Can DOGE Handle the Bureaucratic Imperative?

by Thomas Buckley at Brownstone Institute

Bureaucracies are fascinating creatures – and, at all levels, government, corporate, academic, institutional, creatures they are.

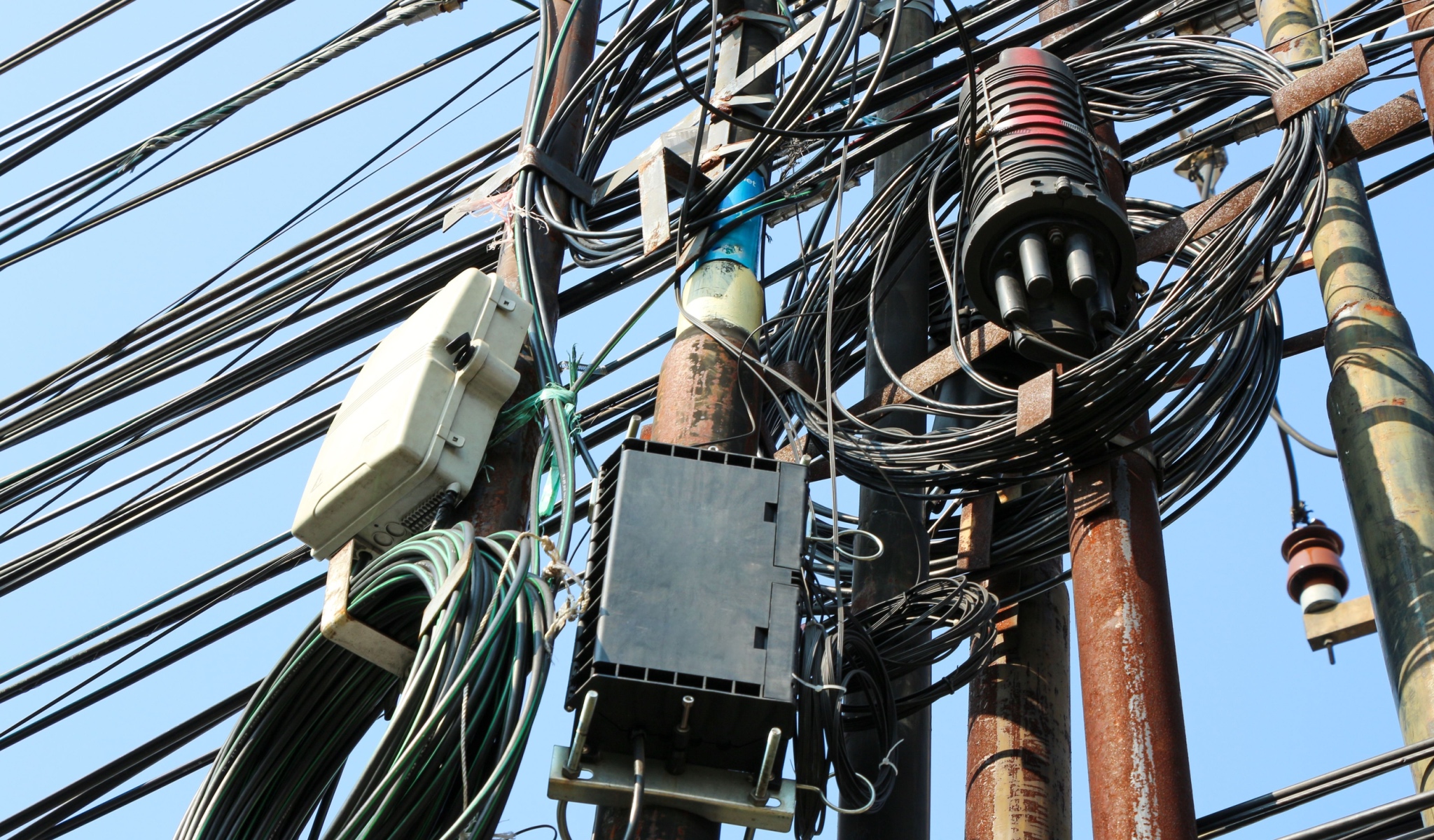

They are living things interconnected – either internally, when, for example, seven people have to sign off on a two-paragraph memo, or externally, when the creation of a new job and/or task in one bureaucracy necessitates the creation of another job in another bureaucracy simply to be in compliance and have the ability to communicate with the other organization.

