The sun is beginning to set over the Donbas front line, and I’m hurtling down hedgerow-lined roads eerily reminiscent of English country lanes at 100km an hour, bouncing around in the back of a civilian SUV spray-painted dark green as the burly fighters in the front neck cans of Monster and buckle on their tactical helmets. We’ve entered the grey zone, the no-man’s land of abandoned villages and contested territory in the steppe landscape of eastern Ukraine; as we enter a stretch of road where the hedgerows thin out, making us visible to the Russian positions on the nearby hillside, the driver accelerates and screeches down the road until we’re safely back in the cover of the trees.

The platoon commander, “Pedro” — soldiers here all use noms de guerre, a tradition drawn from Ukraine’s long history of resistance to foreign occupation — turns to me, nodding at the treeline at the edge of the field. “That’s it,” he says. “This is the closest road I can take. The Russians are behind those trees.”

We park, reversing the SUV under an oak tree to keep it hidden from Russian drones, and hurry, crouching through the long grass, to the mortar section. The steppe landscape of the Donbas region is rippled with folds and gullies; the copses of tall oaks that have taken root in these shallow nooks provide perfect cover for guerrilla war, an archipelago in the endless sea of grass and ripening wheat. The mortar team have been concealed here for two days, in a tiny salient almost fully encircled by the Russian advance, observing enemy positions with their quadcopter and getting ready to strike.

Pedro points at a white house about a kilometre away at the edge of the Russian-held town of Svitlodarsk. It’s the Russian base. “Our Intelligence found a location with Russian mortar positions and an ammunition dump, so now the plan is to go, prepare the mortar, fire and leave immediately,” Pedro had told me as we were leaving. “With a quadcopter you can find a position to hit in 20 minutes — but once we fire, it will only take the Russians a couple of minutes to find our position and return fire.”

It is strangely tranquil, lying in the long grass fragrant with wild herbs, listening to the cuckoos and the rustle of the oak leaves — until the radios crackle and the mortar squad shout out their orders. Now. In just a few minutes of furious activity, the 120mm mortar belches out a dozen rounds in bursts of flame, as the quadcopter operator sits cross-legged in the grass, ordering them to adjust their elevation, then grins at his tablet screen as the rounds land directly on the Russian position.

Then it’s time to go: we race to the SUV and drive off at high speed, bouncing over bumpy dirt tracks until we reach the village road, as the retaliatory Russian artillery rounds land harmlessly on the road behind us. Pedro lights a cigarette, watching the road anxiously until the mortar squad join us in their pick-up truck.

Today was a good day for Pedro. He’s brought all his men back unharmed from another mission, and the target was destroyed. The following day, Pedro, who has an ongoing social media feud with mercenaries from the far-Right Russian Wagner Group on the other side of the frontline, in which they threaten to kill each other, would show drone footage of the Russian soldiers in their trenches getting obliterated by his mortar fire on his phone, overlaid with a death metal soundtrack and cry-laughter emojis. Welcome to war in 2022.

I spent a week in rural Donbas with Pedro’s platoon, fighters from the Ukrainian Volunteer Corps or DUK, the militia of the nationalist Right Sector party, on their first mission since they were formally absorbed into the Ukrainian army as a special forces unit just a couple of weeks earlier. Formed during the Maidan revolution, in which they played a prominent role fighting the police and unseating Ukraine’s then pro-Russian government, Right Sector has since played a starring role in Russian propaganda as evidence of Ukraine’s takeover by Right-wing radicals.

It’s nonsense, Volodymyr Demchenko told me, back at their rear base in central Ukraine. Known as “Fransuz” or “Frenchman” (because his great-grandfather served in the French army after World War One), Demchenko is a 33-year-old documentary filmmaker from Kyiv with a hipster haircut and an engaging manner, who’s also become something of a Twitter celebrity since detaining the journalist John Sweeney for breaking curfew in Kyiv earlier in the war.

“Right Sector is a Christian, conservative organisation. Okay? Done,” he told me in his office cluttered with piles of books — Aristotle, Kafka, Umberto Eco — a postcard of Ernst Jünger propped on his bookcase next to the cafetiere and scent diffuser. “Like, I’m a liberal. I support LGBT, I have, like, all the time conversations about that here with the guys, and you know what, here I have freedom of speech to say that.”

