In 1958, the French philosopher Guy Debord organised a “raid” on a Belgian conference of art critics. His group, The Situationist International, phoned attendees and read out their manifesto. They scattered it in the street. They posted it to the press. The document denounced the event as little more than “confused and empty chatter about a decomposed culture”. The conventional critics’ days were over, they warned the assembled delegates: “We will reduce you to starvation.”

Did they triumph? Certainly, such politicised “raids” on cherished artistic artefacts and spaces seem evermore common today, from statue topplings to Old Masters splattered with soup. Last weekend was no exception: at Trinity College, Cambridge, an activist protesting the Israel-Palestine conflict destroyed a 1914 Philip de Laszlo oil painting of Lord Balfour using red spray paint and a box cutter.

Much has been written about how this represents an attack on the West’s values and legacy. But surely, if this were what we believed, the response to this vandalism would be swift and punitive. And yet no such response was forthcoming: Trinity College managed little more than a limp expression of “regret” and an offer of counselling to anyone affected. At the time of writing, no arrests have been made. A cloud of official forgetting seems already to have settled over the event.

This is less bewildering, though, when you understand the “intervention” by Palestine Action not as an attack on our artistic heritage, but as a profoundly conservative expression of that heritage: in particular, of the modern legacy of permanent revolution, inaugurated by 20th-century radicals such as the Situationists.

For this group, the 1958 art critics’ conference was just one more deplorable iteration of the “society of the spectacle”, a pervasive form of capitalist tyranny propagated by mass media and consumerism. Here, image-making takes precedence over material reality, while obedience is ensured by dissolving organic social relations. Needs are replaced with commodified desires, consumers become purely passive, and capitalism becomes inescapable.

The Situationists set out to break down this regime by challenging “the spectacle of a false encounter”. They developed disruptive forms of performance, participation and collective authorship. Cultivating randomness, they sought everywhere to re-invigorate the masses by disturbing the manufactured consumer spectacle.

Did it work? Well, yes and no. The Situationists were certainly influential. And their legacy has spread well beyond the art world: the climate activist group Extinction Rebellion, for example, were explicitly inspired by the Situationist International. Was it radical, though? Again, yes and no.

In one 1966 manifesto, the Situationists decried “the bygone excellence of bourgeois culture” — a legacy they believed had already given way to ugly managerialism governed by “the rhythm of the production line”. In this context, “the university is becoming”, they argued, “the honest broker of technocracy and its spectacle”. Within this flattened, hollowed-out infrastructure, the Situationists argued that “the banality of everyday life is not incidental, but the central mechanism and product of modern capitalism”. And, they argued, to resist it “nothing less is needed than all-out revolution”.

This would, they imagined, free the entire accumulated legacy of the now-defunct bourgeois order for revolutionary purposes, enabling radicals to “destroy the spectacle itself, the whole apparatus of commodity society”. This “liberation of history” would spell the end of all repression, in favour of “revolutionary celebration” and “untrammelled desire”.

Or so they hoped. The manifesto heavily influenced the Paris ’68 riots: Situationist slogans were distributed by the “Occupation Committee of the People’s Free Sorbonne University”. Half a century on, though, re-reading the Situationists’ declarations evokes a sense of both admiration and tragedy. Admiration, for how prophetic they were; tragedy, for how partial their revolution turned out not to be.

Given now-common complaints about universities enabling the spread of technocratic managerialism, it’s hard not to see the Situationists’ critique as prescient. And in this context, taking a box-cutter to a 1914 oil painting might make sense — for the world that painting depicts has already been emptied of meaning, and there’s no legacy to protect.

Except there is: the legacy of the ‘68ers themselves. Today, just over half a century on from the riots, it’s the inheritors of the Situationists and ‘68ers that command the heights (such as they are) of contemporary culture. Radical critique is the default mode of the modern academy; you’ll struggle to get funding for research that doesn’t set out to problematise, deconstruct, decolonise, queer or otherwise liquidate the last moribund fragments of the bourgeois culture Debord was already pronouncing dead in 1966.

