What would happen if a person consumed a spoiled egg-salad sandwich from an intergalactic gas station bathroom vending machine? In trying to answer this age-old question, “Parasite Lost,” a 2001 episode from the first run of the perennially resurrected Matt Groening cartoon, Futurama, ingeniously manages to convey a host of intriguing concepts from parasitology, microbiology, ecology, and probably several other scientific ologies far better than practically any textbook or TED Talk ever could.

In the episode, the primary protagonist, Phillip J. Fry, a rather dim Gen-X slacker, reawakened in the year 3000 after accidentally freezing himself in a cryogenic chamber on New Year’s Eve 1999 (or after being deliberately frozen by a time-traveling alien to later save the world depending on how far you made it in the series) develops superpowers after ingesting the aforementioned bit of intergalactic cuisine.

Naturally, the reason for the development of his powers is that the rotting sandwich contained an advanced species of parasitic worm that took it upon themselves to make some improvements to their new home upon arrival. From the perspective of the worms, improving Fry’s body was an infrastructure project. As a result, he ends up with super strength, rapid wound healing, and enhanced cognitive abilities.

When Fry eventually evicts the worms upon becoming worried that his long-time on-again-off-again love interest is falling for him, but only because of what the worms are turning him into, he consequently loses his newfound superpowers and finds himself struggling to make himself worthy once more of his love interest’s affection without the aid of performance-enhancing parasites.

Now, strictly speaking, the episode does get some things wrong. Realistically, if you eat a spoiled egg-salad sandwich from an intergalactic gas station bathroom vending machine, you’re probably more likely to develop a bad case of intergalactic diarrhea than the ability to survive a steel pipe through the chest or to masterfully play the Holophonor. Also, parasitic worms tend to lack arms. They don’t fight with swords. Their ruler generally doesn’t wear a crown. And, to the best of my knowledge, there has never been a documented case of parasitic worms erecting a statue of their host within their host with a sign reading “THE KNOWN UNIVERSE.”

But, the episode does manage to depict “The Known Universe” from the perspective of an organism that spends its life inside of another organism quite brilliantly. To a worm living inside you, you are the environment. For one of these organisms, altering some aspect of your physiology is like some beavers altering the course of a stream.

The fact that in Fry’s case, the worms provided some benefit, even if he came to think of it as a monkey-paw kind of curse, is what makes the episode more memorable than if he simply became sick. Furthermore, whether intentional or not, the episode illustrates a cornucopia rich with scientific ideas most people in 2001 would not have gotten in their high school or non-major biology class (e.g. the hygiene hypothesis, probiotics, therapeutic helminths, Richard Dawkins’ extended phenotype, microbial ecology, the microbiome) while prompting viewers to think about their place in the universe from the point of view of something that thinks of them as the universe.

Whether all this was in the collective mind of the writers back in the early 2000s or how much they knew about some of these concepts when writing the episode is unclear. Some of the ideas had been around for quite some time. Others really even weren’t being discussed by scientists in relevant fields en masse for practically another decade. Maybe their presence was a happy accident. Then again, Futurama, like Matt Groening’s other show, The Simpsons, has been known for having its share of STEM nerds in the writers’ room.

