Audrey Diwan’s Happening, which won the Golden Lion at Venice and has a “100% Fresh” score on Rotten Tomatoes, is as lauded as a film can be. Whether the appearance of acclaim makes this — the latest entry in the genre of prestige, festival-circuit abortion drama — a good film is a different matter.

Much has been lost in this cinematic adaptation of Annie Ernaux’s autofiction L’événément (2000). However, one mourns little. That slim book largely consists of self-indulgent and painfully predictable reflections on l’événement of l’écriture. Across her curiously prolific output of almost identical autofictions — punctuated by a few, mostly early, highlights — the author’s 1963 abortion holds especial place as the subject of not one but two texts: her début Les Armoires vides (1974) and its tedious reprisal, the source material for the present adaptation.

In brief, Ernaux, the daughter of a Normand grocer, the first person in her family to attend university, is a few months from graduation when she becomes pregnant by a bourgeois student from Bordeaux. Having the child will, she believes, doom her dreams of finishing her education and becoming a writer. In the months that follow, and with no help from the father, she desperately pursues a back-alley abortion; she finally ends up finding a marmish hospital nurse who performs such operations—for 400 francs—in her Batignolles apartment. Her procedure lands her in a hospital after dangerous haemorrhaging, a near-death experience without which, she tells us in the last pages, she wouldn’t have wanted to ever be a mother.

One can safely guess why Happening is considered good: it is “urgent” and “timely,” as we have been helpfully informed by critics everywhere. The film received its US release by IFC films on May 6, three days after the release of a draft ruling penned by Justice Alito, in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organisation, which would overrule Roe v. Wade. One could not have prayed for better timing.

Before that leak, director Diwan was questioned — particularly, by potential financiers — as to whether her film had any real social urgency. Indeed, in February, the French parliament extended the legality of abortion from 12 to 14 weeks after conception, despite fleeting opposition from Emmanuel Macron. Whatever timeliness might have been lacking in the French release, the stateside one has now been ensured a rapturous reception, a felicity not lost on the director: the screening I attended was preceded by a brief recording of Diwan and lead actress Anamaria Vartolomei stating that the film was of imperative importance, given these times we find ourselves in, that if we did not understand what illegal abortion was like, it would be impossible to preserve the right to legal abortion, et cetera.

It’s as simple as that: the point of this film is to show an illegal abortion, so that one might be convinced to support the right to legal abortion. This is of a piece with a pretty popular middlebrow idea of the role of art (see this much-cited study demonstrating fiction’s power to create “empathy”.) And yet, it’s hard to imagine this film convincing anyone who is currently against, say, the legacy of Roe to really change their tune; as I understand it, most of those who want Roe repealed subscribe to a contestable but fairly simple chain of inference: life begins at conception, therefore killing a foetus at any point is murder. Murder is immoral, and immoral things must be illegal. Thus, killing a foetus at any point must be illegal.

This calculus doesn’t provide much room for manoeuvre, and the presumed Dobbs opinion, for example, doesn’t partake of the harm reductionist logic behind this sort of scare-tactic filmmaking. The only person for whom a film such as Happening could move the needle is, I guess, an anti-Roe person who hasn’t realised that back-alley abortions direly endanger the lives of the women who receive them (does such a person exist?). And is that exceptionally sheltered pro-life person, if she does, going to be watching a French art film?

More likely, Happening is an example of preaching to the choir, and there, I wonder whether it might defeat its own purpose. After all, many rallying cries to Americans around abortion rights relate to incursions on the right to end pregnancy in the second trimester; for example, the Mississippi law at issue in Dobbs bans abortion after the 15th week, i.e. almost four months into pregnancy, and, one might note, after well over 90% of abortions are actually performed.

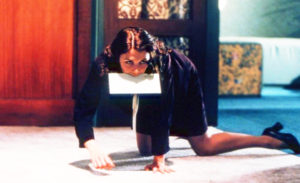

In Ernaux’s memoir, when the foetus is finally expunged after the insertion of two illegal probes, the narrator recounts that “a baby doll” falls out of her; the film is just as gruesome, showing the lead actress hunched over a toilet, red-faced and sweaty as what is visibly a child dangles from her and she breathlessly begs her bourgeois hallmate to cut the umbilical cord.

Your casual abortion advocate might not tend to think, when she contemplates laws like that Mississippi one, about the fact that a late-second trimester foetus has foetus has fingernails, limbs, etc. Is this scene actually going to make anyone support abortion rights more? This is one problem of the illegal abortion genre — the harder to procure an abortion, and the riskier it is, the more awful the actual act appears.

