This is an initiative of the University of Leeds, in cooperation with Brownstone Institute, to clarify the evidence base on which history’s largest public health program is being built.

Public health serves a vital role in strengthening population resilience to threats to well-being and in responding to such threats when they occur. This requires a holistic approach that recognizes both the interconnection between humans and their environment, and the broad scope of “health” – internationally defined as spanning “physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”

Dealing with pandemics and other health emergencies is an important aspect of public health. Interventions must be weighed against potential direct and indirect benefits, the probability that an intervention can be realized, and the direct and indirect costs that will be accrued.

Such costs and benefits must include social and mental impacts, assessed within an ethical framework that respects human rights. Human populations are diverse in terms of risk, whilst priorities are influenced by cultural, religious, and social factors, as well as competing priorities arising from other diseases. This requires careful policy development and an implementation approach that responds to public need and is consistent with the will of the community.

The University of Leeds, through an initiative backed by Brownstone Institute, recognizes the need for publicly available evidence to support a measured approach to pandemic preparedness that is independent and methodologically robust. The REPPARE project will contribute to this, using a team of experienced researchers to examine and collate evidence, and develop assessments of current and proposed policies weighed against this evidence base. REPPARE’s findings will be open-access and all data and sources of data will be publicly available through a dedicated portal at the University of Leeds.

REPPARE’s primary intent is to facilitate rational and evidence-based approaches to pandemic and outbreak preparedness, enabling the health community, policy-makers, and the public to make informed assessments, with an aim to develop good policy. This is the essence of an ethical and effective public health approach.