It is depressingly true that a shockingly large percentage of government and educational and even private sector bureaucrats exist solely to talk to one another and add nothing to the overall goals of the organization.

And this should be the mindset – at least at the start – of the newly-created Department of Government Efficiency because even eliminating one person and/or program at the federal level will have a ripple effect throughout society.

When bureaucracies get more people, they do more stuff. When tasked with more stuff, they get more people and then the new people realize there are other things the new program could be doing so more people are brought on to handle tasks that were never previously imagined as even remotely necessary for anyone to undertake, let alone complete.

Thought experiment – if you want to move your friend’s couch, having three people is probably better than having two, even if one of them is only standing to the side and drinking a beer and saying “no, a little to the left and move it more upways” as you and the other guy struggle it down the stairs.

But what if bringing an extra person to help move the couch caused the couch to grow? What if recruiting five people to help move it made it five times as heavy or it became three couches?

What if the couch was able to fill, as it were, the space created by the extra people? And what if having only the two necessary people prevented that from ever happening?

Welcome to the federal – and most other – bureaucracies.

That is why bureaucracies grow in such an oddly non-linear, feedback loop way. The chicken begets the egg and the eggs beget more chickens and very soon – unless you eat them, which chicken and egg union rules say you cannot – you have far more chickens and eggs than you ever imagined or could ever possibly realistically use but they have to do something so you make something up for them to do.

Replace “chicken” with project or regulation and replace “eggs” with people and you have a rather apt metaphor for how a bureaucracy metastasizes.

Take the California Air Resources Board, for example. Created in the 1970s when the smog in LA was thick enough to be able to be spooned onto your ice cream, CARB set about their work and actually was rather successful.

For example, in 1980 Los Angeles had 80 “good/moderate” days of air quality and 159 days of “very unhealthy/hazardous” air quality. By 2021, those numbers had been more than turned upside down, with 269 “good/moderate” days and only one hazardous day in the year. In fact, the numbers showed vast improvement far earlier than that (as the standards were tightened over time, that one “hazardous” day would not have been deemed hazardous 25 years prior.) It should also be noted that smog has been a problem in the Los Angeles basin for, well, ever, with one of the worst smog days on record occurring in 1903 and Spanish conquistadors noting how the basin captured the smoke from the fires of the indigenous peoples.

Having solved its main problem CARB decided it had to continue to exist. Today, CARB is demanding trucks and boats and trains use technology that does not exist to meet “clean air” levels that have never existed, and even – really – has satellites, ‘fartniks,’ if you will, in space monitoring dairy farm methane levels.

Bureaucracies themselves become self-fulfilling prophecies of waste and pointlessness that use internal activity rather than the no-longer-possible meaningful external success as their only measure of success. Really – the air can only get so clean unless they eliminate modern society in its entirety and then people are dying of cholera when they are eight instead of cancer when they are eighty-eight so what’s the point?

The specific examples of bureaucreep are too numerous to list, but they can be delineated by type.

First, there is whim bureaucracy, most notably exemplified currently by the DEIists burrowing into every level of every bureaucracy.

They do not need to exist and many exist only to talk to other DEI people in other organizations. The entire concept is/hopefully-closer-to-was a political whim to stop people from asking electeds and executives whether or not the government and/or the company was “systematically racist.”

The higher-ups created an entire industry, an entire bureaucratic octopus, to not have to publicly answer the question (which is no, by the way) and possibly jeopardize their fleeting societal standing.

