In every culture, in every era, you will find the archetype of the cantankerous old man. He’s ubiquitous in cinema — the aged, scowling hero of Gran Torino; the feuding codgers of Grumpy Old Men; the dementia-stricken patriarch of The Father — but no less so in real life, where you can find him parked in an easy chair on the shady side of the porch, yelling at the neighbourhood kids to get off his lawn. He can be a comic figure or a tragic one, an object of respect or ridicule, but you ignore him at your peril. The next American president, after all, will be a cantankerous old man. We just have to decide if we want the one with the spray tan and the multiple felony indictments, or the one who recently confused the current French president with the one who died in 1996.

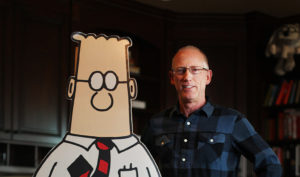

Some old men lose their edge as they age, while others develop a sharper one. Otto Penzler, the white-haired proprietor of the storied Mysterious Bookshop in New York City, would seem to be the latter. Now 81, Penzler is a polarising figure within the mystery writing community, the kind of person whose name elicits either a grin or a wince. In addition to building from scratch the biggest mystery bookshop in the world, he has edited dozens of mystery novels and anthologies and overseen multiple publishing imprints. At the height of his power, a good word from Penzler could make a writer’s career.

But his good words, his critics note, were reserved largely for white, male, heterosexual writers — and Penzler has a reputation for being less than reverent about the sacred cows of his more progressive peers. In 1991, he publicly criticised the women’s mystery writer’s group Sisters in Crime in an interview with the Chicago Tribune: “It’s a negative, flawed concept. It’s an organization that espouses non-sexism but is sexist.” In 2005, he described cosy mysteries as “not serious literature”, adding: “Men take [writing] more seriously as art.” More recently, he excoriated the Mystery Writers of America after the organisation, under pressure, rescinded its plans to honour mystery novelist and former prosecutor Linda Fairstein with a “Grand Master” award for literary achievement. (This was part of a broader campaign to cancel Fairstein over her role in prosecuting the Central Park Five, spurred by a Netflix series that portrayed her as the case’s chief villain; a defamation lawsuit brought by Fairstein against the series’ creators is currently making its way through the courts.)

Among those who dislike him, these incidents are seen as damning evidence in favour of Penzler’s defenestration. A recent X thread, prompted by his upcoming appearance at a mystery event called Bouchercon, bemoans his continued influence despite what the author describes as his “terrible opinions and inexcusable behavior” — although the behaviour in question, as I discovered in the course of reporting this piece, is more a matter of rumour than record. For those who remember the MeToo-era debacle of the Shitty Media Men list, it’s character assassination via whisper network: people will tell you that there are stories, but plead ignorance when asked to relate one. Penzler’s status as a Bad Man is entirely vibes-based. A snub here, a brusque comment there. Once, perhaps, there was a confrontation with a female critic who had panned a book written by one of Penzler’s friends, after she showed up uninvited to a party at his bookstore.

Penzler told me he doesn’t remember this incident, but admits that it’s in the realm of possibility. “Did I possibly call her a bitch, yes. Because she was,” he says, mildly — and if a comment like this makes you leap up in outrage, you are almost certainly not a person who would enjoy Penzler’s company. He’s friendly but blunt, impatient with foolishness, and — as he is the first to note — his personality doesn’t always play well in a world where people increasingly expect a soft touch.

When I first stumbled across that X thread, it initially struck me as no different from a hundred other minor publishing squabbles: the tiniest of tempests in the teensiest of teapots. But look through the lens of the zeitgeist, and there’s something intriguing here: an evolving and increasingly fraught relationship between the archetypal codger and a culture that no longer reveres him. We used to extend some grace to society’s granddads, acknowledging the possibility that a person old enough to have watched the moon landing live on TV might reasonably, if not wisely, see things differently from the strident 25-year-olds among us. But that grace has been replaced by a conviction that such opinions aren’t just embarrassing in an “old man yells at cloud” sort of way, but intolerable, harmful, toxic — and that a person who holds them needs to either get with the times, or be ostracised from polite society.

