In 1967, a cloud of idealistic young Americans descended on San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district for the Summer of Love. At the epicentre of the hippy counterculture, they rejected materialism, conformity and war, instead embracing art, spirituality, community and psychedelic drugs.

From this moment emerged a potent modern revolution in evangelical Christianity, led by one of the Summer of Love’s most compelling refugees. Lonnie Frisbee was a gay, Rasputin-like mystic who believed in the transformative power of LSD; he would “party on Saturday night and preach on Sunday morning”. His story is counter to the Hollywood narrative of that summer in San Francisco — but, in its darkness, it is far more in line with reality.

The streets of Haight-Ashbury were certainly filled by girls with daisies in their hair and guys with outsized flares seeking to “turn on, tune in, drop out,” in the words of Timothy Leary, godfather of the hippy movement. But soon enough, the district’s new residents realised that “turning on” to free love gave rise to a widespread culture of rape; “tuning in” saw a spontaneous movement transform into a commercialised spectacle; and “dropping out” found free-spirited flower children sleeping on park benches. As one pamphlet put it, at the time: “Minds & bodies are being maimed as we watch, a scale model of Vietnam.”

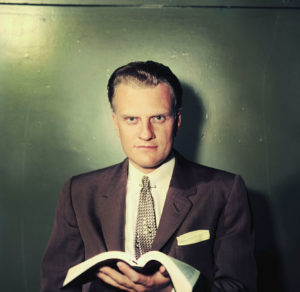

Now, a new film has arrived to both illuminate and further obscure the cultural effect of that summer. Jesus Revolution, starring Kelsey Grammer, portrays one of the most important evolutions in modern Christian history: the “Jesus People” movement (also known as the Jesus Movement or Jesus Freaks). Grammer plays Chuck Smith, the buttoned-up pastor of Calvary Chapel, a struggling Pentecostal church in California’s Orange County, who had a chance meeting with the teenage Lonnie Frisbee. A disaffected hippy, Frisbee was hitchhiking down the California coast after spending the Summer of Love tripping on acid and reading the Bible, having converted to Christianity in a San Francisco commune.

Based on the memoir of Greg Laurie — who worshipped under both Frisbee and Smith in the Seventies, and in turn became a prominent evangelical preacher — Jesus Revolution offers Frisbee a far more prominent role in contemporary Christian history than he is usually given. Yet as with other representations of Frisbee’s life, the film also writes him out at a convenient moment, long before his gruesome, lonely death from AIDS in 1993. His sexuality is ignored.

Frisbee’s legacy is profound, but constantly overlooked — as is the wider movement. Jesus People probably couldn’t have happened at any other time or place than the beaches of Orange County, south of Los Angeles. It was a hotbed of internal migration in the post-war years, as families from the Midwest escaped the farms and factories hollowed out by the Depression. The region’s burgeoning defence industry offered entry into the middle class. Carrying little more than their hopes, faith and conservative values, these new arrivals helped transform the region into the seat of the modern evangelical movement.

These hard-working Americans seem to be at odds with the 19-year-old Frisbee, who attracted young people to Calvary Chapel with devotional music that could have been played on the stages of the future Woodstock. But Smith, according to the film, saw something in him that could bring young people like his daughter back into the fold. They found a new way of doing church, but their union was building on ideas that had started in Pentecostal churches in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, where renegades insisted — in something that was hotly resisted by church leaders of the day — that instead of waiting for the blessings of the Holy Spirit to work their miracles, believers could experience these wonders “on demand”.

Here was a Christianity that could find not only historical justification, but a home in the spirit of the Sixties and its growing consumer culture. Calvary Chapel was a place to feel good as well as feel God — an evangelical version of the Summer of Love. Frisbee’s magnetic appeal was the spark able to bring the masses to the movement. Described by some as a figure akin to the biblical Samson, Frisbee was uniquely blessed with the ability to speak to the moment, but ultimately brought low by temptation. He was, after all, still preaching to a congregation who were evangelical Christians, in both temperament and values; most of them weren’t hippies. His renegade style and personal life were only going to cut it for so long, and he was eventually cast out — of the movement, and the film.

