Scarborough’s Grand Hotel isn’t so grand these days. Built in the shape of a V to honour Queen Victoria, this sandy-brick behemoth was billed as “the largest and handsomest hotel in Europe” when its doors opened in 1867. Edward VIII stayed here before ascending the throne. Sir Winston Churchill, the poet Edith Sitwell and Labour’s first prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald, were among the A-listers of yesteryear to visit this 12-floor wonder overlooking the North Sea.

When I arrive for my night at the Grand, my first impression is of the screeching seagulls and weeds that have been allowed to colonise the elegant roof with its four domed towers. Broken eggshells and droppings now pepper the walkways surrounding this once opulent building. A sign on a railing commands passers-by to “stop attacks” by not feeding the birds. Nearby, a dozen refuse bins and a cluster of tradesmen’s vans obscure the still striking entrance.

I’m not here for a holiday. This landmark on North Yorkshire’s coastline is my first stop on a tour of the extraordinary and fraying empire of one of Britain’s most secretive and intriguing property tycoons: Alex Langsam. The 86-year-old hotelier, worth at least £300 million, is spoken of as an enigma within the British property world; rivals who have spent decades in the hotel industry say they have never met him and don’t know anyone else who has.

How, then, has he made his fortune? His Britannia Hotels prides itself on offering “the best prices in the best locations”. A night in one his 63 establishments can cost as little as £27. Yet this is far from a British holiday miracle: for the past 11 years, the Cheshire-based group has been named as Britain’s worst hotel chain by the consumer research group Which?.

Even if you haven’t endured a night at a Britannia hotel yourself, you have indirectly contributed to Langsam’s riches if you are a British taxpayer. For many years his chain has earned well from Home Office contracts to house and feed asylum seekers. For which reason, the British tabloids have christened him the “Asylum King”.

Since 2011, this low-profile hotelier has also owned the Pontins holiday parks. After a flurry of closures late last year, only two resorts remain open of a group of five that has for decades held a special place in the hearts of many Brits. Famous for its “Bluecoat” entertainers, a cluster of stars have cut their comedic teeth at Pontins parks, including Shane Richie, Bradley Walsh and Lee Mack.

Those recent closures aren’t the only reason to wonder exactly what is going on inside the Langsam empire. Last summer the Royal Albion, a Britannia hotel on Brighton’s seafront, went up in flames. This was the latest in a series of fires at the group’s premises. A Britannia hotel in Aberdeen burnt down in 2016. Six years later, there were fires at other sites in Torquay and Manchester. There is no suggestion that these blazes were deliberate, but Which? has raised the quality of extinguishers, fire doors and other safety procedures on the Britannia estate.

Then there are concerns about the future of those lucrative Home Office contracts. Last year, the cost to the taxpayer of putting up asylum seekers in hotels was revealed to be £8.3 million a day. Though there may be no end to Britain’s migrant crisis, the Labour Party has pledged to end the use of asylum hotels. That can hardly be good news for Britannia’s finances. Might the state of Britannia’s buildings suggest Langsam’s group is already struggling?

***

When I step inside the Scarborough Grand, I am confronted by a sad jarring of the majestic and the kitsch. In honour of the European Football Championships, flag-themed bunting has been hung above the gold leaf central staircase. Beneath the central lobby’s classical arches and framed sepia photographs from the hotel’s golden age, I find a wall of fruit machines and a pool table. There’s the clatter of an air hockey table and vending machines dispensing Coke. Younger guests can plug pound coins into “Toy Tower” to get their hands on fluorescent cuddly toys. Yes, this Grade II*-listed building now has everything I would want from an amusement arcade.

The Adelphi is next on my list of Britannia’s tarnished gems. Built from Portland Stone and graced with recessed Ionic columns, this imposing pile in Liverpool’s city centre has been in Langsam’s hands for more than 40 years. Here is another building awash with history: guests over the decades have included Frank Sinatra, Bob Dylan and David Bowie. Liverpool-born songstress Cilla Black held her wedding reception here.

When I reach the Adelphi’s entrance, I am confronted by a large panel of MDF covering up the art deco revolving door. “Please take care, essential maintenance ongoing,” a sign explains.

A stroll around the hotel’s ground floor feels like stepping into the Thirties: there are marble floors, palm trees, chandeliers and a lead-lined glass ceiling. It’s not surprising that scenes from the BBC’s inter-war gangster saga Peaky Blinders were filmed here. Yet evidence of pinch-tight purse strings is all around. A swimming pool and gym in the basement has been out of bounds for more than five years. At times, there is no one behind the reception desk; it seems that anyone can come and go as they please.

