Policy Founded on Distorted Evidence

by Tom Jefferson at Brownstone Institute

How can decision-makers justify promoting the mammoth undertaking of annual influenza vaccination when the best-quality evidence base is nearly empty?

This was the first question we left you with in the previous post.

In 2008, we examined several policy documents written by influential organisations from WHO, the UK, the US, Germany, Australia, and Canada. The power brokers of influenza prevention created compelling policy arguments for vaccination. For example, the WHO estimated that “vaccination of the elderly reduced the risk of serious complications or death by 70-85%.” What they didn’t point out was that this estimate was based on single studies. In the US, reductions in cases, admissions, and mortality of grandma were central arguments for extending vaccination to healthy children aged 6-23 months.

Therefore, we asked simple questions like who wrote the policy documents, whether there was a methods chapter explaining how the bigwigs reached their conclusions, and whether they had done some quality assessment of the studies or the data.

We were persistent and looked inside some of these documents. All policy documents contained misquotes, selective citation of text or results, factual mistakes in reporting either estimates of effect or the authors’ conclusions, inconsistent logic, and contradictions.

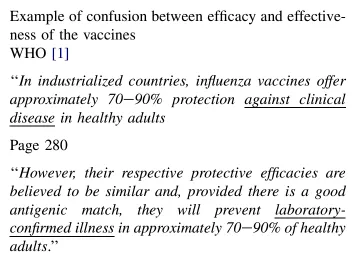

Examples included confusion between efficiency and effectiveness:

Clinical illness is influenza-like illness (ILI) or the F word Flu.

When you have laboratory confirmation of influenza, Flu or ILI become either influenza or Rhinovirus, parainfluenza or one of the scores of agent specific infections who give the same set of symptoms: fever, malaise, cough, aches and pains and so on.

Testing for ILI assesses the effectiveness of a vaccine. Testing for any specific agent assessed the efficacy of the vaccine. Got it? They are two different things: vague or very specific.

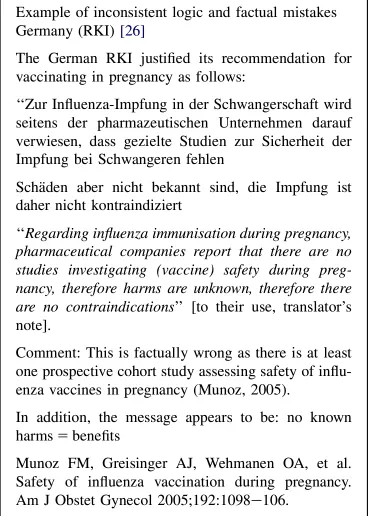

Inconsistent logic and factual mistakes in the recommendation for vaccination in pregnancy were seen with the German Robert Koch Institute.

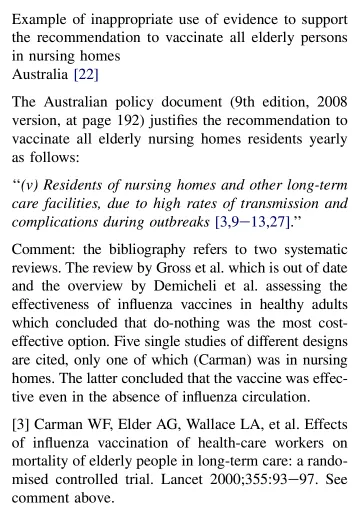

Examples also included inappropriate use of evidence to support recommendations.

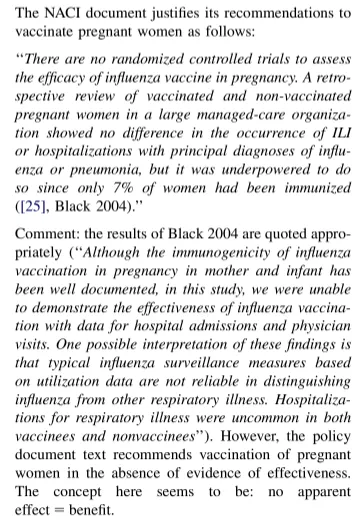

The National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI), Canada’s equivalent to the US CDC’s ACIP, used logic inversion to support their policy on pregnant women.

All of the documents showed extensive cherry-picking of the evidence. For example, the section on evidence of efficacy and effectiveness of the vaccines in children of the US ACIP document cites ten comparative studies and one noncomparative study out of a possible total of 78, and the reasons for the selection are unclear.

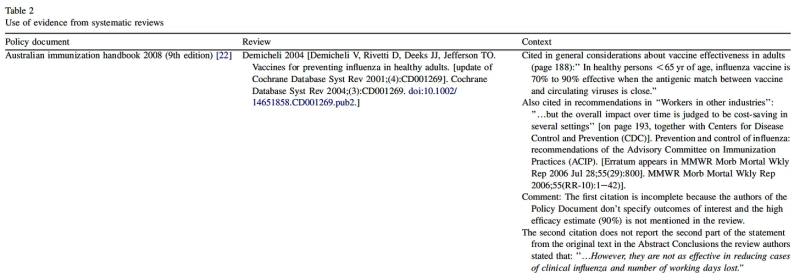

Beyond such selective use of the evidence, the Australian Public Health Body’s handbook also misquoted the 2004 version of our review in healthy adults:

So, the policy justifications were misleading, often cobbled together in a distorted fashion, and unreliable. There are scores of other examples from the era. But the message was clear: policymakers did not take scientific evidence seriously regarding policymaking. Emails from NIH and CDC, which we presented in the series’ second post, leave us little hope that anything has changed.

So the answer to the initial question of how decision-makers can justify promoting the mammoth undertaking of annual influenza vaccination is: by distorting and cherry-picking the evidence, if they ever cared for it.

In the next post, we will provide possible answers to why influenza vaccines have played a prominent role in the last two decades.

This post was written by an old geezer who’s been working on this for three decades and hopes that the content of posts like these will be his legacy.

Readings

Jefferson T. Influenza vaccination: policy versus evidence BMJ 2006; 333:912 doi:10.1136/bmj.38995.531701.80

Jefferson et al. Inactivated influenza vaccines: methods, policies, and politics. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009 Jul;62(7):677-86. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.07.001.

Republished from the authors’ Substack

Policy Founded on Distorted Evidence

by Tom Jefferson at Brownstone Institute – Daily Economics, Policy, Public Health, Society

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: Brownstone Institute Read the original article here: https://brownstone.org/