and Alien Covenant strangely prefigure the aesthetics of the modern internet dissident Right.

Yet instead of a general or a Caesar, perhaps we ought to think of Scott as a great British industrialist, who in an earlier time would have built great steamships and chains of factories. A product of what was rapidly becoming the post-industrial Northeast, Scott was shaped by the looming shipyards of South Shields and steel mills of West Hartlepool. His mother was a miner’s daughter. “All around us was darkness when we were younger — rain and the industrial moors. That’s where Ridley got Blade Runner from,” his brother Tony remarked, and indeed the film’s opening shots, with jets of flame roaring from tall furnace chimneys, are a direct reference to Hartlepool’s now-lost industrial grandeur.

“There were steelworks adjacent to West Hartlepool,” Ridley remembers, “so every day I’d be going through them, and thinking they’re kind of magnificent, beautiful, winter or summer, and the darker and more ominous it got, the more interesting it got.” His first creative work, the 1965 short Boy and Bicycle, transposes the style of the French New Wave to the grey industrial landscapes of the Northeast, the “cancerous coast, tumours of industry”, as his narration calls it, where you “breathe through nasal fuzz at all times” — an early artistic vision reimagined, for commercial purposes, in the sentimental brass-band proletarian nostalgia and sepia soft focus of his famous Hovis advert. His art school background, and struggles with studio executives who butcher his vision, obscure this driving fascination with work and industry.

Another director might have transmuted these elements into tiresome gritty agitprop, but Scott is himself an industrial machine, perhaps the last of the Victorian capitalists in all their grandeur. “I’ve got three corporations. And I love business. If I hadn’t been a filmmaker I would have stuck with business,” he has stated, “I’m pretty working-class in that sense, I was never a child who saw a guy in a Rolls Royce or a Bentley and thought ‘Fuck you.’ I always thought: ‘I want one of those one day,’ and that was it.”

Like no other Hollywood director, Scott is absorbed by the world of work, and the mechanics of engineering. His crusading hero Balian is a blacksmith, whose greatest happiness is found teaching his new Arab serfs the magic of irrigation. The spaceship Nostromo in Alien is a working vessel, a “commercial ship”, cramped and grimy with a working-class crew, leaking oil and lubricant. Its occupants smoke endlessly and grumble about their poor food, and their salvation is found through understanding the internal workings of the ventilation system: they may as well be hauling coal through space. Alien’s world is a radical, industrial upturning of the pristine and coolly detached futurism of his idol Stanley Kubrick’s 2001. Even the God-like aliens of Prometheus are — like Scott’s father — “Engineers.”

Interpreting Ridley Scott as a titan of British industry, we also understand his failings. Just as Britain’s extraordinary inventiveness rarely translates into industrial power, Scott essentially creates new genres from scratch, yet discards them to be elaborated on and commercially exploited by others. In Blade Runner, he invented Cyberpunk, in Alien, the spaceship Gothic of any number of later sci-fi films, just as the immersive, confusing soldiering of Black Hawk Down made HBO’s later, more commercially-acclaimed Generation Kill possible. Though he is interpreted now as the greatest journeyman director of the Hollywood studio system, Scott is then, in both his strengths and weaknesses, a perfect exemplar of the British creative genius.

When he moved to Hollywood to make 1981’s Blade Runner, set in the dark dystopian future LA of 2019, he not only brought Hartlepool’s industrial landscapes but its weather, insisting on relentless, driving rain in every shot: “When they asked me, ‘Why is it always raining outside?’, I said, ‘Because that’s how I bloody want it!’ ” Back then, this most Hollywood of directors was seen as possessing a dark, European sensibility quite alien to the sunny optimism of his new workplace. “I was born in drizzling rain in the northeast of England,” he has stated, adding with emotional truth if not historical accuracy that “The northerners are the Celts, and they are all nuts. It’s a Celtic thing, you know you tend to be a bit ‘the glass is half-empty’ rather than ‘the glass is half-full.’” Perhaps his most perfect film, Blade Runner, is a deeply pessimistic dream, a world where technological advance is paired with scarcity rather than abundance, and the only desirable future is “off-world”. Buildings are damp, everything is old and shabby, a vaguely-defined sense of doom and decline looms over the dirty city he is, as I say, a product of Britain.

In Blade Runner, too, all communication is abrupt, clipped speech filled with strange non-sequiturs, all emotion proved to be false. “As an Englishman, I’m aghast at emotional intensity,” he has remarked, adding in a later interview that “In film, it’s very important to not allow yourself to get sentimental, which, being British, I try to avoid. People sometimes regard sentimentality as emotion. It is not. Sentimentality is unearned emotion.” Like Graham Greene’s own entertainments, Scott’s films all display this certain English “sliver of ice in the heart”.

A cynical Briton in Hollywood, Scott’s career fated him to work in the ideological dream-factory of the American empire during both its rise to global dominance and its decline. What is the message of Gladiator, after all, but the realisation of a decent, taciturn provincial that the empire is corrupt at its core? In Black Hawk Down, what could have been a Jerry Bruckheimer flag-waving schlockbuster showed a 9/11 audience imperial overstretch at bloody ground level — its lesson that military intervention in a troubled Islamic world, even if noble, is futile was apparently lost at the time: even Donald Rumsfeld attended its first screening. Kingdom of Heaven, contemporaneous with both the Iraq and Afghanistan wars and the New Atheist movement, made the implicit explicit, providing a heavy-handed rebuke to both Western crusading zeal and organised religion (and a corresponding, perhaps overindulgent vision of Islam that caused controversy at the time).

We might say there are two Ridley Scotts, expressed in the colour palettes that have come to dominate his later films: a Ridley Scott of greys and blues, of toil and depression and the cold and hostile northern landscapes of Prometheus and Alien Covenant, and the expansive golden-hued Ridley Scott of exotic spectacles, as opposingly bright and filled with adventure and opportunity — yet ultimately alien — as Hollywood is from Hartlepool.

As Scott ages (at 85, we may expect Napoleon to be among his last films) the palette of his films has darkened along with his themes. The questions of the dying industrialist in Prometheus — “Where do we come from? What is our purpose? What happens to us when we die?” — now reflect the anxious preoccupations of a master approaching the end of a long and illustrious life.

To argue over his value as an artist is to misunderstand his cultural place. A product of the Anglo-Saxon imagination, displaying both its nose-down dogged devotion to hard graft and its paradoxical accompaniment, the yearning desire for expansive new worlds to conquer, Scott has achieved both. Like the landscapes that formed him, he is both a relic of Britain’s industrial heritage and a vision of worldly success. Whether he is an auteur or merely an industrious craftsman is beside the point. Like Maximus, he gives the crowd what they want with ruthless efficiency and they love him for it. Are you not entertained?

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/