Mystery writing, like the rest of publishing, has undergone a reckoning in recent years — and what the diversity activists want is nothing less than a metaphorical asteroid hit, an extinction-level event that clears out the pale-male-stale old guard, and ushers in a colourful new world order. There’s just one problem: metaphorical asteroids, unlike their physical analogue, don’t actually kill the dinosaurs. And while it’s one thing to campaign for the ouster of dead white men from their various places of honour in the sciences, or the arts, or atop the lists of history’s greatest works of literature, it’s quite another to be confronted with live white men — men who’ve worked hard all their lives to get where they are, who do not agree that they have outlived both their relevance and respectability, and who are not about to slink off into obscurity just because the passage of time and the sensibilities of a new generation have rendered both their identities and opinions unpopular.

This all-encompassing presentism, in which every person must be judged by his worse offences against the pieties of the Current Thing, has found an even easier target than our oldest living citizens: those who are recently dead. It’s a phenomenon that makes for some interesting reads in the newspaper’s obituary section. “Herman Cain, a former Republican presidential candidate and supporter of President Donald Trump who pointedly refused to wear a mask during the coronavirus pandemic, has died after contracting COVID-19,” reported Reuters in 2020, while a New York Times obituary for former Interior Secretary James Watt informs readers that he “insulted Black people, women, Jews and disabled people”, before it describes his life or contribution to politics. As the writer Oliver Traldi quipped, “before you read about this man’s life, let’s precisely calibrate your sense of to what extent he was on the right side of history as conceived by readers of this absolute rag in the current year”.

Meanwhile, some progressives have taken it as an article of faith that we cannot wait anymore for these living relics to exit the world’s stage; we have to just push them out of the way. This sentiment was palpable in the MeTooings of people like Garrison Keillor, Al Franken, Leon Wieseltier, and Frank Langella, as well as the ouster of older white men from positions of influence in media, the arts, and more during the Covid-era Awokening. Even if you didn’t necessarily think these guys had done much — or anything — wrong, there was a sense that perhaps they should just go away on principle, for the sake of the cause. Hadn’t they been in power long enough? Wasn’t it time for them to step aside, and give someone else a turn?

On this front, Otto Penzler makes for an interesting case study: in 2021, he was fired from the Best American Mystery anthology series he’d edited since 1997, and replaced by editor Steph Cha, a young Korean-American novelist with whom he had butted heads over the MWA’s treatment of Linda Fairstein. In most situations like this, the outgoing editor is expected to go quietly, perhaps releasing an unctuous statement about the importance of making way for a new, more diverse generation of writers. Penzler, on the other hand, immediately launched a competing anthology that sold so well it currently stands at #13 in its category on Amazon. “We buried them,” Penzler says — a statement which, though difficult to truly quantify, seems roughly accurate: the 2021 edition of The Best American Mystery and Suspense, the first in 24 years not edited by him, is ranked #1312.

You come at the curmudgeon, you best not miss.

Of course in a previous, and perhaps less ridiculous, era, this disagreement — Penzler’s opinion of cosy mysteries and the mystery community’s opinion of Penzler — would be chalked up to a matter of taste. There was a time when it was possible to merely dislike someone, for whatever reason, without claiming that your personal animus was actually rooted in a bigger, braver struggle against oppression and isms and phobias. There was also a time when inviting a man to speak at a conference in his chosen field was understood as a narrow acknowledgment of that man’s achievements and expertise, rather than an endorsement by the organisers of his every opinion. Perhaps most important, there was a time when reasonable people would have agreed that if you are still citing the less-than-articulate comment someone made to a newspaper 33 years ago as a top 10 reason to destroy his reputation, you are engaged not in the advancement of social justice but a bizarre personal vendetta.

But in this moment, in which every personal beef is blown up into a proxy war for the ideological soul of the nation — or, in this case, the mystery writing community — the grumpy old men among us are seen less as human beings than reactionary avatars, a blight on progress. The result is a remarkably aesthetic-driven notion of what the proper distribution of power would look like, as with Joe Biden’s 2022 vow to consider only black female candidates as replacements for retiring Supreme Court justice Stephen Breyer, or the FAA’s strange attempt to stack the deck in favour of everyone except older white men in its hiring processes. But it also explains the furore surrounding someone like Penzler — who, despite his alleged disdain for women, has published, collaborated with, and championed scores of them over the years. This isn’t about the man himself, but what he represents: the bad old days, and bad old ways, which publishing’s self-appointed new guard have found dismayingly difficult to uproot. To get him booted from the Bouchercon stage would signal a shift in the power dynamic. It would mean that the asteroid had hit at last.

To fail to do this, on the other hand, would signal that the identitarian spasm in publishing — and whatever little power and credibility it once conveyed — is already on the wane. For the vibes, they are a-shiftin’ — but the grumpy old man endures.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/