The Christmas lights switch-on in my town last weekend was epic. Streets were blocked off, the market square was filled with funfair rides, and stalls selling hog roast and hot-dogs, glowsticks, candyfloss and wreaths.

The countdown was MC’d by a man in a huge top hat and Santa. The lights went on, everyone cheered, and the season of tinsel, gluttony and shopping was declared opened. Looking around the packed square, I marvelled at how many of its details seemed both ancient and modern: at once a millennia-old winter feast, and also a celebration of manufacturing, power generation, and material abundance.

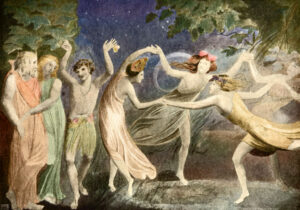

But if, the following morning, my local church celebrated the older version of that festival, by lighting a candle on the Advent wreath, the European tradition of winter excess is older even than Christianity. The Romans celebrated Saturnalia in December, and then the feast of Sol Invictus on the winter solstice. December 25 was also the birthday of Mithras, god of light and loyalty. Beyond the reach of Rome, Germanic and Celtic societies celebrated Yule, also linked to the solstice, by bringing evergreen foliage into homes and sacrificing to Odin’s Wild Hunt.

When Christmas Day was officially designated under Constantine in 336AD, it absorbed many pre-Christian traditions, including evergreen decorations, the Yule log along with the light and feasting. This all makes sense: the weather is miserable at this time of year, it gets dark at 4pm, and everyone needs a pick-me-up. So, in much the same spirit, my Saturday evening the market square also contained the ancient keynotes for a winter warmer: light, calories, and the local community. Despite the near-total absence of Christian religious elements, the Saturday evening in my market square did contain a winter godling, of sorts: Santa Claus.

His origins lie with St Nicholas, whose day is celebrated today. Said to have been a Turkish monk, he lived around a century before Constantine gave us Christmas Day and was renowned for his generosity. By the Renaissance, he was the most popular saint in Europe: the patron of Russia and Greece. And though the veneration of saints largely vanished from Protestant countries after the Reformation, St Nicholas survived.

In keeping with the syncretic quality of Europe’s winter festivals, too, St Nick retained a pagan edge: a sidekick called the Krampus, a brown, horned monster who brandishes a birch whip and threatens misbehaving children during the Advent season. On Krampusnacht, or Krampus Eve, the creature frightens children into good behaviour and cities across central Europe still host a “Krampuslauf” the evening before St Nicholas’ Day: a parade in which participants dress as horned demons, and try to scare the crowd.

St Nicholas travelled to New York as “Sinterklaas”, with Dutch migrants in the 17th and 18th centuries. There, fittingly for the new world, he made a fresh start. He was soon on his way to the cheery modern persona first crystallised in the 1822 poem, The Night Before Christmas, in which now-canonical features of Santa first came together: the flying sleigh, the jolliness, the reindeer names, and the sack of toys. His reboot included leaving the Krampus behind, in the Old World’s cultural hinterland. That entity’s menacing, disciplinary role survives for American Santa only in vestigial form, as the “naughty or nice” list.

The year before Clement C. Moore wrote The Night Before Christmas for his six children, Michael Faraday invented the electric motor, setting (literally) in motion much of the world we know today. Just few years later, Samuel Morse invented the telegraph. In other words: American Santa arrived concurrently with, and inextricably from, what Marshall McLuhan dubbed the Electric Age. Electric Santa also coincided with an American 19th century of breakneck industrialisation: an age of innovation and infrastructure-building, real-terms wage growth of 40%, new material abundance, and also the emergence of vast inequality: grinding poverty for many, against the Olympian wealth of the Gilded Age “robber barons”.

But it was the 20th century that was, par excellence, the age of Electric Santa: the now-familiar icon of cost-free consumer abundance, underwritten by flourishing (and usually, implicitly, American) industry. Even his red-and-white livery is, famously, a byproduct of that industrial powerhouse’s pervasive cultural reach and economic dominance: the result of a 1931 branding exercise by Coca-Cola. This version of Santa has reigned for my lifetime to date, as dominant godling for winter celebrations, whether in America, Europe, or even further afield.