Upstairs in my room, a 10-inch crack around the handle suggests my bathroom door has been forced. Perhaps maintenance is “ongoing” here, too. Though nobody has bothered to fix the broken shower.

“Did you get any sleep?” a weary young mum from Gloucestershire asks me at breakfast as we try to make sense of the toasters. During the night she, her husband and their two daughters were repeatedly woken by fellow guests returning from a rigorous night out in Liverpool’s city centre. “I’m on my knees today — so, so tired,” she says with a grimace.

Her experience sounds tame compared to the furious white-haired man I overhear at the reception desk. He and his wife are adamant there must be something wrong with the hotel’s key cards. Shortly after 2am, he says, another guest was able to barge into their room and relieve himself in their ensuite. “I snored all the way through it but he woke up my wife,” the man blusters. “The lad was all over the place. I don’t think he knew where he was.”

***

When I began my Britannia Hotels odyssey, I was initially surprised by how few of the company’s establishments I would actually be able to visit. The company’s online booking form showed that no rooms were currently available at 18 of its 63 premises. I later find out that these unavailable hotels are often those that have been used to accommodate asylum seekers. But the Home Office’s press team could not say exactly how many of Britannia’s hotels are currently block-booked on this basis.

The Britannia Hotel Hampstead is the first of these out-of-action hotels I visit. With its thin curtains and greying window frames, this seven-floor block near Chalk Farm’s tube station has the feel of a tired, Seventies student accommodation block. I spot a large rat trap around the lowest floor.

The sounds of workmen inside confirms what a caretaker behind the reception desk soon tells me: “The hotel is closed for refurbishment.” Yet a local estate agent says that at one point asylum seekers were certainly housed there. The hotel also acted as a shelter for homeless people during the pandemic, he adds.

The next day, I park outside the Airport Inn near Gatwick, another Langsam hotel that has also been used to accommodate asylum applicants. I have been there for just a few seconds before a security guard strolls across the car park and tells me that the hotel is now “private”.

Is anyone staying there at the moment, I ask? Neither the first guard nor a colleague who soon joins us will initially answer. After repeating the question, I am told the building is closed for a “refit”. As far as I can see there are no workmen or tradesmen’s vans in the car park. During the two-minute conversation before I am firmly asked to leave, I see a couple of young men smoking outside the hotel. Dressed in hoodies and jeans, they don’t look like plumbers, electricians or decorators.

A few days later I meet Ahmed Sami, a 28-year-old asylum seeker from Jordan, outside the Britannia Hotel Bournemouth. Sami is standing on the pavement while his room receives its weekly clean. He tells me he has been waiting three years for his asylum claim to be processed.

For the last three months, his home has been this scaffolding-clad hotel. When I suggest this sounds like a long time, Sami seems surprised. “Many people are here for two years, more even,” he says.

How is he finding Britannia’s accommodation? “It’s fine — we have TVs, every room has a bathroom,” he says. “There are three meals a day. Some people say the food is bad. So they have to go out to eat.

“The worst thing is there is nothing to do — it’s boring. We cannot work. Sometimes all we can do is sleep.”

Sami’s parents are still in Jordan and have been transferring money to him while he waits to hear if he will be granted indefinite leave to remain. “There are times when I have £60 to last the month.”

There are thought to be around 700 asylum applicants living in Bournemouth’s hotels. Most of them are men aged between 18 and their late twenties, many having made their way to the UK from Iran, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Afghanistan or Yemen.

Last November, the charity Refugee Support opened up a centre in Bournemouth providing clothing and other services to these asylum applicants. “We know of young men who have been in hotels here for up to three years,” says Zoe Keeping, the centre’s co-ordinator. “Often these are people who are suffering from PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] already.

“I wouldn’t say life in any of these hotels is good for your mental or physical health in the long-term. The men cannot work and so their lives lack routine. They have little money. Depression is common and there is an increased risk of suicide.” And yet, Keeping says, the hotels are arguably better than the alternatives: a detention centre or the Bibby Stockholm, the barge moored a few miles away in Portland Harbour used to accommodate asylum seekers. Last month, Labour announced that the barge will be closed in January 2025.

***

Alex Langsam knows what it is to be a refugee. In 1938, the year he was born, his Austrian homeland was annexed by Nazi Germany. He and his Jewish parents fled, taking the last train out of Vienna and leaving behind sizeable property and business interests.

On arriving in Britain, the young family was taken to an Isle of Man camp where hundreds of other Austrian and German Jews would spend much of the war. The Langsams would later begin to rebuild their lives from rented rooms in Hove on the Sussex coast.