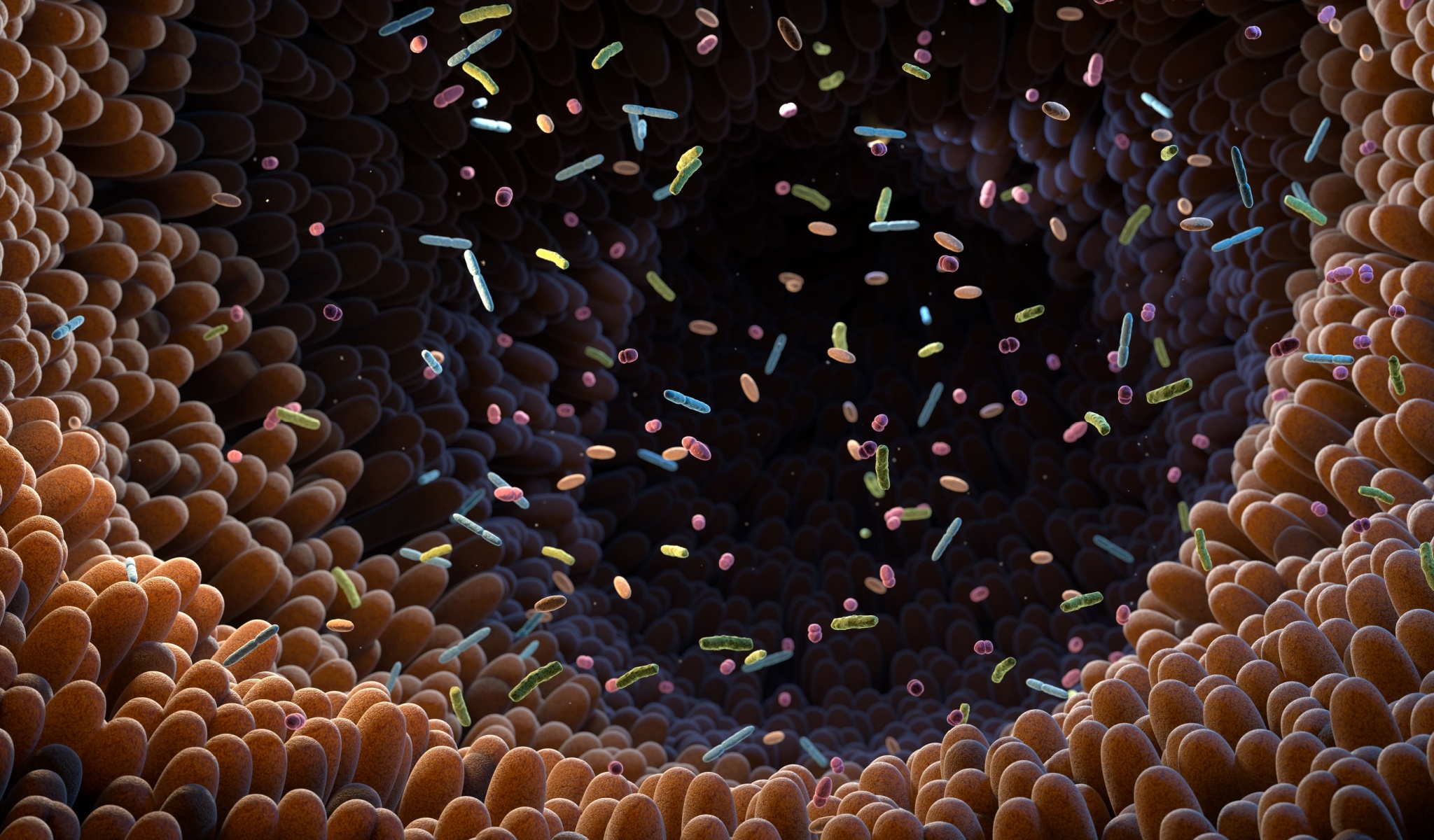

In either case though, today it is well understood that different parts of an organism’s body can be thought of as complex environments and ecosystems teeming with life. Changes to these environments can impact the composition of these communities. Alterations to these communities can damage or improve these environments. Sometimes this hurts you. Sometimes it can help.

Taking the example of the human gastrointestinal tract and the gut microbiome, the microbes that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract, generally, are prevented from direct interaction with their host by a mucus layer produced by specialized cells called goblet cells. Additionally, there are many different types of immune cells that help keep your microbes in check and a thin layer of epithelial cells that overlay a layer of connective tissue called the lamina propria, rich with more immune cells. In a healthy gut, the mucus layer, along with various pores and transporters, helps regulate what makes it past these barriers, thus allowing water and nutrients from food to be absorbed while preventing or at least minimizing the passage of live bacteria and parts of bacterial cells, as well as any number of possible antigens and microbial toxins that may be present.