A benevolent patriarch, the mythic Electric Santa heads a workshop full of industrious elves, who toil away all year to make each child the material goods he or she most desires. These magical products are then delivered frictionlessly, at no cost, as a blessing of the festive season. It’s hard to think of a more perfect godling for the idealised era of industrial abundance and rising living standards — not to mention McLuhan’s Electric Age collapse of physical distance. How else is Santa to get all round the whole world in one night?

But as we exit the industrial age for a digital future, there are signs that the runners may be coming off Santa’s sleigh. Today, Electric Santa exists in the real world, at the head of a team of largely-invisible elves who frictionlessly delivers to us anything we could possibly ask for. Except his name is Jeff Bezos, and the reality is less apple-cheeked old man with ruddy-faced elves spreading cheer, than factory slavery, monopolistic price-gouging, and warehouse workers peeing in bottles to avoid incensing the algorithm.

Under these conditions, perhaps it’s no surprise to find more sinister festive icons coming to life. But now the disciplinary role isn’t taken by the horned Krampus demon, but by an altogether more modern, smiling figure: the Elf on the Shelf. These effigies, which spawn a Mumsnet hate thread every Christmas, come with a story about how elves visit children in December, then report back to Santa on who has been naughty or nice. Behind this lurks an edge of what the novelist Ewan Morrison calls “cute authoritarianism”: the technocratic surveillance tyranny that governs an Amazon warehouse, but softened with a layer of cuddliness.

If the Elf isn’t literal enough, parents can take a still more direct inspiration from Santa Bezos, and install an Elf Cam in their kids’ bedroom. Forget being terrified into good behaviour by Krampusnacht: today Santa’s disciplinary other compels obedience by training kids to internalise a sense of being continually watched.

McLuhan saw this coming, too. For him the Electric Age was less about the spread of light, than the collapse of distance into one planetary “global village”. This term has been widely adopted by activists as a positive development, signalling worldwide solidarity. But contra the utopians, McLuhan’s vision was much more ambivalent. For him, mass communications turning the whole planet into a single community was less about retrieving the medieval village as a positive emblem of community, than of suffocating transparency: 360-degree surveillance, petty gossip, and endless power-games.

McLuhan died in 1980, before mass adoption of the technology that would realise his predicted “global village”: the internet. But today we live in a world of all-ways surveillance, public moral shaming, and “nudge” governance, whose ideal emblem is less Electric Santa than the cute-authoritarian Elf on the Shelf. Meanwhile, jolly abundance has become, in the digital age, post-industrial anomie papered over by planetary labour arbitrage and global supply chains. Under this new order, presided over by Santa Bezos, purchasers of Christmas cards may find the pack contains a desperate plea from the “elves”: in reality, slave labourers in a Chinese prison.

So perhaps it’s not so strange to find Santa evolving again. Electric Santa absorbed the Krampus, reducing his menacing disciplinary role to a blacklist – but more recently, McLuhan’s “global village” has allowed symbols to travel frictionlessly. And one consequence has been that the Krampus has belatedly followed Sinterklaas across the Atlantic, after Krampus images began circulating on the internet in the 2000s, inspiring Krampus parades in numerous American cities. This time, though, the tables are turned. Instead of becoming a vestigial trace of Santa, this time Santa is a vestigial trace of the Krampus, who has evolved into what the Washington Post recently called “a demonic anti-Santa”.

Even as the post-industrial West grapples with stagnation, polycrisis, and the looming spectre of climate change, global supply chains have made Santa’s workshop a reality – after a fashion. But it’s already clear this comes with costs, as well as a side-order of digital authoritarianism. Against this, does it still make sense to venerate a winter godling whose key role is manufacturing and distributing consumer goods? Perhaps not.

But that’s no reason to abandon winter feasting. The weather is still cold and wet, and it still gets dark at 4pm. The Christian associations may be fading, but the ancient need for a winter feast is as strong as ever. And festivals mean godlings. So while it’s perhaps no wonder the previously jolly electric Santa is taking on darker colouring, maybe this is for the best. I’d rather have the Krampus than a Santa Bezos elf-cam.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/