Some 60 years later, in the only major newspaper interview Langsam appears to have ever given, the hotelier said that his mother and father would “probably have gone to the gas chambers” had they not been welcomed by Britain. “My father was the most nationalistic person I have ever come across,” the hotelier told The Guardian in that 2011 interview. “Britain saved his life and gave him a living and he instilled that in me. I am grateful for what this country has given me.”

Although Langsam failed his maths O-level, he was determined to study economics. Without that qualification, only Aberystwyth University was prepared to accept him. After graduating, Langsam started working as an estate agent. Before long he took up property development, launching a string of successful projects in Manchester.

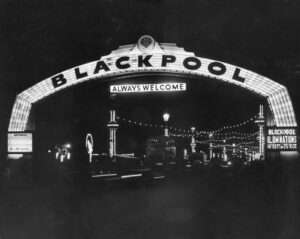

He bought his first hotel, the Country House Hotel in South Manchester, in 1976 when he was in his late thirties. He spent the next two decades on a buying spree, building a portfolio that soon spanned the UK. Today, there are six Britannia hotels in and around Manchester, five in Bournemouth, four in Blackpool and three in Leeds. Langsam has buildings everywhere from London to Llandudno and Aberdeen to Torquay.

The scarcity of staff and ropey maintenance I witnessed at the Grand and the Adelphi might have suggested Britannia’s finances are struggling. In fact, Langsam simply loves to run the tightest of ships. Annual profits at the group’s largest company have climbed by 18% to £39.4 million over the past year.

Three separate companies in the Britannia group now show net assets of more than £400 million. But a group structure involving a Jersey-based parent company and a trust ensures it is not possible for outsiders to see the full value of Langsam’s holdings.

His legitimate use of the soon-to-be wound down non-dom tax status has allowed him to pay less UK tax. But it has also provided a glimpse at the publicity-shy hotelier’s character.

Some years ago, Langsam launched a professional negligence campaign against the accountancy firm Hacker Young for not realising more swiftly that he could become a non-dom. Three days before the dispute was due to head to court, Hacker Young made a £1 million settlement to Langsam.

But that wasn’t the end of the matter. The property mogul later launched proceedings against the solicitors at Beachcroft who had represented him during the claim against Hacker Young. Why? Well, Langsam argued he should actually have received a £3 million settlement from Hacker Young — not a mere £1 million.

His claim against Beachcroft was lost but the judgement gives a feel for the way Langsam operates, describing him as a “large personality” who is “clearly used to getting his way and dominating those around him”.

The High Court judge who penned that judgement, Mr Justice Roth, watched the hotelier give evidence from the witness box for two days. During that time, the judge came to the view that Langsam had “now persuaded himself of a version of events” and convinced himself that his Beachcroft solicitor “was at fault on almost every occasion”.

“Either that has distorted his [Langsam’s] recollection or he deliberately embellished his account at various points to advance his case, or, as I consider more likely, there is some combination of the two,” Roth wrote.

***

A few days after my stay in the Adelphi, I drive to the East Sussex coast to see another bleak part of the Britannia empire: Pontins. When Langsam bought Pontins 13 years ago, he pledged to inject £25 million and some “razzamatazz” into the holiday park chain. “If you satisfy the kiddies, you satisfy the adults,” he said at the time, drawing parallels with the magic of Florida’s Disney World. “We believe there is a growing demand for traditional seaside holidays.”

As I arrive outside the Camber Sands park, a sign near the entrance lists pirate-themed crazy golf, go-karting and other amusements with “non-stop fun for all ages”. But the fun in fact stopped before Christmas last year when the resort was hastily closed. Dozens of staff lost their jobs; some said they were fired by text message. Two more Pontins sites at Prestatyn in North Wales and Southport on the Lancashire coast closed at the same time. A few hundred people were made redundant across the three sites.

When I stroll around the perimeter of the Camber Sands resort, I find there’s an eerie chill to the shuttered skatepark and holiday accommodation that once welcomed 3,000 visitors. The vast, lilac Pontins building looks weary and desolate.

A two-minute walk away I find what remains of Dunes, a restaurant and bar that did well from serving Pontins guests for nearly 20 years. Jimmy Hyatt, the owner, said the resort’s closure proved a “devastating loss”. In April he wound up Dunes. Sugar Rush Treats, a confectionary and ice-cream store nearby, also shut up shop at the same time.

“It’s sad, it really is,” says Paul Osbourne, a Conservative councillor for Camber. “Pontins used to provide a very cheap holiday for those who otherwise wouldn’t have been able to afford it. I’m sure it was heaven for people escaping cities… But it hasn’t been great for some years.”

What now for Camber’s Pontins? There was a short-lived plan to convert it into a centre to house asylum seekers. However, the land is owned by Rother District Council, and a legally-binding clause in the lease ensures it can only be used as a holiday park. Several buyers have offered to take on the site and it is understood that the council is examining the lease to see if Britannia has breached its terms.

