“In reality we know nothing; for the truth lies in the abyss.”

ἐτεῇ δὲ οὐδὲν ἴδμεν: ἐν βυθῷ γὰρ ἡ ἀλήθεια.

These words were spoken, it is said, by Greek philosopher Democritus, to which attests Diogenes Laertius in his Lives of Eminent Philosophers.

The Greek word bythôi (βυθῷ), a form of “bythos” or “buthos” (βυθός), implies the depths of the sea and is usually translated as “depths” or “abyss;” but Robert Drew Hicks used the term “well:”

“Of a truth we know nothing, for truth is in a well.”

He may have taken a bit of poetic license, but the basic idea seems intact. For a well, like the depths of the sea, is a kind of dark, aqueous abyss; and it seems like an equally apt metaphor as a hiding place for the Truth.

Yet, it might be a slightly more sinister hiding place. On the one hand, Truth as hidden in the ocean is a natural mystery to be uncovered; after all, man still hasn’t fully explored its depths. On the other hand, a well is a man-made artifice; if Truth lies hidden down there, she was most likely pushed or thrown.

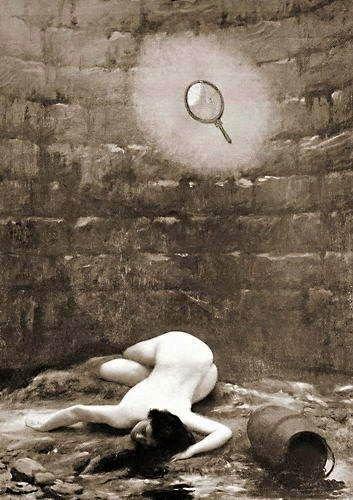

And there she is, above, as if to prove this point, depicted in an 1895 painting by the French artist Jean-León Gerome. He captioned it with the sobering mouthful:

Mendacibus et histrionibus occisa in puteo jacet alma Veritas (The nurturer Truth lies in a well, having been killed by liars and actors).

He could have painted it yesterday, for the moment I laid eyes upon it I recognized the vivid representation of our current reality. And as for the title, though it may be long, you’d be hard-pressed to come up with a better summary of the world post-Covid.

The beautiful woman is naked — as in “the naked truth” — and this is fitting, for the word Democritus used — aletheia (ἀλήθεια or άληθέα) — etymologically implies a lack of perceptive ignorance. It is the absence of lethe (ληθή), “forgetfulness” or “oblivion,” which itself derives from the verb lanthánō (λανθάνω), “to escape notice or detection.” According to Alexander Mourelatos, writing in The Route of Parmenides:

“The literal and precise English translation would be ‘non-latency’.”

Heidegger translated aletheia as Unverborgenheit or “unconcealment;” but this neglects the active component of perception.

As German classical philologist Tilman Krischer explains in “ΕΤΥΜΟΣ und ΑΛΗΘΗΣ” [Etumos and Alethes]:¹

“When interpreting the word, one should not abstract from the act of perception but rather assume that such an act takes place and is realized without impairment through possible ‘oversight.’ It is not enough for an object to be αληθής [alethes] (truthful) that a curtain of concealment has been figuratively removed from it [. . .] Rather, the object must be thoroughly investigated [. . .] In accordance with this result, the expression άληθέα ειπείν [aletheia eipeín] (to speak the truth) can be paraphrased as follows: ‘to make a statement so that the object does not go unnoticed (i.e., is perceived without impairment).’ It is not the state of being veiled or covered that is negated but rather that lethe (oblivion), which also causes immediate perception to become incomplete. Not going unnoticed imposes higher demands on the speaker than mere ‘unconcealment’ [. . .] It is not enough for the speaker to uncover the object; he must show it precisely and draw attention to the details; only in this way can he prevent anything from escaping the attention of the addressee.”

Aletheia as “truth” does not refer to a collection of objective facts (although it depends on the speaker’s knowledge of the facts in order to be realized).² It is not synonymous, therefore, with mere factual “reality.” Nor is it simply a revelation of the hidden. Rather, it implies a conscious attempt by a knowledgeable witness to draw meticulous attention toward something that previously went unnoticed, or that escaped from observation; and this, in a way that paints a holistic, faithful, and undistorted representation of its object.

We can sketch this definition along three main facets:

1. Aletheia is not a label to be slapped on information, objects, or events, but the fruitful result of a process that is inseparable from the speech-act (and thus, also, from its source).