Fransuz insisted that far-Right political movements were stronger in Western Europe than in Ukraine, citing the strong showing of those parties in the West compared to their marginality here. Yet Western journalists fixate on the far-Right symbols occasionally worn by Right Sector fighters, he told me with a weary sigh, “but I don’t think it’s a very interesting story, to be honest. They just want to be badass, it’s fucking cosplay, man. But if you’re talking person to person and try to find this ideology in him you wouldn’t. But here we don’t tell you what you can wear or what you can’t wear, because it’s bad for morale, every man can explain these things for himself.”

Formed as a coalition of Right-wing organisations during the Maidan Revolution, Right Sector suffered from an internal split when Andriy Biletskiy broke away to found the more radical Azov movement in spring 2014, which has since surpassed Right Sector in numbers and media attention — both good and bad. Part of the rift between them was Right Sector’s clampdown on far-Right symbolism, an aesthetic Azov leant heavily into until its recent rebranding.

Neither fascist nor National Socialist, despite the lurid reputation it has been given in Russian media, Right Sector instead draws a line of descent from both Ukraine’s early 20th century OUN nationalist movement for independence from the Soviet Union (whose red and black flag, for the rich Ukrainian soil and the blood shed for it, it has adopted) and from the anarchic, freewheeling Cossack war bands of Early Modern Ukraine. At times, the government has found the group a little too anarchic for comfort: in 2015, Ukraine’s previous president Petro Poroshenko futilely ordered them to disarm after a shootout with police in the western city of Mukachevo.

While foreign journalistic depictions of the group tend to flicker inconsistently between “Right-wing” and “far-Right,” Right Sector has always rejected the latter label, while Ukrainian academic specialists on Right-wing politics have stressed that the group’s electoral programme “does not contain any specifically ultra-Right or ultra-nationalistic ideas” and instead “seems to reflect a rather liberal worldview”. The group’s mission statement on its website asserts that its goal is “Ukraine’s liberation from both external — Kremlin’s — and internal occupation of clan-oligarchic groups, as well as struggle against the imposition of extreme-liberal, cultural-Marxist ideas upon the Ukrainian society.”

In a recent statement aimed at an English-language audience, the party’s leader Andriy Tarasenko insisted that Right Sector “is a nationalist formation; we unequivocally stand against all the fascist or Nazi things that Putin attributes to us. This is purely Russian propaganda, and we have nothing to do with such ideological positions.” Characteristically, the statement also notes that “We consider president Putin a liar and in general our people call him a ‘dickhead.’”

Three months and much fighting into his DUK career, Fransuz was a constant presence in the group’s rear base. One day I saw him staggering along beneath boxes of Elon Musk’s Starlink satellite internet receivers, which have won great publicity for their use by Ukrainian forces. These must be useful at the front, I suggested. He looked at me like I was an idiot. “This? No way man, if we took them to the front, as soon as we turned them on the Russians would send a missile right on top of us, as soon as they see all this data going up into the sky.” He shook his head and carried on with his endless bustling around.

Fransuz joined DUK at the beginning of the war, taking part in the defence of Kyiv, and then the heavy fighting in Barvinkove, where they destroyed dozens of Russian tanks in close fighting, and lost their battalion commander and 13 men to Russian shelling. In Barvinkove alone, they destroyed 64 Russian armoured vehicles in their two-month deployment. “We had a position on the road and they kept sending tanks, and we kept destroying them, every day — it was like a cemetery for tanks”, laughed Hasid, the group’s officer in charge of reconnaissance (he comes from the town of Uman, a pilgrimage site for Hasidic Jews, hence the name). “We saw one column, 600 vehicles. We let them keep coming, then we hit them from the front and kept hitting them from all directions and then we escaped in this car, driving over fields,” he said, pointing at a battered Skoda Octavia.

“Soviet tactics are just to use mass, lots of tanks and lots of artillery, infantry aren’t important in their doctrine,” Hasid added. “We instructed our new volunteers to use small groups in cars that are very mobile and can ambush huge columns — this technique will be in the handbooks now, I’m sure.” Have the Russians learned from their earlier mistakes? “No, No, No,” he replied. “Fear and panic. Even if the soldiers learned, their commanders still give them the same orders — and if they disobey, they shoot them.”

