In 1792, the last Frenchman to be honoured with the title of dauphin was thrown in Paris’s Le Temple prison. The young Louis XVII was never freed; he died aged just 10.

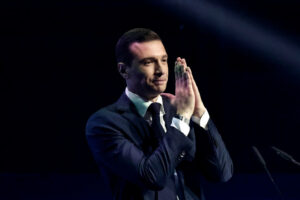

More than two centuries later, the nickname had devolved to remarkable commoner. All of 28, Jordan Bardella has no king. Instead, he has a queen, one who has been very good to him, raising him to the presidency of the Rassemblement National (RN) while she seeks that of France itself. Following last week’s European victory — in which RN won in every region in France — the queen and the dauphin now bestride the nation with as much confidence as their royal predecessors. Unlike their predecessors, however, they also command the present support of the people.

Still, Bardella and Marine Le Pen make for a very odd couple. France is used to her presidents being énarques, graduates of the Ecole National d’Administration and other elite academies. No woman has become President, and only two, Edith Cresson and until earlier this year, Elizabeth Borne, have served as prime minister. Neither did so with distinction, nor did they serve a good length of office to prove themselves.

Bardella, in contrast to all, was raised in rent-controlled housing in the Parisian suburb of Seine-Saint Denis, his parents of Italian and Algerian origin. He did well at school, but dropped out of a geography course at the University of Paris-Sorbonne to join the Front National, forerunner of the RN, at 16. He quickly became a departmental secretary, formed a group called Banlieues Patriotes (a challenge to the banlieues better known for their Islamist radicalism), and was taken into the party headquarters, where he was spokesman, deputy president and, in 2022, temporary then full president.

I’ve seen him perform before a RN crowd twice: once, in 2023, in a convention organised to reward the party’s local leaders in Le Havre; and once, in April, in a vast hall in France’s second city, Marseilles. In both, he gave elaborate genuflection — physically and verbally — to his patronne, who had “faith in him always”. And so she should, since his natural political talent and charm, with a small, slightly shy photogenic smile permanently on show, make him a huge asset.

A few months ago, Bardella was voted the most popular politician in France, which could irk a woman who has worked for decades, from notoriety to celebrity, to get where she and her party are now. But in both venues, they spoke one after the other, with every sign of affection and with great passion: she invoking the beauty of France’s countryside and settlements, as she likes to do; he ripping into Emmanuel Macron, whose presidency was going through a bad patch, with worse to come. In Marseilles, both took time to emphasise that, in government, they would not be bound by the rules of the European Union, unless these benefitted France.

If Macron’s gamble to call a snap election fails, and the RN wins, then the President is almost obliged to appoint Bardella as prime minister. The liberal-conservative Les Republicains have said they will join an alliance with the RN, a historic departure that Le Pen has since described as “brave”.

Yet were Bardella to enter the Matignon, the PM’s residence, he would be obliged to leave the much easier task of holding the present administration to ridicule, and instead face up to real politics in a large state where millions would still hate him on principle. His talent is now exercised in raucous opposition politics: then, it would be in endless complexities.

Is he cut out for the struggle? Pascal Humeau, a former communications expert with the RN, says of him that “his ease, his enthusiasm, that you can feel today, we had to work on it for months and months”, adding that even Bardella’s smile and greetings were products of painstaking training. He does appear to sincerely believe in Le Grand Remplacement — the name of a book by the writer Renaud Camus, who proposed that elites were secretly ensuring that floods of immigrants, cheaper to employ and grateful to those who allowed them to enter the country, as replacements for the indigenous people. Le Pen herself, when first encountering it, said she thought it absurd.

And in any case, it is Le Pen who will face the largest test: she will be RN’s candidate for the presidency scheduled for April 2027. Polls conducted earlier this year show her well ahead of the other challengers — with 36% of the vote; former Prime Minister Eduard Phillippe and Gabriel Attal, the present 36-year-old Prime Minister, both on 22%; and the left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon on 14%. Second-round polls are much closer: of her possible opponents, she would beat Mélenchon with ease, 64%-36%. But she would win over Attal (if he were the candidate) by only one point, and is on level pegging with Phillippe, a popular figure (though presently under investigation for possible corruption). Macron, his two-term mandate completed, could only look on.

These results, three years before she has to get real, still emphasise her largest challenge. She must not be seen to be too extreme; has she done enough to bury the Le Pen family curse of far-Right fanaticism? In a leaked private conversation from 2021, she had said that Eric Zemmour — the further right presidential contender with his Reconquête party — “makes me look reasonable. He is into the clash of civilisations, while I say yes, Islam is compatible with the Republic.”

At the same time, anxious not to be seen to be too mild, she has celebrated the expulsion of Mahjoub Mahjouni, a Tunisian Imam who preached in the town of Bagnols-sur-Ceze in the department of Gars and who specialised in calling the French tricolour “Satanic”. According to a report which the police had compiled, he had said that “we won’t have any more of these tricolour flags, which poison us, and give us headaches”: he thought it a pity that “mosques don’t produce fighters, as in the time of the prophet. women were inferior, feeble and venal, who must be guided and controlled by men, and hidden away in the name of religion”. On the daily message the RN puts out, usually featuring Bardella and Le Pen smiling broadly, waving joyously, she wrote that “the RN never allows our flag to be trampled into the earth of the French republic”.

Such constant, sharp-edged criticism, which Bardella and Le Pen both deploy in confronting the large Muslim community, has found favour — indeed, it has forced Macron to follow suit. Le Pen believes that many Muslims live decent lives and cause no trouble: she also believes a large proportion, especially of the young, do not. Gilles Kepel, France’s leading expert on Islam — and no fan of Le Pen — writes in his Terror in France that the tendency to label as “Islamophobia” all criticism of Muslims “makes it possible to rationalise a total rejection of France and a commitment to Jihad by making a connection between unemployment, discrimination and French republican values”. The many murders of French citizens by young Islamists have narrowed the space for toleration and exculpation: Le Pen, while careful to avoid extremes, is with Bardella at the head of this popular backlash.

But how long will that stay the case? The dauphin and his queen have already chosen their future titles: M Le Premier Ministre, and Mme la Presidente. He would be in a dauphin-like, subordinate position, as all French premiers are obliged to be: but should he succeed in that office, confounding his critics by showing a grasp of the hugely difficult role, he may himself progress to being a republican king.

Moreover, despite being on the back foot, Macron is still in charge of a timetable and still in the Élysée. If he wins in July, the Le Pen-Bardella charge will be halted. And with some support returned to him, Macron could rally for the last years of his reign, and use them to try to reduce the RN. Beneath the charm and the calm, Bardella must fear such failure. To which his Queen, in Lady Macbeth guise, will surely tell him to “screw his courage to the sticking place, and we’ll not fail”.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/