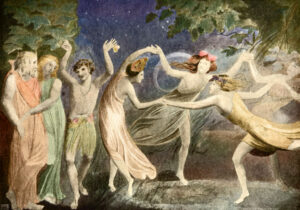

If history teaches us anything, it’s that you can’t be a warrior woman without some guy wondering what you’d look like going commando. According to Herodotus, after the Greeks defeated the Amazons, they loaded three ships with captives — only for the Amazon women to kill the ships’ crews and make landfall on coast of Scythia.

There they first fought with local Scythian men, only for those men to set up camp near them, creating an uneasy standoff. Herodotus recounts how the tension broke when a Scythian man met a lone Amazon woman near the camp, and sparks flew. After this, the two groups came together to form couples — though, even then, the Amazons refused to become Scythian village women, insisting their newfound husbands instead adopt their nomadic, pillaging ways.

The combustible cocktail of militarism and female sex appeal causes meltdowns to this day. Recently, news that 22-year-old US Air Force Second Lieutenant Madison Marsh had become the first active-duty soldier to be crowned Miss America caused instant media pandemonium: “She’s beauty, she’s grace, she’s bad to the bone,” said NewsNation.

Marsh is a serving servicewoman, accomplished martial artist, and Harvard graduate student as well as beauty queen: not so much “bad to the bone” as a genuinely impressive avatar of modern American respectability. Even so, does her victory really represent another step in the long march toward women being able to Have It All? In a very limited sense, perhaps. And if recent mutterings from the MoD about reintroducing conscription come with a side order of liberal feminism, perhaps the young women of Britain will soon be obliged to Have It All too, whether they want to or not.

No doubt, should this happen, some will claim it’s progress. But delving into the long history of women warriors reveals three interconnected truths. First, that female fighters are a long way from being a “stereotype-smashing” recent development. On the contrary, as far back as history reaches, there have been warrior women. And wherever such figures appear, we also find an overlap between violent militarism and sexual desire.

The upshot of this is that the role played in warfare by fighting women is rarely as straightforward as that of their male counterparts. Female soldiers may sometimes be ferocious fighters. But they almost always become propaganda figures as well. And in this dynamic, sex is never far from the surface — sometimes with horrifying consequences.

In modern military history, Nazi Germany was perhaps the force most committed both to bringing women into the military, and also to keeping their roles distinct from those of men. By the end of the Second World War, the total number of female Wehrmacht auxiliaries had risen to some 500,000, in roles such as signalling, operating Flak guns, or freeing up men for front-line service by performing clerical and back-office work. But Wehrmachthelferinnen were enjoined to serve without sacrificing their femininity, and never fought at the front.

By contrast, and in keeping with the Communist commitment to radical egalitarianism, the Soviet force that opposed them included many front-line female fighters. Of these, perhaps the most famous is the Ukrainian sniper Lyudmila Pavlichenko, also known as “Lady Death”. The most lethal female sniper in history, Pavlichenko notched up 309 confirmed kills, including 36 enemy snipers, before being retired after a shrapnel wound.

Popular profiles of Pavlichenko tend to treat her as a feminist trailblazer, albeit a dark one. Coverage of more modern Ukrainian female soldiers participating in the country’s defence against Putin has tended to come wreathed in a similar haze of you-go-girl liberal feminism, as have recent reports from Gaza that female IDF troops will now fight on the front line for the first time. Here, we find approving sentiments about the exigencies of war “upending” sexist “preconceptions about women in combat” and celebrating the denunciation of an “ultraconservative rabbi” who said Israeli female soldiers were “not Jews”.

We can infer that in America-aligned conflicts, winning means defeating not just the enemy, but also sexism everywhere. But a closer look at women in war throughout history complicates this picture, revealing a danger-zone for women warriors between two very different kinds of battle. And in this sense, at least in Herodotus’s account, the Amazons are perhaps the least ambivalent case in point. As he tells it, the Amazon rapprochement with the local Scythian men seems to have been broadly consensual, after the initial outbreak of fighting. Even so, the word Herodotus uses to describe the coming-together of the Amazons and their Scythian suitors — ἐϰτιλώσαντο — raises modern feminist scholarly hackles because some read it as meaning “had sex with” but also “tamed”. There is a connotation not just of sexual intimacy, but also of defeat, and masculine dominance.