2. That process invokes a complete and active methodology, beginning from the original moment of observation and ending with the successful communication of that observation to the intended recipient(s).

3. The result of that process is the removal, or absence of lethe (oblivion).

This nuanced and specific approach to the idea of “truth” differs greatly from the one that we are used to. We tend to think of truth as a sort of conceptual object that can be “discovered” in the world outside ourselves; and, once “discovered,” theoretically, can be passed around or traded ad libitum.

While most of us acknowledge that the source transmitting this “object” can potentially distort or influence its presentation, we don’t usually think of truth itself as a phenomenon contingent on the skillful observation and communication of the person or source who relates it.

But we live in such a complex world that almost everything we think of as “the truth” comes down to us, not through our own experience, but through stories told to us by other people. And many of these people are themselves removed by several links from the original source that made the observations.

This situation is highly susceptible both to contamination through error and to conscious manipulation by people with opportunistic agendas. Since we cannot verify every statement made about our world through independent observation, we must decide whether or not to trust the witnesses and sources we rely on. What happens if these people are not talented observers or communicators, or if it turns out they cannot be trusted? And, furthermore, how would we go about determining whether or not that is the case?

Adding to this problem, there are so many reports available to us purporting to divulge the nature of reality that we cannot possibly absorb them all in detail. Instead, we tend to consume isolated facts about disparate subjects, and we often take those facts as representative of the entire picture until proven otherwise. This positivistic approach to reality encourages us to lose sight of the holes in our knowledge, and to construct our images of the world at a lower resolution.

We have access today to more information from more parts of the globe than we have had at any previous point in human history, and we spend hours every day perusing it; but for all that, our ability to meaningfully absorb and verify what we take in seems — if anything — to have diminished. And yet, somehow, it seems the more that we lose contact with our ability to know what’s real, the more intractable we grow in our opinions, and the more we cling to the spurious conviction that we understand the complex world we live in.

It’s no wonder, then, that, on a collective level, we sense that our relationship with truth is breaking down.

The notion of aletheia, by contrast, highlights the potential for ignorance or error to obscure the truth at each stage of the process of relating information. It draws attention to the frontier spaces where our certainty dissolves, and focuses our gaze on them. It thus reminds us where our blind spots are, and invites us to consider the possibility that we might be wrong or lack important context.³

It is precisely this notion that seems to have been lost in today’s social environment. The beautiful Lady Aletheia lies at the bottom of a well, having been thrown there by liars and actors. Because scammers and charlatans — whose success depends on claiming a monopoly on truth — always have a vested interest in obscuring the frontiers of their knowledge and the realities behind their distortions.

If a source of information refuses to explore these boundaries, dismisses skepticism, or insists that all dialogue must stay within a predetermined window of “correctness,” this is a major red flag that they cannot be trusted. For it is at the often-controversial limits of our knowledge that the truth tends to reveals itself as chaotic and complex, and it becomes impossible for any single faction or individual to monopolize the narrative surrounding it.

What might we learn about our relationship to truth today if we attempt to resurrect Aletheia? Can this concept, lost to time, known to us only from the earliest Greek texts, help us restore a sense of clarity and open-mindedness to discourse? Below I will explore each of the three main facets that characterize this approach to thinking about truth, and the implications for our own attempts to reach a common understanding of veracity today.

1. Aletheia is Linked to Speech

As mentioned earlier, aletheia does not denote the truth about an objective, external reality. For this, the ancient Greeks used the word etuma (ἔτυμα, “real [things]”) and its relatives, from which we derive the word etymology (literally, “the study of [a word’s] true sense, original meaning”). Aletheia, by contrast, is a property of speech, and therefore rests on the communication skills of the person doing the speaking.

As Jenny Strauss Clay observes, analyzing the poet Hesiod’s use of these terms in Hesiod’s Cosmos:

“The difference between ἀληθέα [aletheia] and ἔτυμα [etuma], while often ignored, is crucial not only for [the passage in question], but for Hesiod’s entire undertaking. Aletheia exists in speech, whereas et(et)uma can inhere in things; a complete and accurate account of what one has witnessed is alethes, while etumos, which perhaps derives from εἴναι [einai] (“to be”), defines something that is real, genuine, or corresponds to the real state of affairs [. . .] Etuma refer to things as they really are and hence cannot be distorted; aletheia, on the other hand, insofar as it is a full and truthful account, can be willfully or accidentally deformed through omissions, additions, or any other distortions. All such deformations are pseudea [falsehoods].”