But in the Donbas, the Russians do seem to have learned from their mistakes: massing their troops together behind a devastating wall of artillery fire, the invaders are creeping forward every day, taking ground and eroding the Ukrainian army’s ability to fight. With the Ukrainians suffering up to 200 soldiers killed and 500 wounded each day, according to President Zelenskiyy, the next few weeks in the Donbas may decide the outcome of an increasingly brutal war.

“I was on the frontline from 2014, but now the situation is really crazy, fuck, lots of planes, artillery, everything,” “Veloshka”, the commander of DUK’s medical unit and wife of Right Sector’s leader Andriy Tarasenko, told me. A big woman with bleached blond hair and sleeve tattoos, Veloshka smokes and swears incessantly. “When you’re killed,” she told me, “I’ll be really upset, fuck, it will be an international scandal. Fuck, maybe I should just give you a puppy and send you away home,” she added, nodding at the litter of sleeping puppies on a nearby bed.

DUK’s two ambulances, named Hope and Pikachu, veterans of the Maidan revolution, are now serving with their crews on the Donbas frontline, painted dark green and hidden under trees in a secret location near Bakhmut. Soon I would join them, to meet and live with the DUK fighters on the frontline. Scrolling through Twitter in the meantime, watching Russian drone videos of Ukrainian positions being obliterated by accurate artillery fire, was not a reassuring experience.

The DUK battalion has deployed a company-sized formation to the Bakhmut frontline, divided into an HQ element and a number of small sections living in deserted cottages among the local Russian-speaking population. I was sent to live with 1 Section, a squad of artisanal craftsmen, farmers, writers and eccentrics, most from the West-Central Ukrainian city of Vinnytsia, who had joined up together at the start of the war. On my arrival in the courtyard of their cottage, I was seated down at their table under the trees and given a bowl of meaty borsch, by Kuts, a lean, heavily tattooed 48-year-old with a Cossack chub haircut and long drooping moustaches.

Kuts — the name refers to a type of benign devil in Ukrainian folk belief — is a jeweller and traditional swordsmith from Kharkiv. He showed me a medieval longsword on his Facebook page he was in the process of completing when the war began: “I didn’t get to finish it because of the katsabs (butchers),” he told me. Pulling out his self-forged, oak-handled combat knife from his assault vest, Kuts told me that the oak is a tree of great significance in Ukrainian folk culture, and that he saw his service in DUK as following the traditions of his ancestors. “Right Sector is like a modern Cossack Sich,” he told me. “Different people have gathered together from all walks of life in a time of need. We don’t care about gender, preferences, age. We learn a lot about our traditions, our ancestors, our family values, in order to not lose our connection to our Ukrainian culture, because those traditions are what make us Ukrainians. And now we have to fight for them.”

What is their political orientation, then, I asked? “Cossack Sich,” replied Kuts. “It’s a movement that doesn’t tolerate any political oligarchies, it stands only for the interests of the nation,” added “Bayonet,” a shy, humorous middle-aged man with a long reddish beard. “We are the Cossacks who will give our lives for Ukraine, without question, or we’ll take the enemy’s life. The Russians have a 10 to 1 advantage in this offensive, but every one of us can take out 100 Russians.” And what if Russia wins the war? “Impossible! No, No, Never!” replied Kuts in English, “Our motto is Ukraine or death, so they would have to kill us all.”

“The Russians will never be able to win a war here without using mercenaries,” he added. “They want to eradicate us because they fear us. Ukraine was always the best nation at fighting, and now we have confirmed that we Ukrainians are warriors at heart, and not any of this other bullshit.” Will postwar Ukraine be different, I asked. “Yes!” said Kuts, “We must kill the internal enemies, the fucking separatists. We are not the ones that just talk, and sit at home, the ones that have a ‘practical solution.’ We always look our enemy straight in the eyes, even the dead ones.”