Jesus Revolution moves onto Greg Laurie’s story here, but in real life a far more interesting character stepped up to fill Frisbee’s shoes. John Wimber, a fellow hippy who was in a Sixties rock’n’roll band called the Paramours — which went on to become the Righteous Brothers, of whom he was the manager — was at that time described as a “beer-guzzling, drug-abusing pop musician, who was converted at the age of 29 while chain-smoking his way through a Quaker-led Bible study”.

Wimber became a central figure at Vineyard, a church affiliated with Calvary Chapel, where he helped mould the energy of Frisbee and the sensibility of Smith into a more far-reaching and coherent Christian revival movement. Today, they’re known as the Charismatic and Neocharismatic movements, or the second and third waves of Pentecostal Christianity, but labels aren’t that important. What matters is the way in which they spread like wildfire through churches in California, and eventually the world.

Wimber’s “power evangelism” — a term first associated with Frisbee, but now largely credited to his heir — is best described by the former rock’n’roll pioneer’s own formulation of doin’ the stuff. “When I worked for the devil, he let me do his stuff,” Wimber said. “But when I came to work for Jesus, they didn’t want to let me do His stuff. To tell you the truth, I joined up to do the stuff!” The stuff is the direct experience of the signs, wonders and miracles of the Holy Spirit promised in the Bible, such as faith healing, prophecy and speaking in tongues. In the old days, you had to go to your preacher for that. The genius of the former hippies was to change that, satisfying the cultural desire to have direct experience with the stuff. As anthropologist T.M. Luhrmann put it: “If God is present in a literal sense, you no longer need to turn to intermediaries to learn what his wishes are. You can ask him yourself.”

This kind of Christianity spoke to cultural icons of the hippy era, up to and including Bob Dylan, who went to Wimber’s Vineyard bible school in 1978, after the singer felt Jesus as a “physical thing” and began to tremble in his hotel room. “The glory of the Lord knocked me down and picked me up,” he later said. But Dylan was a late adopter to what was by then Wimber’s movement, which was drifting a long way from Frisbee’s ideals. The Jesus People movement, which was now Charismatic Christianity, was beginning to look more McDonald’s than McCartney. The direct descendants of this movement can be found in churches such as Hillsong, the Australian megachurch that has recently seen an almighty fall from grace. Earlier this month, it was accused of failing to report $80 million in profit, while its founder, Brian Houston, was alleged to have spent $150,000 on a luxury family holiday in Cancun, as well as many more thousands on “the kind of shopping that would embarrass a Kardashian”. This fully corporatised church would be unrecognisable to even the most disillusioned Haight-Ashbury refugees.

Frisbee has been written out of not only the Jesus Revolution film, but Wimber’s six published books. A gay party animal, even in 2023, is an unappealing saint for the average believer. In Wimber’s version of the revolution, the person who transformed evangelical Christianity with his New Age power evangelism is only briefly mentioned as “the young man”.

Nevertheless, Frisbee and his Jesus People’s profound effect continues to be felt today. At a time when church attendance is in decline in the United States, those more broadly described as Charismatic attend the most. Theologian Dale M. Coulter recently wrote that the two major features of the Charismatic spiritual tradition are “narrative and journey” — hinting at the way evangelical Christianity has found new relevance since the Sixties. They modernised salvation, created personal relationships (He died for me) and turned the Lord into a mate (Jesus, minus the Christ). Waiting around to be saved by God was no longer a thing, because hippy Jesus became a consumer choice — a massive festival, where you can enter the tent for a guy who looks and sounds just like you. Today, the heirs to Frisbee, Smith and Wimber’s movement are largely doin’ the stuff through a one-click checkout; to survive the capitalist age, evangelism has commercialised.

But there are hints of a spiritual revival. The recent Asbury Revival, which attracted tens of thousands of GenZs to a mass pray-in at Kentucky university, proved that there’s a new generation who are still attracted to this Christian message. Young people are regularly attending services, from Lagos to London and New York City, and they’re joined by modern cultural icons, including Premier League players, rappers, and various Kardashian-Jenners. They hold church in commercial theatres, and attract devoted followers, among them TikTok influencers and hardcore conservatives. All are looking for something they can believe in, and a relationship with God that they can control. Most of these believers won’t even know Lonnie Frisbee’s name, but they certainly feel his legacy. And that is, quite simply, that you can be a Christian in a secular world. You can do the stuff and not have to go without. And as Jesus Revolution shows, a lot of the stuff involves telling a good story that doesn’t entirely reflect historical reality.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/