The Current State of the Pandemic Preparedness Agenda

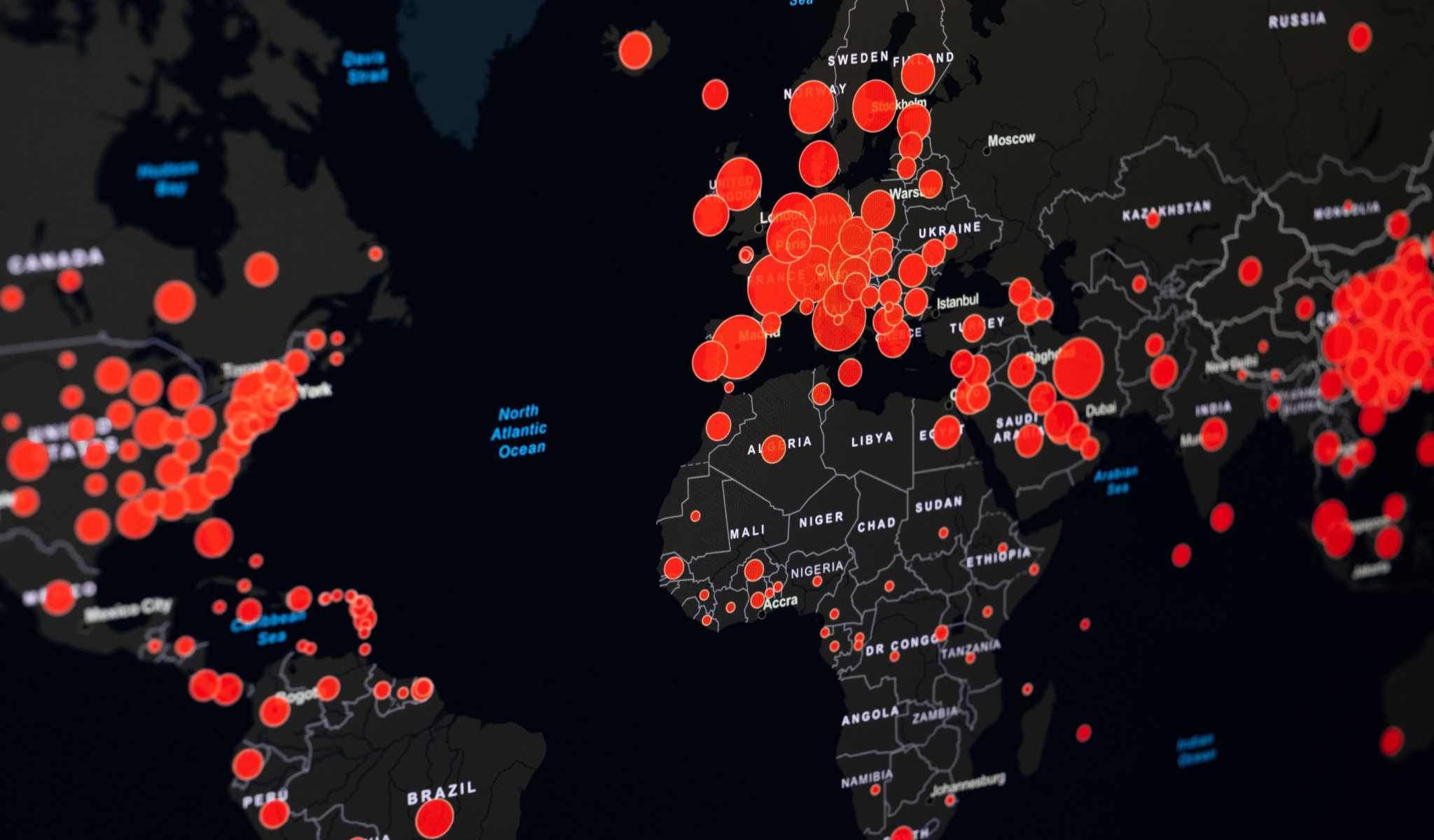

Pandemic preparedness, barely on the agenda a decade ago, now dominates global public health messaging and funding. Humanity is reminded, in white papers from the United Nations, the World Health Organization (WHO), and other organizations such as the G7 and G20, that rapid action and investment is essential to avert a probable existential threat to human and societal well-being. Using COVID-19 as an exemplar case, these documents often warn us of far worse to come.

If this is correct, then humanity had better take this seriously. If it is not, then the largest wealth shift and reform of health governance in centuries would constitute a policy and resource misdirection of stunning magnitude. The University of Leeds, with support of Brownstone Institute, is taking a rational and measured approach to assessing the evidence base and forward-looking implications of the emerging post-COVID-19 pandemic preparedness and response (PPR) agenda. Those working with good intent on all sides of this debate need thorough evidence that is publically available and open to scientific deliberation.

A Divergence in Public Health Thinking

The past two decades have witnessed the increasing divergence of two schools of thought within global public health. The Covid-19 pandemic and subsequent pandemic preparedness and response (PPR) agenda have brought these to a level of vitriol, dividing the public health community. Health is a basic human need, and fear of ill health is a powerful tool for changing human behavior. Ensuring the integrity of public health policy is therefore critical for a well-functioning society.

One school, formerly prominent in the era of evidence-based medicine and ‘horizontal’ health approaches, emphasized the sovereignty of communities and individuals as a primary or essential arbiter of policy. The risks and benefits of any intervention must be systematically defined and presented to populations with best available evidence, who then make rational decisions on health priorities within their own context.

This approach underpinned the Declaration of Alma Ata on primary care, the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, and continued into the 2019 WHO pandemic influenza recommendations, where potential responses to periodic pandemics was weighed against the potential harms of restrictions and behavior change and human rights, where the needs of local populations were held as a primary concern.

A second school of thought, increasingly expressed over the past two decades, holds that a pandemic and other health emergencies constitute urgent threats to human health requiring centrally coordinated or ‘vertical’ responses that require universal implementation and should thus override aspects of community self-determination.

Health emergencies, or the risks thereof, are held to be increasing in frequency and severity. Moreover, these risks threaten humanity collectively, requiring a collective response. As a result, uniform and mandated responses aimed to mitigate these threats override everyday health concerns, and public health adopts a role of establishing and even enforcing the response, rather than merely advising.

The vertical approach is now being expressed in several international agreements currently under development, particularly in proposed amendments to the International Health Regulations (IHR) and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Pandemic Accord (formally known as the Pandemic Treaty). Resources being allocated to this area are set to dwarf all other international health programs.

They are intended to build an international surveillance and response network coordinated by WHO and like organizations based predominantly in developed countries, at a time when major infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and malaria, WHO’s traditional focus, are worsening globally. With $31.5 billion being sought for PPR annually, roughly eight times the annual global annual spend on malaria, collateral impacts through resource diversion appear inevitable.

Covid-19 and the Rethink of Roles and Rights

In the aftermath of COVID-19, the basis for the shift in priority of global public health, that pandemics are of increasing risk and frequency, is widely repeated by institutions driving this change. This is said to be part of an unprecedented conflation of multiple threats, or a ‘poly-crisis,’ facing humanity, associated with a growing human population, changing climate, increasing travel, and changing interactions between humans and animals.

The proposed responses, including the potential for mass vaccination and restriction on human movement and healthcare access, carry their own risks. During the Covid-19 response, employment of these measures underwrote a major transfer of wealth from low to higher-income people, loss of education with knock-on effects on future poverty, and a significant rise in both infectious and non-communicable diseases.