Like other nationalist battalions, Right Sector’s deployment in the long-running Donbas conflict has long been controversial: they were accused of human rights abuses against suspected separatists by Amnesty International in the war’s 2014 opening months, a period characterised by the kind of intimate brutalities typifying civil wars. It is difficult to gauge how they are viewed by locals in the Donbas. “When I heard Right Sector were going to liberate my village, I was like ‘Uh, we’re all going to die,” one former Donbas resident, Sasha, told me, laughing at the memory: now she fights as a member of the group.

But for now, the Ukrainian government has embraced Right Sector. Previously used as a deniable proxy to seize strategically important positions from the separatist forces during the long years of frozen conflict in the Donbas, it has been formally incorporated in the Ukrainian army as a special forces unit, tasked with harassing the advancing Russians. It’s a mixed relationship, DUK fighters told me, in which the disadvantage of increased bureaucracy is outweighed by the sudden flow of new weapons donated by Western countries. I sat at the table one day as the group prepared a shopping list of new equipment — sniper scopes, night vision goggles, thermal weapons sights — to obtain from the government following a request from Pedro.

“It’s OK now we’re in the army,” 22-year-old Anna, or “Athena” told me in flawless English, with a remarkably posh accent acquired from watching Dr Who and Torchwood. “It’s a way of getting our weapons and doing our job more effectively, so it’s worth the extra regulations. The regular infantry have in some ways a more difficult job. We go on special missions and the rest of the time are just chilling, but they spend all their time in foxholes under constant shelling. It’s a very difficult job.”

The group is recruiting heavily, with its rear base in Central Ukraine crammed with new recruits training for combat beneath the tall trees, and learning how to use the new heavy machine guns donated by the West. Most seem apolitical: when asked why he joined DUK, one recruit, the local sales manager for a large German company, told me it was simply because he didn’t want his wife to be raped and murdered by Russian soldiers, “like in Bucha”.

Most have joined DUK for the chance to see combat as soon as possible, without the petty regulations of regular army life. Unlike the regular army, DUK has an anarchic, democratic atmosphere in which soldiers discuss orders with their commanders and feel free to add their own suggestions. “No-one here asks if you’re a nationalist, or an anarchist,” Athena told me. Like Fransuz and most DUK fighters I spoke to, she’s not a member of the Right Sector party. “We’re all just here to do our job.”

Brought up in a Russian-speaking Catholic family in Vinnytsia, the daughter of a surgeon, Athena was a poet and English translator before the war, with a sideline writing essays for American college students. She first volunteered for frontline service at age 18, straight from university. With her black hair cut in a neat bob, she was a distinctive presence whenever she returned from special missions in her baggy, second-hand British uniform, shrugging off her heavy body armour and ammunition pouches, and leaning her heavily-customised assault rifle against the table as she lit up a cigarette.

“I’m not a feminist,” she told me. “I don’t like modern feminism, they march around but don’t have solutions for anything.” A child prodigy, she was a contestant on the Russian version of Britain’s Brainiest Kid aged 11, and recently published a letter to the host, a Putin supporter, condemning the Russian invasion. In a perfect illustration of the complexities of the Ukraine war, Athena’s Russian husband, a dissident from Siberia, is fighting in an elite Ukrainian unit in nearly-surrounded Severodonetsk, and her uncle is a senior officer in the Russian army.

“Me and my husband would quarrel with these sweet little grannies who’d call us butchers and fascists at Victory Day parades in Kyiv, when they’d be shouting ‘Donbas, we are with you!’” she told me. “And we were war veterans — I remember one little granny calling us butchers and baby killers,” she tutted, dragging on her cigarette.

But the current war in the Donbas is not going well for Ukraine. Concentrating its resources in one front, the Russian army is now driving through Ukrainian lines like a slow, unstoppable bulldozer. In his secret cottage headquarters elsewhere in the village, I met the company commander “Tuman” (“Fog”), a map of the ever-encircling frontline spread out across the coffee table in front of him. A 29-year-old veteran of the French Foreign Legion, who had fought in Mali, Tuman had flown back to Ukraine from his job selling cars in Provence just before the war broke out, leaving his eight-month pregnant wife at home.