Second, there is the straight-up power play involving the creation of new regulations, strictures, and standards, putatively to help society and/or the bottom line but in fact only created to expand the power of the bureaucracy.

Third, there is an aspect often missed – ego. Government agencies do not turn profits (Tiny Fauci’s cabal excluded) so they must have some sort of metric to show the world how successful they as leaders are and that equation is “more activity + bigger staff headcount + larger budget = more important.”

Fourth, there is the savior concept. For some reason, many government and foundation leaders see themselves as saving the world, which makes them better than other people, while still being able to live quite well doing it. No monastic asceticism for them – I am doing well, therefore I must be doing good.

The regulatory process of the past 50 years started with some actually pretty necessary common sense notions – drunk driving is not actually cool, dumping toxic waste in salmon brooks might not be a good thing, smoking really can kill you so quit, don’t eat lead paint, etc.:

But these were the easy bits and the organizations and forces behind their implementation soon came to realize that if people started to be more sensible in general, society’s need for their input, expertise, and services – their guiding hand – would by definition decrease.

Take, for example, the March of Dimes. Originally started as an effort to both find a vaccine against polio and to help those already stricken, the organization in the early 1960s was facing a dilemma. With the vaccines pretty much eradicating the disease, the group was faced with a choice: declare victory and essentially close up shop or continue forward and not waste the fundraising and organizational skills and socio-political capital they had built up over the previous 20-odd years. They chose the latter and continue to this day as a very well-respected and important group, leading various initiatives to fight numerous childhood maladies.

Just not polio.

In the March of Dimes case, they unquestionably made the right call and they continue to serve a vital function. But to state that there were no, shall we say, personal motivations involved in that decision strains credulity.

This pattern – whether with good and righteous intent or not – was and is being repeated over and over again as lesser people and groups actively search out something – anything – that could theoretically possibly be misused or can even remotely be deemed questionable (everything is questionable – all someone has to do is ask the question) to latch onto and save us from.

Whether out of true concern or some other nefarious motive – power, profit, societal purchase – the inexorable march towards the bubble-wrap of today that was launched by the professional caring class continues all the way from the classroom to the living room to the newsroom to the board room.

Which brings us to today and the impending effort to control the federal bureaucracy.

To be successful, the DOGE must consider all of these factors to ensure a culture change that is as permanent as possible. It will not be enough to fire some folks and move on – Congress must write “tighter” laws, Schedule F – which allows for tippity-top bureaucrats to actually be fired for not doing their job – must be implemented, and an entirely new attitude must be instilled.

Government bureaucracies exist to collate, process, and to say no. Think about it – if the answer to a question was always going to be “Sure, why not?” then why would that job have to exist?

In fact, “Sure, why not?” should be the new default mode that the DOGE instills in the federal bureaucracy.

Of course, that idea can go too far:

Can I bury toxic waste next to the preschool? Sure, Why not?

EV cars are terrible but I’ve got a new engine that is powered by coal! Sure, why not?

And very “stakeholder” group will claim the above is exactly what will happen if even the tiniest change is made to the regulatory construct. Be forewarned – it will be all over what is left of the media.

The task is immense and very few efforts have ever been made to literally upend an existing bureaucracy wholesale and time will tell if the DOGE can pull it off.

But the DOGE must remember, at least, that the corollary to idea of “more people=more power” will most likely be true – “less people = less power.”

The bureaucracy will have to slough off its meaningless bits, the parts that only communicate with other bureaucracies, the parts that are paid to lie to the public, the parts that censor the public, and the fewer bureaucrats that are left around means the less chance they will invent new work for themselves.

Because now they will not be able to just hire people to do it – they’d have to do it themselves.

And we all know that is not going to happen.

Republished from the author’s Substack

Can DOGE Handle the Bureaucratic Imperative?

by Thomas Buckley at Brownstone Institute – Daily Economics, Policy, Public Health, Society

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: Brownstone Institute Read the original article here: https://brownstone.org/