The art world, meanwhile, has comprehensively re-institutionalised the once-revolutionary style of Situationist intervention, via an often publicly-funded infrastructure whose default stance is also — within certain limits that artists violate at their peril — radical critique. And across academia, the arts and the rest of the progressive consensus, untrammelled desire is so unchallengeable a good that those trying to restrain their own masturbatory habits are traduced in the press as fascists. Meanwhile, respectable academia and publishing knocks ever louder on once-forbidden sexual doors, such as bestiality or paedophilia, while government-funded quangos dole out hundreds of thousands in grants for hardcore sex films masquerading as “art”.

In other words: everything the Situationists called for is now institutionalised. And the final tragic irony of this partial triumph is the way Situationist-style interventions, staged for the camera, critique “spectacle” through spectacle itself.

For Debord never anticipated the internet. His critique of “spectacle” targeted mid-century mass media: cinema, radio, and television. These forms had one thing in common: they were one-to-many. The effect of such image-making was to impose the synthetic, consumerist fantasy-world of the ‘spectacle’, in a tyrannically top-down way. In response to the autocratic stranglehold this exerted over the public imagination, the aim of Situationist praxis was to jolt the masses from mediated passivity into active, decentralised re-engagement with the world’s strangeness — and its revolutionary possibilities.

What happens, though, when the media is no longer one-to-many, as it was in the Sixties, but many-to-many, as is the case with social media? Back in the Noughties, when social media first exploded, the leftist arty circles I frequented at the time responded to this new decentralisation of image-making with a revived interest in Situationism. Creative collectives sprang up; performance art and street protest merged; it seemed for a moment that internet-enabled image-making and subversive organising might offer a way out of the deadening passivity of mass consumerism.

How naïve that all seems in hindsight. For these supposedly liberatory new forms were almost instantaneously colonised by the spectacle they sought to disrupt. The interval between the first spontaneous, playful flash mobs and the adoption of this format by marketers was vanishingly brief. And a decade or so on, such content is the bread-and-butter for a new, still more total, economy of spectacle — in which all of us, all the time, are called to be both content and consumer.

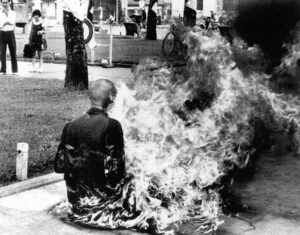

Clickbait creators skip from discourse to discourse, spreading discordant viral material; even brutality and horror have currency less for the reality they represent than as the spark for online discourse. Street fights; stabbings; cannibalism; servants falling out of windows: it’s all fodder for the dispassionate-seeming phone camera, and for those farming chaos for engagement. In this economy, too, street protests exist only to the extent they’re represented in the digital spectacle: every such gathering attracts the same complaints of mainstream press cover-up. Smaller-scale protests, meanwhile, increasingly explicitly orient themselves toward the virtual, prioritising not political change but pure virality, whether via soup-based interventions, vandalism, or bodily fluids.

To what extent does any of this transgress anything? Well, some kinds of subversive intervention in the image-making space still incur real-world punishment. Even a regime supposedly ordered to permanent revolution retains some taboos. But the list of genuinely forbidden opinions and acts doesn’t seem to include vandalising paintings of dead politicians. On the contrary: damaging a surviving fragment of bourgeois culture reads less as revolutionary today than as an act of slavish devotion to orthodoxy.

And the only way to make it even more completely orthodox is to stage it for the camera. Today the Situationists’ subversive energy has been re-absorbed by a new orthodoxy — one even more completely governed by commodified “spectacle” than that of Debord’s time.

No wonder, then, that the Trinity vandal is clearly a dutiful young consumer, transporting her vandalism kit in a Mulberry Cara backpack: a limited-edition designer accessory that retailed for £995 when released, and still sells for hundreds second-hand. In the new order she represents, vandalising the crumbling remains of bourgeois culture is less radical than routine: only a slightly more pronounced version of the “queering” and “decolonising” that every generation of progressives has been engaged in since ‘68. And the calculated staging of this act in turn signals the total recapture of Situationist disruption, as merely another form of digital spectacle.

The Trinity event reveals today’s crop of young pseudo-activists as they are: suffocatingly conservative, iPhone-wielding foot-soldiers for the reigning dogma of permanent revolution. Designer backpacks on their shoulders, they dance on the weed-choked tomb of a civilisation their grandparents destroyed: “confused and empty chatter about a decomposed culture” is all they have.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/