“It’s like the first part of World War I here,” he told me, “when massive artillery started to appear but there were still no trenches. During my service abroad in the Legion I’ve never seen such intensity of fire. But taking into account the intensity of fighting we cannot just wait around. We are taking part here in active defence, we are doing counter-artillery and counter-sabotage work. All we can do is slow down the Russian advance.”

The disparity of materiel between the opposing forces was total, Tuman told me. “Russia uses almost all the resources they have, strategic aviation and submarines. It’s a force created for a war against Nato and now they use it all against us.” But he had no option but to fight, Tuman told me. A member of Right Sector since the very beginning, in the Maidan revolution, he told me: “I fight for freedom. My country is just a bit older than I am, but Ukraine is ready and I’m ready. Now we have the majesty of fighting, even though it sounds pathetic. We are not helpless. We can fight!”

Tuman’s deputy in holding back the Russian onslaught is his platoon commander Pedro, a giant of a man, covered in tattoos of ancient Ukrainian warriors and kings, the solar wheel of Slavic paganism on his chest, and a rosary around his neck — he’s a practicing Catholic from the Western city of Ivano-Frankivsk. Fighting alongside his younger brother “Bob”, Pedro plans and leads the missions into no-man’s land to take some of the pressure off the regular troops struggling to hold the line.

I joined Pedro’s mortar team on another mission, jostled in the back of his SUV as the fighters in the front nodded along to heavy metal on Ukraine army radio, swerving at top speed to avoid the pheasants scuttling along the country lanes, the driver scrolling through his mobile phone for the latest checkpoint password. The Russians had spotted the mortar position, I was told, and now was the last chance to hit them from the location before it was abandoned. Hidden in the undergrowth, the mortar squad had laid out a dozen heavy mortar rounds ready to be fired: “Admin”, a young Tatar Muslim from Russian-annexed Crimea, and a chef before the war, showed me where he had scrawled “Crimea is Ukraine” on them in marker pen.

As the sun began to dip over the steppe, the squad fired the heavy rounds at the Russians in quick succession, as other fighters pointed at the sound of munitions buzzing dully through the air around us. “Is that ours?” one asked, to a shrug. The layout was confusing: the Russians were more or less everywhere around. The Russian return fire landed harmlessly in the fields a few hundred metres away, a couple of mortar shells exploding in scattershot puffs of grey dust. My driver, “Kolos”, pointed at the thick plumes of black smoke now rising from the white building on the edge of Svitlodarsk where the Russian target was based. “Good work,” he said.

But for DUK’s fighters, their mission in the Donbas is frustrating. Their semi-guerrilla war of harassing Russian troops is necessary, but not what they came here for: they want to be assaulting the Russians head on. Unlike the infantry forces holding the trench positions on the first lines, they are based in a location where they can reach any sector of the Bakhmut front within a short drive, but which is itself strangely free of Russian artillery fire.

Driving around Bakhmut’s outskirts, you see the forested hillsides wreathed in smoke, and the flashes of cluster munitions as the Russians rain death on the Ukrainian defenders. But DUK have been deployed in what they see as a frustratingly boring island of rural peace at the heart of the largest war in Europe since 1945. The roar of outgoing Ukrainian artillery is constant, and the sound of incoming Russian artillery, the different rocket launcher types discernable from the pitter-patter tempo of their munitions, punctuates the day as it falls on nearby Ukrainian lines. But only once, when an incoming Russian missile made the windows quake, and sent me out for an unnerved 3am cigarette under the stars with the sentries, did Russian artillery feel like more than an offstage menace. “It’s no good just sitting on your ass,” Petrik complained to me, “I need to work.”

But apart from their combat missions, the squad lived lives of quiet rural domesticity, cooking, cleaning and smoking endless cigarettes, watching the Netflix show Euphoria on their phones, and enjoying the cool breeze in the trees. For Ukraine’s industrial heartland, the Donbas is strangely bucolic. Sitting under the cherry trees, the long days spent with them were like something from a Russian novel: one day we went to the village banya together, where a crop-headed boy shoved chopped wood into the furnace as we sweated ourselves clean in the steam (“Now you are one of us,” Athena told me afterwards). They bought jugs of raw milk from local farmers, and accepted big enamel bowls of cherries from the villagers, brought as gifts. “You know what they say,” Athena told me, “our soil is so fertile because of the dead bodies of our enemies.” One day, I went mushroom-picking in a nearby forest with the medical unit, as bursts of machine gun fire echoed dimly through the trees from somewhere nearby. “Thor,” a chubby, kindly paramedic pointed angrily at a pile of trash local picnickers had left under a tree: “Fucking human pigs,” he said.