What about that scene in the notable 2007 Romanian film 4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days (a far more original work) in which the abortionist warns the woman not to throw the foetus, “whole or in pieces” in the toilet, which it’ll clog up, or outside, where dogs might eat it? Perversely, some might leave the movies newly doubting the trimester-viability-undue burden framework of Roe v. Wade (as modified by Planned Parenthood v. Casey). And perhaps they might not come out supporting, say, the Democratic bill enshrining Roe and Casey, a bill so expansive that, say opponents like Sen. Susan Collins, it might preempt state bans on even sex-selective abortions.

Happening isn’t a film to change minds — it’s about rallying the troops to protest, vote, or at least make some targeted political donations — but one should wish for more from their art than a Pavlovian bell. One might wish to experience the uniqueness of a human experience, or something of the sort. Instead, despite what Indiewire may have protested in its Sundance review, this film is squarely didactic, with dialogue so implausible and condescending as to almost insult the audience: Girl to doctor who refuses to perform abortion: “I want to continue my studies; that’s the most important thing for me.” Doctor to Girl: “No scandals in my office!”; Girl: “I would like to have a child one day, but not instead of a life; I would hate the child for that!”; Proud teacher to student, after she has an abortion and resumes performing well in class: “Have you been sick?”; Student to proud teacher: “Yes, with that illness that only affects women, and turns them into housewives!”

The message here is that Anne is a “brilliant student” who must have an abortion to preserve that career. But her brilliance is alluded to by gestures so heavy-handed — a facile lunchtime conversation about Camus and Sartre (“Camus really pierces you — Sartre, it’s more complicated!”); watching her friend teach her how to masturbate (a scene not in the memoir) with a Sartre poster in the background; raising money for the abortion (a scene not in the memoir) by selling, inter alia, Sartre’s Le Mur for 3 francs — that one can do little more than laugh. Given that the price for Anne’s literary career is a dangerous abortion, one might wish the output to be a little more impressive.

This cinematic Anne is far from a captivating character, far from a reflection of a complicated young woman, far from a figure to remind one of women’s need for self-determination and their infinite capabilities. She is simply a boring, paint-by-numbers “smart girl,” one among many predictable indicia that this is an “art film” (handheld camera, lens flare, and — it’s European — a lot of nudity). Despite all the laudatory reviews and Diwan’s discussion of her portrayal of “silence” in film, it unfortunately remains the fact that having a lead actress with large eyes, and a screenplay full of short lines and pauses does not a meaningful statement make.

Instead, Diwan’s film is ultimately so withholding as to say, well, nothing. The AV Club has hailed this film as “life-affirming”; but one wonders what there is to affirm, since our lead does, well, nothing besides look for an abortion and go to bars to talk to pretty unappealing men. In comparison, the scenes of the horrible, claustrophobic fate awaiting her — her parents listening to the radio and eating and laughing together — don’t seem half-bad.

I suppose this is a central failure of “the abortion film”. A director of any intelligence — and in this category, I include both Diwan and Eliza Hittman, whose Never Rarely Sometimes Always (2020) was something of a let-down after her earlier triumphs — is attuned to the reality of sex for the very young and not-rich woman, to the ways her desire to have sex is far from the entirely free, unbounded, pleasure-driven free-for-all conservatives often imagine and vilify. Rather, fornication is often a quietly humiliating and disappointing compromise, whose pay-off for girls is far from clear. But the young women of these films have almost nothing to celebrate. Agit-prop can be exuberant; one watching an East German film, for example, might sober up into clarity, but at the time feel completely transported by the dream of worker solidarity. But despite online calls to “shout your abortion”, obtaining an abortion isn’t actually a moment of joy (indeed, the idea it is plays into reactionary fantasies of gleeful abortion-on-demand). Nor, in these films, does fornication seem worth fighting for.

Art about sexually “immoral” young women can be profound; take Maurice Pialat’s A nos amours (1983), or Andrea Arnold’s Fish Tank (2009), which Diwan told her actors to watch. In those films, we care about the constraints on the young women at their centre precisely because their lives are not mere suffering; these are lives full of the joy and chaos of sex and the ecstasy of dancing and the shock and wonder of becoming, with whatever infirmity, an adult. These films treat their audiences like adults deserving of characters, not mere symbols of good and bad, and worthy of art, not mere homages to the audience’s own virtue.

No one may permit themselves to voice any of these misgivings. A film like this demands its accolades, assuming the right political boxes are ticked — and no one will seriously question whether that box-ticking achieves anything. For a film so uninventive and so empty, it’s astonishing that the most criticism it has had is a timid observation from the Washington Post that since we know this is a memoir by someone who, obviously, survived, “the nerve-racking nature of the events depicted is somewhat mitigated”.

That’s an understatement. The film develops no character, inhabits a gratingly artificial time capsule, and engages only in the most sophomoric political reflection. What does one really gain from seeing it? Neither entertainment nor edification. But by sitting through this and subsequently remarking on its “urgency” and “timeliness”, one gains a tidy bit of proof that they’re a very good person.

“In these times,” then, Happening’s critics are hamstrung.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com