Here Clay is writing in reference to a passage (below) from Hesiod’s Theogony, which, along with Works and Days, the anonymous Homeric Hymns, and Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, ranks among the oldest surviving works of Greek literature. The thousand-line poem, dating from around the 8th century BCE, relates the story of the origin of the cosmos and the genealogy of the immortals.

Of course, the birth of the gods and the creation of the universe are grand events that no mortal being can claim to relate with absolute certainty, because no mortal being was there to observe them happen. So the question naturally arises: how does Hesiod know that the story he recounts is true?

The answer is: he doesn’t, and he makes his audience aware of that immediately. He does not present his story as incontrovertibly factual; rather, he frames his entire narrative in the context of something he can theoretically verify: his own personal experience. He openly reveals the layers that lie between his audience and the events that he describes: namely, both himself and the original source of his information, the Muses, whom he claims to have encountered at Mount Helicon: [translation and bracket commentary by Gregory Nagy]

“[It was the Muses] who taught me, Hesiod, their beautiful song. It happened when I was tending flocks of sheep in a valley of Helikon, that holy mountain. And the very first thing that the goddesses said to me, those Muses of Mount Olympus, those daughters of Zeus who holds the aegis, was this wording [mūthos]: ‘Shepherds camping in the fields, base objects of reproach, mere bellies! We know how to say many deceptive things looking like genuine [etuma] things, but we also know how, whenever we wish it, to proclaim things that are true [alēthea].’ That is how they spoke, those daughters of great Zeus, who have words [epea] that fit perfectly together, and they gave me a scepter [skēptron], a branch of flourishing laurel, having plucked it. And it was a wonder to behold. Then they breathed into me a voice [audē], a godlike one, so that I may make glory [kleos] for things that will be and things that have been, and then they told me to sing how the blessed ones [makares = the gods] were generated, the ones that are forever, and that I should sing them [= the Muses] first and last.”

Hesiod, a lowly shepherd and “mere belly,” derives his authority to speak about this subject from the Muses, who are divine beings. As such, they can access secrets of the universe that are unavailable to mortal men.

Yet, despite their elevated status, immense wisdom and their technical advantage, the Muses still cannot be trusted to proclaim the truth [aletheia, tied to the speech-act] — they are capricious and they have their own agendas.

They certainly know how to do so, whenever they wish it, but they also know how to tell many falsehoods [pseudea polla] that resemble truth [that is, resemble ‘genuine things’ in the objective and external sense, represented by a form of “etuma”]. And we mere mortals cannot hope to tell the difference.

Clay elaborates:

“In drawing attention to their capricious nature, the Muses reveal themselves to share a trait that elsewhere too characterizes the attitude of the gods vis-à-vis the human race. If the Muses have the capacity to declare the truth, if they want, we mortals cannot know when they do so, nor can we distinguish their lies from their truths [. . .] The words of the smooth-talking (ἀρτιέπειαι, 29) Muses address to Hesiod put us on notice that we too cannot distinguish the truth in what follows, that is, in the Theogony itself. While Hesiod may well be the Muses’ spokesman, and the voice (aude) that they breathed into him possesses their authority, nevertheless, he does not and cannot guarantee the absolute truth of his song [. . .] And no wonder: the things recounted in the Theogony, the origins of the cosmos and the gods, are beyond human ken and hence unverifiable.”

The Muses have the capacity to speak aletheia; but sometimes — and, likely, often, for various reasons — they simply don’t. We can draw several parallels here between Hesiod’s predicament in Theogony and our own predicament thousands of years later.

In today’s world, scientific and rational materialist narratives have largely taken over the role of cosmogonic storytelling. By that I don’t just mean our stories about the origins of the universe itself: I mean, also, the origins of the entire structure of the world we now occupy. For this reality, once composed primarily of natural ecosystems and forces, has come to be dominated by the technical artifices of Man.

Where did these institutions and the constructed landscapes we inhabit come from? Why do we do things the way we do? Who creates the systems and objects with which we interact, and on which we depend for our survival? No mortal being alive today has witnessed the totality of this vast infrastructure.

So we must rely on puzzle pieces gleaned from other people for our understanding of the world’s origins and inner workings — perhaps, not divine beings or Muses but, increasingly, authorities and experts who can be equally capricious. Like the Muses, these scientific and institutional authorities have immense technical advantages relative to the average person, which allow them, theoretically at least, to access cosmic secrets that no ordinary mortal can.