Whilst such impacts are used to justify an earlier response, they present major risks both to population and societal health. While some will hold that no threat justifies restrictions on human rights and democratic norms, nearly all will agree that such measures are not justified if the extent of the threat is overestimated, and the risk of collateral harms are demonstrated to outweigh that of the pathogen.

Clearly, any such fundamental changes in the approach to public health, tried for the first time during Covid-19, requires a strong evidence base. Currently, this evidence base is poorly articulated or absent from documents supporting the international pandemic instruments under development.

We are therefore, as a global society, reversing decades of understanding on human rights, health prioritization, and health equity based on underdeveloped assumptions. This is happening at unprecedented speed, with a global public health workforce being built around a pandemic preparedness agenda that will be difficult to undo, and highly expensive to maintain. It also requires imposition of fundamental changes in the interaction between public and private interests that had once been at arm’s length.

What We All Should Know

If the evidence underlying the pandemic agenda is flawed or absent, then humanity is facing a different form of risk. We risk the reversal of health and social gains made through an unprecedented period of prosperity and prioritization of human rights across the world, and a return to a more colonialist structure of elite led ‘traveling models.’ Public health as a profession will have returned to its historical blight of assisting in the degradation of societies, rather than their enhancement.

Moreover, we risk diverting a large amount of scarce resources from known communicable and non-communicable health threats that have everyday impacts. It is crucial to public health and to humanity that the current pandemic agenda be evidence-based, proportionate, and tailored to the overall good.

We have a short time in which to bring transparency and evidentiary reflection to this field. Both public health science and commonsense demand this. Pandemics happen, as do a wide range of preventable and non-preventable threats to health. They have been part of human society through recorded history, and it is prudent to prepare for them in a way that is fit-for-purpose and proportional.

Yet, if we are going to alter the way we deal with them, and this reverses the norms of human dignity and self-expression that we have long defended, we had better know why. Such decisions must be based on science and consent, rather than assumption, fear, and compulsion.

Project overview

Post COVID-19, global health governance is rapidly being remodelled on a stated imperative to address a major and rapidly growing threat of health pandemics. Under this new approach, health prioritization is changing and new regulations are being introduced to protect humanity from this threat. These changes will have major economic, health, and societal consequences. It is therefore imperative that proposed changes are made based on solid and best available evidence, so that policies are rational and likely to deliver the best overall outcomes. Policy-makers, and the public, must have access to clear, objective information about pandemic risk, costs, and institutional arrangements to enable this to happen.

Overall Project Objectives:

Primary Objectives:

- Provide a solid evidence base for assessing the relative risks of pandemics, and the cost-benefits of proposed responses as they are emerging in the new global pandemic preparedness and response agenda.

- Develop evidence-based recommendations for a rational, human rights-based and centered approach to pandemic preparedness and response.

Secondary Objectives:

- Provide focused published responses to significant areas of concern as the PPR agenda evolves.

- Provide evidence-based information regarding the proposed PPR changes in a form accessible to the public and other organizations.

- Stimulate debate and inquiry in the global public health community concerning the current trajectory of this sector and alternatives to current prioritization models.

- Produce a series of visual policy/media briefs relating key takeaways from the research for easy consumption and use.

Scope of Work:

The REPPARE team will address four interlocking work-packages:

1. Identification and examination of the epidemiological evidence-base for current key arguments underpinning the pandemic preparedness and response (PPR) agenda.

· The degree to which pandemics are a growing threat?

· How does this compare with other health priorities in terms of health and economic burden?

2. Examination of the costing of the PPR agenda:

· Are current cost estimates of the PPR agenda appropriate and how do they weigh current costs against competing priorities?.

· What are the opportunity costs of the proposed diversion of resources to PPR?.

3. Identification of the major influencers and promoters of the current PPR agenda.

· Who and what are the greatest influences on the PPR governance and finance architecture, and how are these governance structures designed and operating?

· How are stakeholders, including affected populations, represented in priority-setting, and who is left out?

· Does the current architecture appropriately respond to identified risks/costs?

4. Is the current international approach appropriate to pandemic as well as broader global health needs, or are there better models that could serve the broad needs of humanity while proportionately addressing health threats?

REPPARE will examine and build the evidence base relevant to the pandemic agenda over two years, but continually make data and analysis available to the public. The aim is not to advocate for any current political or health position, but to provide a basis on which such debate can occur in a balanced and informed fashion.

Humanity needs clear, honest, and informed policies that reflect the aspirations of everyone, and recognizes the diversity and equality of all people. The REPPARE team at the University of Leeds, with the support of Brownstone Institute, aims to contribute positively to this process.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: Brownstone Institute Read the original article here: https://brownstone.org/