***

What would Langsam think of all this? We don’t know. As is its custom when dealing with the media, Britannia declined to respond to repeated enquiries for this article. I’m told by someone familiar with Britannia that criticism from journalists is “water off a duck’s back” for Langsam.

That said, it seems naive to point the finger at Langsam for Britain’s shattered seaside economies or for earning well from asylum contracts. It was the advent of budget airlines in the Eighties and Nineties that really made vast luxury hotels in Britain’s coastal resorts financially unsustainable. Why play roulette with the English weather when an easyJet flight from London to Mallorca can cost less than £15? What’s more, it was the Government that approached Britannia asking the group to accommodate hundreds of migrants. Surely, then, Westminster is to blame, rather than a businessman ultimately trying to address the shortage of adequate refugee accommodation?

There is also no doubt that the cost of maintaining historic buildings has ballooned in recent years. Listing regulations often place an obligation on owners to preserve great buildings as they were many lifetimes ago. Such rules can be expensive, obstructive and impractical for a hotelier trying to keep these buildings alive in the 21st century.

Keeping investment low also makes it easier for Britannia to ensure their room rates can be kept at bargain prices, thereby allowing those with stretched budgets to enjoy a holiday. And it’s true that the chain’s premises often work out at between half and two thirds of the cost of rival budget hotels in the same cities. Indeed, Langsam has claimed that his “extraordinary buildings” are “enjoyed by ordinary people”.

Then again, thousands of Britannia guests don’t feel they “enjoyed” their time in his hotels. More than 4,350 of almost 9,000 Tripadvisor reviews of the Adelphi judged their visits as either “poor” or “terrible”. On the same platform, the Scarborough Grand fairs even worse, with more than half of the 10,171 reviews rated in those bottom two categories.

And yet, as consumers, don’t we accept that often in life we get what we pay for? If we are stumping up just £27 for a night at a Langsam hotel — as one can at the Cavendish in Eastbourne — can we really be astonished if it doesn’t turn out to be the Ritz?

That argument doesn’t wash with Christine Bayliss. A former civil servant now responsible for economic development in the vicinity of the Camber Sands Pontins, Bayliss says: “Just because something is cheap, doesn’t mean it’s good value.

“We had complaints about the quality of the Pontins for years before it closed. I stayed in a Britannia hotel in Manchester — it was awful. You’ve seen the same for yourself. I hate the sweating of assets like this. Honestly, this is the sort of capitalism that gives capitalism a bad name.”

But perhaps the problem is not too much capitalism — but too little. Over the course of this investigation, I have spoken to numerous frustrated property developers, politicians and other local community leaders who have found dealing with Britannia utterly maddening. Those who would like to take on Langsam’s tired sites and breathe new life into the surrounding communities are ignored. Britannia has a reputation for not engaging with emails and letters from outsiders seeking to buy its premises.

So incensed by this aspect of Langsam’s business, Keane Duncan, the Conservative candidate in this year’s election for a new mayor of North Yorkshire, even spoke of using public funds to acquire the Scarborough Grand — though his party hardly has a history of state appropriation of privately-held assets.

“I admit this is a radical plan,” said Duncan, who ultimately failed to win the election. “But tackling the problem of the Grand is absolutely essential for Scarborough’s future fortunes.”

Now in his mid-eighties, Langsam remains at Britannia’s helm. He lives alone and quietly in a 10-bedroom former hotel in Cheshire. Unmarried and without children, work continues to dominate his life as it always has.

A few days after my return from Camber Sands, my phone rings. At long last it seems I have found someone who knows Langsam and is prepared to offer the hotelier’s side of the Britannia story.

“I like and admire Alex Langsam very much,” this person says, speaking on the grounds of strict anonymity. “He is entirely self-made, incredibly hardworking. Our country needs more people like him — not less. It’s amazing what he’s achieved during his life.

“Yes, he has been criticised for providing accommodation for migrants but this was after all at the specific request of our government. They have to live somewhere.”

This person reminds me that Langsam and his parents were once refugees. “He continues to be very grateful to the UK for saving their lives and is well placed to sympathise with the position of migrants today,” he adds.

“I suspect the fact that so many of his family were murdered in the Holocaust continues to motivate him to this day. I couldn’t say what will happen to his fortune when he dies but I suspect it will all go to charities that help others who have suffered from tragedy in their lives.”

That would be quite a legacy. It’s perhaps a better one to dwell on than the sad decay of what were once some of Britain’s most glamorous hotels. Or, for that matter, the discomforting thought that buildings little different to those besieged during this summer’s wave of protests and riots have for many years proved a pretty damn fine investment.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/