However, unlike the Muses, they themselves are mortal, and lack the inherent wisdom and excellence one might expect from divinity. Their capriciousness, therefore, is all the more dangerous: it can extend into the realm of outright corruption and even perverse evil. But because of the technical differential that exists between these institutions and authorities and the average person, ordinary people often can’t distinguish between their true utterances and their mistakes or falsehoods.

Most people invoke pragmatism in response to this assertion. Sure, it is impossible to personally verify many of the “facts” about the world that we encounter; but if we can’t allow ourselves to place our faith in anything that we don’t witness for ourselves, we run the danger of denying very clear and practical realities. We don’t always need to be able to observe things for ourselves in order to have confidence in their solidity.

But there is a converse tendency to move from tentative acceptance of a seemingly straightforward truth to a dogmatic and closed-minded obstinacy. By divorcing the idea of truth from the speech-act and thus from the person doing the speaking, we can easily lose sight of the uncertainty that always overshadows our reliance on other observers — with their biases, their moral flaws and limitations — to recount to us an accurate picture of reality.

The fragility and vulnerability of the systems and the people we depend on disappears, little by little, into the background, and this provides an ideal environment for opportunists who decide they want to pass off spurious claims and outright lies as obvious, unquestionable dogma. And this is the slow road to a world where supposed “doctors’” and “biologists” deny realities as blatant and independently verifiable as the difference between “male” and “female” — and where many people actually take them seriously.

So what is the process that takes place during speech that determines whether or not something is aletheia?

2. Aletheia is Truth and Method

To speak aletheia is not the same as uttering factually correct statements. It is not enough to know something — or to think you do — and then repeat it; speaking aletheia is an active process that begins with personal observation.

This point is important: aletheia is associated with eyewitness reports — the kind of report a detective or a good journalist might make. Those who speak aletheia report, usually, from their own, personal experience: they observe, in meticulous detail, the environment around them, trying to absorb as much nuance as possible. As soon as even one layer is introduced between the storyteller and the person who witnesses an event, its qualifications for being alethes are called into question.

Tilman Krischer tells us:

“In the Odyssey, ἀληθής [alethes] and ἀληθείη [alēthēíe, alternative spelling of aletheia] occur together 13 times (the noun exclusively in conjunction with the verb καταλέγειν [katalegein, “to enumerate” or “recount”]). In most cases, it involves situations where someone reports on their own experiences. For example, in 7, 297, Odysseus tells Queen Arete about his shipwreck. In 16, 226ff, he tells Telemachus how he arrived from the land of the Phaeacians to Ithaca. In 17, 108ff, Telemachus reports to Penelope about his journey to Pylos. In 22, 420ff, Eurykleia informs Odysseus about the behavior of the maids. When in 3, 247 Nestor is asked by Telemachus to report ἀληθής [alethes] about the murder of Agamemnon, which he certainly did not witness, and Nestor subsequently promises to speak ἀληθέα πάντ᾽ ἀγορεύσω [to proclaim the whole truth] (254), it is evidently a borderline case. Nestor provides a lengthy account of events he personally experienced; however, in contrast with Telemachus, he is well-informed about the rest [. . .] The scope of ἀληθής [alethes] is essentially limited to eyewitness accounts, where the speaker speaks from precise knowledge and only needs to ensure that no slip-ups occur. On the other hand, if a statement is referred to as ετυμος [etumos], it does not matter where the speaker obtained their information: they may have made assumptions, had dreams, made prophecies, or sprinkled truths into a lie — what matters is that it is ετυμος [etumos, ‘real’].”

A statement cannot be alethes if it is too far removed from the realm of personal experience. But the true key is a sense of meticulous attention, applied in a holistic way: someone who did not experience something can potentially still speak aletheia about it if they are precise, thorough and well-informed; on the other hand, even personal experience can’t properly be called alethes if it is incomplete or contains assumptions or inaccuracies.

We can see this emphasis on holistic precision reflected in the fact that, in the works of Homer, aletheia is often paired with “katalegein” (from which we derive the word “catalogue”). According to Krischer, katalegein “exclusively denotes the factual and precise presentation that goes through the subject point by point”, specifically, in the context of providing information.

One must first intricately observe a situation or event, inspecting every angle; then, one must proceed to reproduce these observations for a naïve audience in an equally precise and ordered way. Attentiveness to detail is important, then, just as much when witnessing events as when deciding how to frame and craft one’s narrative.