Yet, when the gastrointestinal tract’s mucus layer is degraded or its epithelial tissue is damaged, direct contact between a person’s gut and microbiome becomes more likely, as does the movement of things like live bacteria, parts of bacterial cells, and microbial toxins across the intestinal epithelium and perhaps into your circulatory or lymphatic system. This, in turn, can result in increased inflammation in the gut and low-grade systemic inflammation known as endotoxemia, both of which likely contribute to the development or exacerbation of conditions like diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, cardiovascular disease, and various autoimmune diseases.

The exact causes of such degradation and damage are numerous and complex, with some such as aging and certain genetic predispositions likely being beyond one’s control. Others, however, are likely linked inextricably to modern life in the West.

For decades researchers have noted that inhabitants of Western societies are plagued by maladies largely considered rare or unheard of in earlier days or non-Western societies, especially those maintaining more traditional hunter-gatherer ways of life. It also has been noted that when those from non-Western societies move to Western countries, or their own homelands become Westernized, cases of various metabolic, gastrointestinal, and autoimmune conditions tend to go up, especially if they are children at the time the change occurs.

One likely source for this is what we now eat in Western societies. The Western diet, as it has been dubbed, is generally characterized as being high in energy, sugar, salt, and animal fats and proteins, while low in fiber from fruits and vegetables. In the Western diet, there’s also a larger quantity of dairy, cereal grains, refined sugars and oils, salt, and alcohol than what may have been normal 200-10,000 years ago, offering evolution little time to help us adjust. Additionally, there are numerous modern inventions like emulsifiers, preservatives, and countless lab-concocted flavors and colors.

Broadly speaking, this diet is believed to decrease microbial diversity in the gut, promote gut colonization by some rather nasty pathogens, degrade the mucus layer of the gut, increase intestinal permeability, and spur the proliferation of inflammatory immune cells. More specifically, meat contains the precursors to several pro-inflammatory molecules. Saturated fatty acids promote the growth of some sulfate-producing bacteria associated with inflammation and damage to intestinal tissues.

Anti-inflammatory metabolites produced by colon bacteria from fruit and vegetable fiber are seriously reduced in people not consuming a sufficient amount of fruits and vegetables, as are the bacteria that produce these metabolites – unless of course they get desperate and start “eating” your intestinal mucus. Many of those newly invented additives in our food likely either directly stimulate inflammatory processes or help further erode your intestinal lining to make it easier for other things to stimulate those processes.

Although exhaustively untangling every relationship alluded to above would be well beyond the scope of this essay, based on what we know about human physiology and the gut microbiome, it is probably safe to say that none of this is good. It is also probably safe to say that all this likely leads to something of a vicious cycle, increasing your likelihood of developing one or more Western maladies.

As for what meaningfully can be done on a personal or societal level, this is a bit trickier. Some of the lab-invented concoctions that, for all practical purposes, are probably poisoning us, could be studied better and perhaps outright banned by the government if they are found to be as bad for our health as they appear to be. Then again, calling for more government regulation over what we are allowed to eat seems like the kind of Faustian bargain that will just empower a breed of nanny-statist bureaucrats all too eager to micromanage everything we eat, yielding policy after policy to regulate our diet the way the climate crowd is regulating light bulbs, large home appliances, cars, and pretty much every other machine perfected in the mid-to-late 20th century into something equally unusable and unenjoyable.

Moreover, it does not seem unthinkable that the large companies producing the worst lab-invented concoctions in our food would be able to skirt regulation by ever so slightly altering the chemicals in their products the way the developers of designer drugs once did while mom-and-pop bakeries get raided by law enforcement for continuing to use the outdated version of an artificial sweetener they happened to still have in the back.

Alternatively, if one is going to make a bargain with a parasite, why not go for one far less vile? like a respectable species of intestinal worm? Yes, parasitic worms have gotten some bad press recently for eating part of Bobby Kennedy, Jr.’s brain but not all of them are that bad. Some actually are a little closer to those that infected Phillip J. Fry just under a thousand years into the future. Realistically, they won’t give you superpowers, but they might be able to restore some order to the environment within you that has fallen into a state of disarray.