With a tattoo of a Carpathian mountain scene on one arm, and the portrait of Ukraine’s national poet Taras Shevchenko on the other, Thor had joined up with his pink-haired wife “Iren” who he was serving alongside in the medical unit: “I would feel sad if we were apart,” he told me. For Thor, love of Ukraine was not just for the abstractions of flags and borders, but for its mountains and forests, lush meadows and broad flowing rivers. He told me that he had joined Right Sector at the beginning of the war because he liked its ideology, and because of its reputation from Maidan: “My mama likes Right Sector,” he smiled. What was its ideology, I asked? “Killing Russian bitches!” interrupted “Lektor,” a 19-year-old medical student from Lviv. Thor waved him away smiling. “It is following the example of our ancestors, our grandfathers who created this country, for the independence of our nation, for living by our own rules. We don’t need foreign things from anyone, and we won’t take what is not ours from anyone. This is our war of independence.”

If there’s one thing that bothers DUK’s fighters most of all, it’s Right Sector’s reputation in Russian media — and often in the West — as extreme Right-wing radicals. Tuman was furious the day I arrived because a French journalist who had visited them at their rear base for a day described them as neo-Nazis, an epithet based on the self-consciously edgy frontline aesthetic of a minority of their fighters rather than their words or deeds. “Just write what you see,” he replied, when I asked him how he would describe their ideology, “We want truth, just as it is. We can allow ourselves the truth.” Some of their tattoos give off a fearsome appearance, though one belied by the gentleness and hospitality of the soldiers themselves The rare Nazi-adjacent markings were written off as legacies of youthful dalliances with more hardline groups; pressed on their beliefs, all the fighters disavowed any extreme sentiment:

“We’re not fascists, you might sometimes see people wearing these symbols but it’s not serious, we do it to troll the Russians because they call us Nazis,” Athena insisted. “We understand in reality that the Nazis were as bad for Ukraine as the Communists were. Me and my husband have got anarchist friends, fascist friends, nationalist friends, lesbian friends — that’s just how it is here in Ukraine. Before you go to war, you’re into Right-wing politics, political violence and stuff, and then when you come back having seen it, you just want to drink cocktails in Kyiv and spend time with your family, enjoying life.”

“A lot of notions about Right Sector come from liberal left propaganda, but in reality we are just ordinary Ukrainians defending our country, our sovereignty, and our Christian values,” Lis or “Fox,” the section commander, a taciturn blond-bearded 27-year-old solicitor from Vinnytsia told me. A fan of death metal, Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series, and the Warhammer 40k gaming universe, Lis is the local head of Right Sector in Vinnytsia. “2014 was a hybrid war, and this is a Great War,” he told me. “But it doesn’t matter which war, the Russians will die either way. You have to believe in the [40k] God-Emperor,” he grinned.

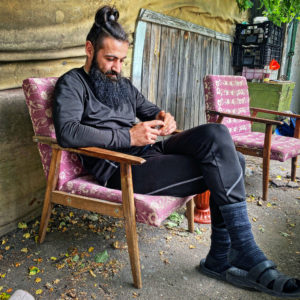

Lis joined DUK along with Athena, Petrik and “Boroda” or “Beard,” a dark-complexioned hipster with a top knot hair style and long black beard. A beekeeper and mead brewer, Boroda missed his hives. “It’s very relaxing working with the bees. When I’m with them I forget about everything else. When I lived in an apartment in Vinnytsia, I kept them on my balcony,” he smiled shyly.