The result should be a balanced microcosmic sketch of what one witnessed, so that no relevant aspect goes unnoticed. However, in order for this picture to come across to its recipient with clarity, it is also important not to include too many irrelevant or distracting details, or to embellish one’s tale with personal projections or fantasies.

As Thomas Cole writes in Archaic Truth:

“There are [. . .] contexts where it is not freedom from omissions but just the opposite — freedom from irrelevant or misleading inclusions — that [aletheia] seems to designate. Such inclusions, in the form of encouraging but ill-founded leads on the whereabouts of Odysseus, are probably what Eumaeus has in mind when he says that travelers are unwilling alêthea mythêsasthai [unwilling “to speak the truth”] in the tales they tell Penelope (14,124-125). The pseudea [falsehoods] (ibid.) which result are not simply untruths but, as Eumaeus himself indicates three lines later (128), elaborate fabrications: no one confronted, as the travelers are, with the prospect of being rewarded for any good news he brings can resist the temptation epos paratektainesthai [to spin up their tales]. Priam may be on his guard against similar elaborations — as well as tactful omissions — when he asks Hermes (disguised as a servant of Achilles) for pasan alêtheiên [the whole truth] (Il. 24,407) on the fate of Hector’s body [. . .] What is involved is strict (or strict and scrupulous) rendering or reporting — something as exclusive of bluster, invention or irrelevance as it is of omission or understatement.”

In order to successfully speak aletheia, the speaker must practice skill and accuracy both in observation and articulation. They must take in a well-rounded and proportional overview of a situation, while maintaining the precision necessary to absorb nuance and detail about minute particulars.

They must not exaggerate any particular or favored point over relevant others, create caricatures or sculpt their tales to fit their biases or expectations; and they must not include embellishments, project their own assumptions, or include imagined or hypothetical elements as fact.

To “speak aletheia” is the difficult art and science of meticulously crafting an image of observed reality that does not distort or deviate from its original form. And if this reproduction is faithful, balanced, clear, and sufficiently detailed, then — and only then — can it be called aletheia.

This process may sound very similar to the idealized version of the scientific method, or to the techniques we associate with good, old-fashioned, professional journalism. Indeed, we probably hope our scientists and journalists are doing exactly this as they make their observations on the oft-elusive niches of reality they investigate, and then disseminate their findings.

But is this actually happening, in practice? Increasingly, evidence suggests that the reality, in many cases, bears little resemblance to this utopian ideal.

Alan MacLeod, an investigative journalist and former academic whose research specializes in propaganda, describes one such scenario in his book Bad News from Venezuela. MacLeod spoke with 27 journalists and academics about their experiences covering Venezuelan politics. He concludes:

“Virtually all the information that British and American people receive about Venezuela and South America more generally is created and cultivated by a handful of people [. . .] As news organizations try to trim their payroll and cut costs, they have become increasingly reliant on news wire services and local journalists [. . .] As a result, ‘news’ appearing in print is often simply regurgitated from press releases and wire services, sometimes rewritten and editorialized to different perspectives but often literally verbatim (Davies, 2009: 106-107) [. . .] For example, The New York Times regularly republished Reuters newswires verbatim, whereas The Daily Telegraph did the same with both Reuters and AP [. . .] Increasingly, stories about Venezuela are being filed from Brazil or even London or New York. The kind of insight a reporter could have from those locations is debatable. Correspondents who are stationed in Latin America are instructed to cover multiple countries’ news from their posts. Two of the interviewees lived in Colombia and only rarely even visited Venezuela. One lived in the United States [. . .] In terms of foreign correspondents, [Jim Wyss, of The Miami Herald] said for major English-language newspapers, only The New York Times has one in Venezuela. There are no full-time correspondents stationed in Venezuela for any British news source. It follows that, for the entirety of the Western English-language press, there is only one full-time correspondent in Venezuela. Consequently, there is a lack of understanding of the country.”

MacLeod found that journalists were often sent for only brief stints to the country and lacked appropriate background knowledge of its cultural contexts and history. In many cases they couldn’t speak Spanish, either, precluding them from communicating with all but the top 5-10% percent of the wealthiest and most educated inhabitants. They were housed in the wealthiest, most insulated districts of the nation’s capitaol and were often connected with their interviewees by third parties with political agendas. How could anything resembling a nuanced, detailed, and holistic account of reality result from such a process?