This slippage between sexual intimacy and war, between “conquest” and conquest, disturbs modern sensibilities profoundly. But it pervades the literature of love, from Herodotus and Ovid through Les Liaisons Dangereuses and The White Stripes. A woman may be temporarily presented as a military figure — but the moment she is perceived as sexually available, military war is over, and another kind of conquest is sought. And the most famous warrior woman of the Middle Ages, Joan of Arc (1412-1431), saw this dynamic as such a grave threat to her effectiveness as a military leader that she fought almost as fiercely to defend herself against accusations of having surrendered sexually, as she did against the risk of surrendering militarily. Even after her capture, she enjoined the English to have a woman examine her for proof of virginity. And perhaps no wonder — even more than a century later, Shakespeare’s Henry VI plays set out to smear her posthumously by depicting her as a “trull” (whore) and suggesting she tried to escape death by pretending to be pregnant.

This in turn reveals a second, interconnected role played by women in war: as propaganda figureheads. Though commonly depicted in armour, Joan was never directly involved in fighting. Rather, she served as strategist and — importantly — as a rallying-point and morale-booster for scattered and battle-worn French forces who had been fighting on and off for decades by the time she appeared. In other words, Joan’s core role was less as a soldier than a symbolic figurehead — and to this end, within the moral framework of her era, the question of whether or not she remained “unconquered” was of immense significance.

Though the modern world is less fixated with virginity than Joan’s, more contemporary front line female soldiers also find themselves routinely confronted with questions about sexiness. On Pavlichenko’s 1942 US tour, despite her evident dedication to combat and lack of interest in being flirty, American journalists often seemed more interested in her femininity than her military achievements. She gave them short shrift, retorting to a question about makeup: “Who had time to think of her shiny nose when there is a battle going on?” And when one said that the cut of her uniform made her look fat, she replied that she wished he could experience a bombing raid, as “you would immediately forget about the cut of your outfit”.

But, deadly though Pavlichenko was, it appeared — like Joan — that her real power still lay less as a sharp-shooter than as a symbol. Batting away crass remarks about her looks, she addressed vast crowds, had a song written about her by Woody Guthrie, and helped to draw America deeper into the war. And while the modern-day Ukrainian sniper, “Lady Death”, Evgeniya Emerald, didn’t face the same salacious speculations about her sexual availability as either Joan or Pavlichenko, she nonetheless retired from combat after falling in love with a Ukrainian soldier and becoming pregnant in 2022. Even so, she has continued to serve as a propaganda figure: one who commands more than 100,000 followers on Instagram, where her more recent timeline has blended pregnancy and baby shots with fundraisers for the Ukrainian war effort.

As for the Amazons, for all that they seem to have relented of their own accord, Herodotus’s story suggests that whether men and women clash or cooperate on the literal battlefield, it’s not so easy to uncouple metaphorical conquest from the physical kind. Even Hitler’s Wehrmachthelferinnen were disparagingly referred to as “Offiziersmatratzen”, or “officers’ mattresses”, a reference to their supposed sexual availability.

Such encounters gesture in turn at the other, far less consensual aspect of this link between conquest and conquest: sexual violence. However much we fly the flag for gender parity, historically, the role women have played in warfare is not just as warriors, propagandists, or some mix of the two. The other point where sex and war collide is in “conquest” not of the metaphorical, romantic kind but the brutal, violent, and violating sort.

No doubt there were Wehrmachtshelferinnen among those German women who, after the war ended, bore the brunt of the notorious mass rape of German women by Pavlichenko’s one-time fellow soldiers. “The Russian soldiers were raping every German female from eight to 80,” reported the Soviet war correspondent Natalya Gesse. “It was an army of rapists.” In this, though, the Soviet army was hardly alone. Wherever the most violent and bloodthirsty human instincts are unleashed in war, rape re-emerges as a weapon. Against this, we might wonder what we’re really asking of those women now being lionised as you-go-girl avatars for “gender equality” amid the fog of war.

But perhaps, from the perspective of military propaganda, it doesn’t matter either way. If, for example, the service of Israeli women on the frontlines makes inspiring and sympathetic content for a Western readership, so too does their suffering if events turn against them. When such women are captured, and — inevitably — brutalised, their empty eyes and bloodstained faces also make for powerful propaganda.

Behind the cultural power of sex and war, then, lurk two dark, enduring facts. Firstly, that most men can kill most women with their bare hands, while the reverse is not true; and secondly, that most men prefer — consensually or otherwise — the other kind of conquest. Accordingly, throughout history, warrior women have played an ambivalent role in conflict: sort of fighting, but also sort of sex objects, and — in the confusing but powerful emotions this combination evokes — almost invariably vectors for propaganda.

I doubt there is any changing this. Whatever the blank-slatists may believe, there is likely no curing humankind of intermittent outbreaks of bloodthirstiness. And I doubt there’s much we can do either to eradicate the age-old patterns of human sexuality — even when their persistence obstructs the liberal feminist pursuit of absolute “gender equality” all the way to the battlefield. If this is so, women might ask themselves: is this kind of equality really something to fight for?

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com/