This general election could well break records: pollsters are predicting the lowest turnout in modern history. People feel politically homeless. That there’s no point in voting. That none of the politicians can change anything. In this respect, they have a point. And I share their apathetic outlook. All the parties are making election promises about outcomes which our state no longer has the capacity to deliver.

Britain is a country with moderate natural resources and moderate human capital. Where we have excelled is in the strength of our institutions. But the effective delivery of public services depends on the capability, motivation and organisation of public servants, and right now, that can’t consistently be counted on.

So what’s changed? I joined the Civil Service not long before the financial crash when, despite the relatively low salary, good roles attracted smart graduate talent because the work was interesting, often prestigious, and because people had a stake in the ultimate outcome — the successful functioning of the state.

That balance has shifted as years of pay restraint, combined with soaring living expenses, especially in London, have affected the calibre of staff. I know many excellent public servants who have left to triple their wages in the private sector. As a result, the country is getting fewer of our best people and state capability is suffering.

Troublingly, this isn’t just a question of splashing the cash. Even if there were budget to spare (which there won’t be), rebuilding and remotivating the workforce would be tricky. This is partly because the problem isn’t just a numbers’ one. It’s an attitude one. Even though the overall size and composition of the Civil Service today does not look that different from when I joined, some of the cultural norms — or “expected behaviours” — are unrecognisable. The most noticeable change is how comfortable younger cohorts have become with publicly expressing ideological views.

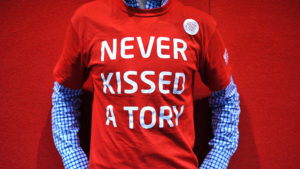

The politics of identity is by no means unique to the public sector, but it is uniquely problematic within it. To take one example, it is common to see pronouns attached to the email signatures of public servants. This does not concern me because of what it tells us about those public servants’ views of gender, but because it tells us something about their views. Public servants should be aware that exposing their institutions to accusations of ideological capture, by any type of political persuasion, is damaging.

Stephen Webb, a former Cabinet Office Director, points out that ambiguity around employers’ legal position makes the hierarchy hesitant to challenge any exhibitionist public-sector behaviours, such as displaying pronouns (sometimes incongruously overlapping with the wearing of Palestinian flags and other signalling devices). Or maybe the leadership feels it’s nothing more than passive social compliance and, therefore, not worth the fight. But the effect should not be dismissed. While it’s hard to imagine this kind of signalling leading to any of the outcomes proponents want to see, normalising this sort of ideological signalling has given licence to a growth in cause based, non-work activities in the workplace, which draws focus from core business. Inevitably it also affects productivity.

Such behaviour also blurs the distinction between passive exhibitionism and more overt acts of ideological capture. This could be seen when some civil servants in the Department for Business and Trade decided that, of all the countries to whom we export military equipment, they should threaten to refuse to process export licences to Israel. There is a balance to be struck between engaging sincerely with employees to get the best out of them, and pandering to the latest TikTok cause and its pseudo intellectual underpinnings.

And while the majority of public servants are passionate and professional, their jobs become increasingly difficult when the behaviour of their colleagues degrades their institution’s legitimacy. The Met Police, for example, were already struggling to defend themselves against accusations of permitting antisemitic and intimidating behaviour during the Palestine marches; something which has been made all the harder now one of their most senior advisors has been shown chanting “from the river to the sea”. Either these public servants do not understand that the role of public service is to serve the whole public, or they believe that ideological actions are more worthwhile than their jobs’ substance.

Or perhaps there is another motivating factor. Professor Daniel Kahneman, the father of behavioural science, argued that there is a difference between the “experiencing self” and the “remembering self” (that is how the process of retrieving memories is prone to bias, meaning the impression we have of our past experiences can be different from how they really happened). Since, for many, the experience of real life now comes second to the way life can be presented online, I would argue that we are witnessing the emergence of a third “self” — the “representing self” — who experiences life in anticipation of how the experience can be represented on social media.

The decisions people make have long been influenced by what they think those decisions say about them, but social media has magnified this human frailty to such an extent it has changed the way consumer markets function: people participate in activities, choose their holidays and even adjust their worldview very conscious of how this will make them appear to their chosen identity grouping. Studies have shown a link between narcissistic traits and modern Western activism and — sadly — professionalism is no longer a barrier to this type of vanity: it motivates the choices some make in the workplace (as anyone who has had the misfortune to use LinkedIn will know). This, though, should not be the case in public service. If ideological distractions are permitted, it allows employees to show they feel more connected to ideology-based identity groups than to the communities and national community they are employed to serve.

Shifting behaviours and organisational culture is hard, though, particularly when the barriers to sacking employees is high. But the stakes for the country are even higher. We have many exceptional public servants, who feel increasingly let down by the overall effectiveness of their institutions and we risk losing them to better paying work. So we need leaders to reclaim responsibility for institutional culture from HR departments and will lead by example. Who will promote the talented and be empowered to sack those who are failing. Our public institutions have been allowed to crumble and if an incoming government fails to retain and reward those who can rebuild the legitimacy of these services, those electoral promises won’t be worth the paper they were written on.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/