Adding to this problem are the often tight deadlines imposed on reporters for crafting their narratives. Bart Jones, a former Los Angeles Times journalist, confessed:

“You have got to get the news out right away. And that could be a factor in terms of ‘whom can I get a hold of quickly to give me a comment?’ Well it is not going to be Juan or Maria over there in the barrio [local neighborhood] because they don’t have cell phones. So you can often get a guy like [anti-government pollster] Luis Vicente Leon on the phone very quickly.”

MacLeod writes:

“This raises the question of how can a journalist really challenge a narrative if they have only a few minutes to write a story. In the era of 24-hour news and Internet journalism, there is a heavy emphasis put on speed. This emphasis has the effect of forcing the journalists to stick to tried and tested narratives and explanations, reproducing what has come before. The importance of being the first to print also means that journalists cannot go into detail either, leaving the content both shallow in terms of analysis and similar to previous content.”

Instead of questioning simplistic assumptions, delving into the nuances of often intricate and deeply-rooted sociocultural dynamics, and investing the years’ and perhaps decades’ worth of time and attention necessary to obtain an accurate and balanced picture of complex realities, journalists often merely end up cloning previously-published narratives from one-sided perspectives in a cartoonish fashion. And it is this that is then fed to us as representative of objective reality, and that many people accept uncritically as “truth.”

Under such conditions it doesn’t matter much if someone takes their news from a variety of sources or political biases; the information ultimately originates from similar places and is framed by similar perspectives.

According to MacLeod, the editors of publications often move in the same social circles; journalists themselves tend to come from fairly homogeneous backgrounds, and share political viewpoints; they often end up stationed in the same locations, gathering data from the same informants; and in fact, many of the reporters who maintain a façade of opposition to each other or who work for politically opposed publications end up sharing contacts and attending the same parties and events.

Any information that is gleaned from circumstances like these, and then presented simplistically as “truth,” will almost certainly tend to increase lethe, rather than removing it.

3. The Removal of Lethe

A speech or communication that is worthy of the term “aletheia” results in the “removal of lethe.” This lethe, or oblivion, that is removed refers to the oblivion that always threatens to arise whenever a firsthand witness tries to pass on observations to an audience who wasn’t there. It is an oblivion of the truly objective reality of a situation, an oblivion that is caused by the inevitably incomplete and imprecise process of filtering the world through our biased and limited minds — and from there, out into the dicey realm of spoken word.

To speak aletheia successfully is to possess the ability to recount that witnessed reality with such fullness and clarity that the listener can perceive it — secondhand — with as much detail and accuracy as if they had been there, themselves, in the first place.

But there is also another kind of “removal of lethe” implicit in the use of the word aletheia: for, since aletheia reminds us, by its very name, that oblivion and distortions of reality can infiltrate at each node of the communication process, the term itself invites us to remove our own oblivion about exactly where the limitations of our knowledge lie.

The notion of aletheia draws our attention to the precise points in that process where our certainty breaks down, and this allows us to “geolocate” our position, so to speak, within a sort of holistic cartography of truth. By delineating the precise boundaries of our own perspective and our comprehension, we can build a solid picture of our knowable reality while remaining open-minded about the things we might not fully understand.

We can see this metafunctionality of the word aletheia in action even as its usage starts to change, in later works. Tilman Krischer tells us:

“In Hecataeus of Miletus, who is significantly influenced by Hesiod, the framework of epic language is transcended, but the new [usage] can be easily explained from the old roots. When he writes at the beginning of his Histories (Fr. 1), τάδε γράφω ώϛ μοι δοκεΐ άληθέα είναι [I write these things as they seem to me to be truth/aletheia], the combination δοκεΐ άληθέα [dokeî aletheia, “seems (like) truth”] indicates the departure from the epic. Where aletheia is limited to providing information about one’s own experiences, such a δοκεΐ [dokeî, “seems (like)”] has no meaning. Hecataeus’ aletheia, on the other hand, comes about through ίστορίη [historíē, “systematic inquiry”] that is, through the combination of information from others. The writer deduces the aletheia from the information he receives, and it is only consistent for him to say that it seems to him to be άληθέα [aletheia]. The ίστορίη [historíē] as a methodical inquiry allows for expanding the originally very narrow scope of aletheia arbitrarily but at the cost of a lesser degree of certainty. The δοκεΐ [dokeî] expresses the critical awareness that the full aletheia cannot be achieved through ίστορίη [historíē].”

Hecataeus’ history — now available to us only as scattered fragments — was built from various accounts systematically compiled from other sources; although he tried his best to sort the trustworthy versions from the dubious, he nonetheless acknowledges that he cannot completely guarantee aletheia.