“We call him “Moldova” because perhaps he is a gypsy,” laughed Athena, “but he’s a good gypsy.” “I’m a quarter gypsy,” Boroda replied. “All gypsies are cockroaches,” replied Kuts, spitting on the floor, as they all laughed, Boroda included. Like all soldiers, especially in elite units, the squad roasted each other mercilessly. The highlight of each evening was Petrik’s phone calls to a drunkard wannabe recruit, entirely unfit for service, in which he pretended to be a strict colonel imparting life advice as they all clustered around the blue glow of his mobile phone stifling their laughter. They’d play fight constantly, fencing with metal pipes, each taking turns to cook and clean, and talking about the first drink they’d have when they got home: alcohol is strictly forbidden on the front line, its place filled by luridly colored energy drinks. Petrik, who had just bought a 32-acre farm, was angry at the Russians for — along with everything else — preventing him from sowing his first cabbage crop.

Athena, too, is resigned to the conflict between her desire to fight and her dream of an ordinary middle-class European life. “Ukraine has always been a country at war. It’s just geographical determinism, I guess,” she told me. “It was weird going back to Kyiv the first time after the frontline, but I guess that’s what we’re fighting for. I want people to drink iced lattes, smoke weed, make love. After the war I want to live my best life, because I had lots of friends who can’t do that any more.”

But instead of living their best lives at home, they are billeted in the far east of Ukraine in a war now turning in Russia’s favour, among a local Russian-speaking population with whom relations are at times strained, many of whom would prefer to live under Russian rule. While some local farmers smile and wave, and bring gifts of food, others are distinctly unfriendly. “Some are friendly, some not, some are enemy. You won’t know until they kill you,” cautioned “Paul”, a softly-spoken middle-aged tour guide from Kyiv turned paramedic.

Walking through the long grass and undergrowth of the semi-abandoned village to the local shops with the heavily armed soldiers, to buy energy drinks and ice creams from a pointedly unfriendly shopkeeper, Athena highlighted the eerie atmosphere of dereliction. “It’s weird out here, it’s almost as bad as Detroit,” she said with wonder — Athena had spent a year in a Michigan high school as an exchange student. All from elsewhere in Ukraine, they were fighting among a local population whose loyalty to the nation was not guaranteed, and found it a strange and frustrating experience.

“In the majority of countries, there’s one national language, but the problem here is that people refuse to use the national language,” Kuts said. Kuts had grown up in a Russian-speaking family in the border city of Kharkiv, he told me, but now he disavowed the language in search of his Cossack roots. He had been a Young Pioneer under Communism, he told me in broken English: “Shit. Fuck Communism, Fuck Lenin.” “Hora”, a young commercial filmmaker, added that because he was from Western Ukraine, he had never been bothered by the language question, but seeing people here refusing to speak Ukrainian distressed him.

“I want to make a big explosion in Moscow,” Bayonet, who had lived a few years working in Balham, suddenly announced in English. “Voronezh, Rostov and the Kuban [in southern Russia] are Ukrainian lands,” he continued. “We stand for historical justice, and we have to return these lands to the nation.” But Ukrainian forces are struggling simply to maintain their foothold in the Donbas. If and when the Right Sector fighters get their wish and tackle the Russians head on, many, perhaps most of them will die over the course of the summer. “We know that if the Russians capture us, as Right Sector, they will kill us straight away, on the spot,” Athena told me. “And for me, as a woman, well… you understand what would happen. That’s why we each carry a grenade with us.”

Returning to Dnipro, a haven of charming cafes and hipster cocktail bars a five-hour drive west from the front, the hotel bellboy who guided me through the blacked-out corridors to my room had a Right Sector screensaver on his phone; he beamed with pride when told we had just spent time with them. Catching up with a liberal Ukrainian friend, I told her I had just been at the front with Right Sector: “Yeeees!” she replied, “They are super cool!”

“Compared to other nationalist movements,” Lis told me, “Right Sector didn’t mess up like the others. Right Sector is the best nationalist movement in Ukraine.” But while vital in war, they know they are a marginal presence in peace. “The government will try to eradicate us after the war,” Petrik warned, “because they are afraid of us, because we stand for the truth. The politicians are afraid of revenge.” Tuman, too, sees the war as a watershed moment for Ukraine and for Right Sector, the greatest clarifying moment since independence in 1991. “This is like our postponed war for independence,” he told me. “Maybe we could have had war in 1991 and a peaceful 2022. But Ukraine didn’t introduce fierce wartime laws. The economy wasn’t transformed. After this war everything must change.”

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com