Strictly speaking, not having a belly full of worms is a modern, Western luxury. For most of our existence, they were our near-constant companions. In many parts of the world, they still are. But thanks to modern sanitation practices, these parasites have largely been lost in the West. Consequently, there are questions regarding whether their absence plays a role in the West’s epidemic of gastrointestinal, metabolic, and autoimmune diseases.

Correlative data does show a pattern. Autoimmune and other inflammatory disorders tend to be higher in places where parasitic worm (or helminth) infections are lower or nonexistent. The primary reason hypothesized is that humans and helminths co-evolved over the course of our existence, with helminths developing the ability to attenuate some of our immune responses as a matter of self-preservation. If a person’s immune system overreacted to something, the worms had an emergency switch to tune it down. When we lost our worms, we lost our emergency switch. As some ecologists talk about reintroducing the bison to the prairies of the Midwest in which they once thrived, some researchers have suggested we reintroduce the noble helminth to our guts. Perhaps returning these majestic creatures to their native habitat would also help us adjust to our modern diet.

Then again, our relationship with helminths was never perfect. Although harboring a limited number in your gut might provide some benefit, the extent of which is still being assessed, having too many can lead to bowel obstruction or anemia. Plus, although helminths generally have no reason to set up camp in your brain, spinal cord, or one of your eyes, sometimes a single helminth with an adventurous spirit or perhaps a bad sense of direction can make it to one of those locales and do some pretty serious damage.

Alternatively, probiotics (live bacteria with putative benefits to a host) have received quite a bit of attention for at least a couple of decades but come with their own problems. Although most people would probably think of them as more acceptable than worms, it’s not clear how much benefit you actually get by just flooding your gut with yogurt or well-marketed probiotic pills. The research is mixed.

Some studies show health benefits. Others don’t. Plus, temporary administration generally doesn’t lead to long-term colonization. And, whether in yogurt or capsule form, most probiotics tend only to contain different varieties of Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria, and Streptococcus thermophilus, which, despite probably providing some benefits, tend to be used in probiotics simply because they are among the easiest “good” bacteria to grow, store, and get to the GI tract alive, while a multitude of others that may be equally if not more important go ignored (or at least remain difficult to administer outside of an experimental setting).

To have any impact on that multitude of everything else that can’t be packaged as easily, ideally long-term, one once more likely needs to think about diet. One alternative to the Western diet that gets a lot of attention, and may be able to allay or reverse some of the damage to our guts and the microbial communities that call us home, is the Mediterranean diet. Characterized as being high in fruits, vegetables, legumes, and olive oil accompanied by limited amounts of fish and red wine, the Mediterranean diet is believed to decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, at least in part by spurring changes in the composition of the gut microbiome. For example, the increased fiber, legumes, nuts, and phytochemicals found in this diet are thought to promote the growth of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria while suppressing the proliferation of pathogens like Clostridium perfringens.

That said, even if one isn’t ready to make the leap and embrace a Mediterranean diet or comparable alternative (as a matter of full disclosure the first draft of this article was written over the course of multiple visits to a coffee shop and fueled by copious amounts of caffeine and pastries containing many of the modern inventions I’ve advised against) a little common sense and some willpower is probably a good start to remediating the ecological and thus physiological damage caused by what you’ve been eating.

The right ratio of plants to animal protein might not be an exact scientific equation you can easily figure out as you decide what to eat on any given day, but consuming bacon and eggs for breakfast, a cold cut sandwich for lunch, and a piece of meat accompanied by a baked potato saturated with a butter alternative is probably not going to bring you close to whatever that golden ratio might be.

Likewise, eating like a fat influencer (sorry, I mean body positivity activist) on TikTok is probably not a good idea either. Most of the foods that get you to the Pac-Man frog phenotype so many of them seem to have embraced are filled with the kinds of modern chemicals that are wreaking havoc on your gut environment (plus there’s the not unrelated obesity issue).

Hence, simply put, less meat, more fruits and vegetables, and much less of all the things on the food label you need a master’s in chemistry to even pronounce, won’t work miracles but is probably a solid first step to a healthier gut. And it’s probably one that would be appreciated by many of the friendly bacteria that think of you as the known universe.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: Brownstone Institute Read the original article here: https://brownstone.org/