The word itself invokes its own criteria, and Hecataeus manages to preserve its integrity by qualifying his statement with an appropriate degree of uncertainty. He did not witness the events he writes about; therefore, the most he can say about them is that they “seem to [him] to be truth”.

“Aletheia” is not a term to be thrown around or used lightly; it holds us to a high standard, and invites us to constantly remember the gap between our own best efforts to know reality and the ever-unreachable ideal of perfect certainty. Its proper use should therefore humble us in our search for knowledge and understanding, allowing us to approach opposing viewpoints with a sense of curiosity and with an open mind.

For even under the best of circumstances, it is difficult to know for sure whether one is speaking aletheia oneself, and even more difficult for a person on the receiving end of information to know for sure whether their source is doing so. According to Thomas Cole:

“It is possible to know on the basis of one’s own information that a particular statement is etymos, or even that it is unerringly so [. . .]; but to be in a position to judge the [. . .] alêtheia of anything more elaborate than a brief statement of present intention [. . .] implies prior possession of all the information being conveyed. And this will normally exclude needing or desiring to hear the speech at all.”

Yet embracing the notion of aletheia does not necessitate a nihilistic view of knowledge: it does not require us to conclude that we cannot possibly know anything and to give up on the pursuit of truth entirely. It just requires us to move beyond a purely binary approach to knowledge, where all “facts” we come into contact with are stamped as either “accepted” or “rejected.”

Aletheia is a sort of “analog” approach — a vinyl record or 8-track, if you will — to seeking truth, as opposed to a CD or digital recording represented only by a series of ones and zeroes. It allows for the existence of degrees of confidence based on our personal proximity to the experience of the events we’re dealing with.

What if our experts and authorities, back in 2020, had used this approach, instead of jumping to claim absolute certainty and then imposing this certainty on the entire global populace?

What if they had said, “Lockdowns might save lives, but since these are incredibly draconian measures that have never been imposed before on such a scale, maybe we should consider those proposing alternative solutions?”

What if they had said, “It seems like these experimental vaccines show promise, but since they’ve never been tested on humans, maybe we shouldn’t coerce people into taking them?”

Could we have had a calm and truly open dialogue as a society? Could we have made more reasonable choices that didn’t impose vast amounts of suffering on millions and perhaps billions of people?

But they didn’t do this, of course. And to me, as I watched governments impose unprecedented restrictions on basic human freedoms around the world beginning in February of 2020, the telltale sign that these experts and authorities were not acting in good faith was that — before any reasonable person would declare they knew what was happening — they rushed to say, “We know the truth with certainty, and anyone who questions our judgment is spreading dangerous misinformation and must be silenced.”

No one who has ever uttered such a phrase, in the history of mankind, has ever had pure or benevolent intentions. Because those are the words that, without fail, end with aletheia cast into a well — usually to the benefit of those who have a vested interest in promoting lethe or oblivion.

In Greek mythology, the River Lethe was one of five rivers in the underworld. Plato referred to it as the “amelēta potamon” (the “river of unmindfulness” or “negligent river”). The souls of the deceased were made to drink from it in order to forget their memories and pass to the next life.

In a similar way, those who aim to reinvent society from the top down rely on our unmindfulness and our oblivion – both to the nature of actual reality, as well as to the fact that we are being cheated and manipulated. They need us to put our trust in them on autopilot, accepting whatever they tell us as “fact” without asking too many questions. And they rely on us forgetting who we are, where we came from, and where we stand in relationship to truth and to our own values and history.

Over the past few years, liars and actors have tried to make us forget the world we once knew and have inhabited all our lives. They have tried to make us forget our humanity. They have tried to make us forget how to smile at each other. They have tried to make us forget our rituals and traditions.

They have tried to make us forget that we ever met each other in person rather than through an app controlled by a third party on a computer screen. They have tried to make us forget our language and our words for “mother” and “father.” They have tried to make us forget that even as recently as a few years ago, we did not shut down entire societies and lock people indoors because of seasonal respiratory viruses that — yes — kill millions of people, mostly the elderly and immunocompromised.

And who benefits from all of this “forgetting?” Vaccine manufacturers. Billionaires. Pharmaceutical companies. Tech companies that provide the technology we now are told we “need” in order to interact with each other safely. Governments and bureaucrats who acquire more powers than ever over the lives of individuals. And the authoritarian elites who benefit from the all-too-obvious effort to redesign the infrastructure and culture of our society and the world.

If these scammers and charlatans rely on our forgetfulness or oblivion in order for their designs to succeed, then perhaps it stands to reason that the corresponding antidote would be that which removes the oblivion: high-resolution approaches to truth such as that implied by the notion of aletheia, and aletheia’s helper “mnemosyne” or “memory” — that is, the remembrance of that truth.

A series of gold inscriptions found buried with the dead across the ancient Greek world, and believed to belong to a countercultural religious sect, contained instructions for the soul of the initiate navigating the underworld, so that they might avoid the spring of Lethe and drink instead from the waters of Mnemosyne. A version of these fragments reads:⁴

“You will find in the halls of Hades a spring on the right,

and standing by it, a glowing white cypress tree;

there the descending souls of the dead refresh themselves.

Do not approach this spring at all.

Further along you will find, from a lake of Memory [Mnemosyne],

refreshing water flowing forth. But guardians are nearby. And they will ask you, with sharp minds,

why you are seeking in the shadowy gloom of Hades.

To them you should relate very well the whole truth [a form of aletheia combined with a form of katalegein];

Say: I am the child of Earth and starry Heaven;

Starry is my name. I am parched with thirst; but give me to drink from the spring of Memory.

And then they will speak to the underworld ruler,

and then they will give you to drink from the lake of Memory,

and you too, having drunk, will go along the sacred road that the other famed initiates and bacchics travel.”

It is easy, indeed, to accept the first, most salient, or most convenient solution we are offered to our problems, particularly when we are desperate for nourishment or salvation. But often, this turns out to be a trap. The soul of the hero or initiate is wary of such traps, however, and he finds his way through the deceptions of the underworld to the true spring by successfully speaking aletheia – that is, by retaining enough of a sense of rooted awareness to chart his precise position and trajectory on the metaphorical map of reality, and his relationship to the vast and complex world beyond himself.

Perhaps, by collectively holding ourselves to a higher standard of truth — one that keeps us mindful of uncertainty, well-rounded precision and nuance — we can do the same; and perhaps we might rescue our Lady Aletheia, at last, from the dark depths of the well where she lies now, yearning for the sunlight.

A Muse of Mount Helicon beating on a frame drum in an attempt to awaken Aletheia — pictured as a pearl of wisdom — where she sleeps, at a depth of 12,500 feet below sea level, in the ruins of the Grand Staircase of the RMS Titanic (representing another tragedy of man’s hubris).

Notes

1. Translated from German using ChatGPT.

2. Among scholars of classical Greek literature, there is a longstanding discussion over exactly what the word “aletheia” meant to the ancient Greeks. There is consensus that it is the absence of “lethe,” but the nuances are subject to interpretation. I have attempted to stitch together a composite picture, using the available analyses, that is both historically credible as well as philosophically fruitful and interesting.

The interpretations used here are drawn primarily from Homer, Hesiod, and the anonymous Homeric Hymns, the earliest known works of Greek literature. Over time, we see the use of “aletheia” become more broad and generalized, until these philosophical nuances seem to have been lost.

Thomas Cole writes in Archaic Truth:

“Hiddenness (or failure to be remembered) and its opposite are conditions which should attach to things as well as to the content of statements. Yet it is almost exclusively to the latter that alêthês refers in its first two and a half centuries of attestation. A Greek may, from the very beginning, speak the truth (or ‘true things’), but it is not until much later that he is able to hear it (Aesch. Ag. 680), or see it (Pind. N. 7,25), or be truly good (Simonides 542,1 Page), or believe in true gods (Herodotus 2,174,2). And it is later still that alêtheia comes to refer to the external reality of which discourse and art are imitations.”

3. Alexander Mourelatos also recognizes a “triadic” division of the nature of aletheia, although he conceptualizes that division in a slightly different way. The end result, however, is still to orient our focus toward the limitations on our certainty which arise at each successive node of the communication process:

“In Homer ἀλήθεια involves three terms: A, the facts; B, the informer; C, the interested party. The polar opposite of ἀλήθεια in Homer is any distortion which develops in the transmission from A to C.”

4. Actually, this is a composite formed from two fragments: “Orphic” gold tablet fragment B2 Pharsalos, 4th century BCE (42 x 16 mm) OF 477 and fragment B10 Hipponion, 5th century BCE, (56 x 32 mm) OF 474 (taken from The ‘Orphic’ Gold Tablets and Greek Religion: Further Along the Path by Radcliffe G. Edmonds).

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: Brownstone Institute Read the original article here: https://brownstone.org/