Australia imposed one of the harshest lockdowns in the world. While not as stringent as China’s, it was certainly among the longest and most severe measures for a Westernized democratic nation. In 2020, 2021, and 2022, I observed this unfolding in real-time on Twitter. What always baffled me was the distinct level of public support that the restrictions garnered in Australia.

While in the US, and to some extent, the UK, there was broad debate about what measures were excessively severe and what proved effective. The unique nature of the United States—a federation of states governing their own affairs in the majority of practical policies—presented opportunities for natural policy experiments.

A new study in the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Pediatrics, analyzes just how much increased harm was caused to children in Australia thanks to their pandemic restrictions.

A year before the publication of this study, I conducted an analysis of hospital records from the State of Rhode Island, utilizing data provided by my friend, Dr. Andrew Bostom. We discovered that we sent four times more children to the hospital for self-harm than for Covid.

Below are the key findings of the study.

COVID-19 and Pediatric Mental Health Hospitalizations

Jahidur Rahman Khan, Nan Hu, Ping-I Lin, Valsamma Eapen, Natasha Nassar, James John, Jackie Curtis, Maugan Rimmer, Fenton O’Leary, Barb Vernon, Raghu Lingam; COVID-19 and Pediatric Mental Health Hospitalizations. Pediatrics May 2023; 151 (5): e2022058948. 10.1542/peds.2022-058948

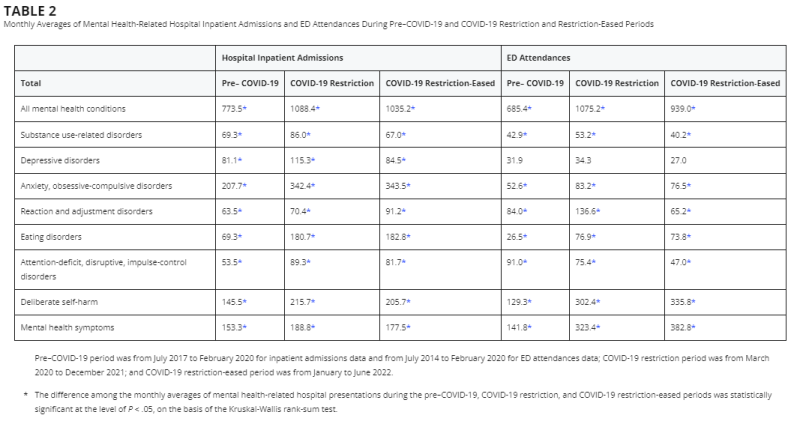

There were, on average, 1,088.4 and 1,035.2 mental health admissions per month during the COVID-19 restriction and the restriction-eased period, respectively, which was significantly higher (P < .05) than 773.5 admissions per month in the pre–COVID-19 period (Table 2). Regarding all mental health-related ED attendances, there were, on average, 1,075.2 and 939.0 attendances by month during the COVID-19 restriction and the restriction-eased period, respectively, which was significantly higher (P < .05) than 685.4 ED attendances per month in the pre–COVID-19 period. There was significant increase in the monthly averages of hospital presentations during the COVID-19 period than the pre–COVID-19 period for almost all different mental health conditions.

We found ED attendances for eating disorders had one of the highest increases over the COVID-19 restriction period among girls and those from the least socioeconomically disadvantaged areas.

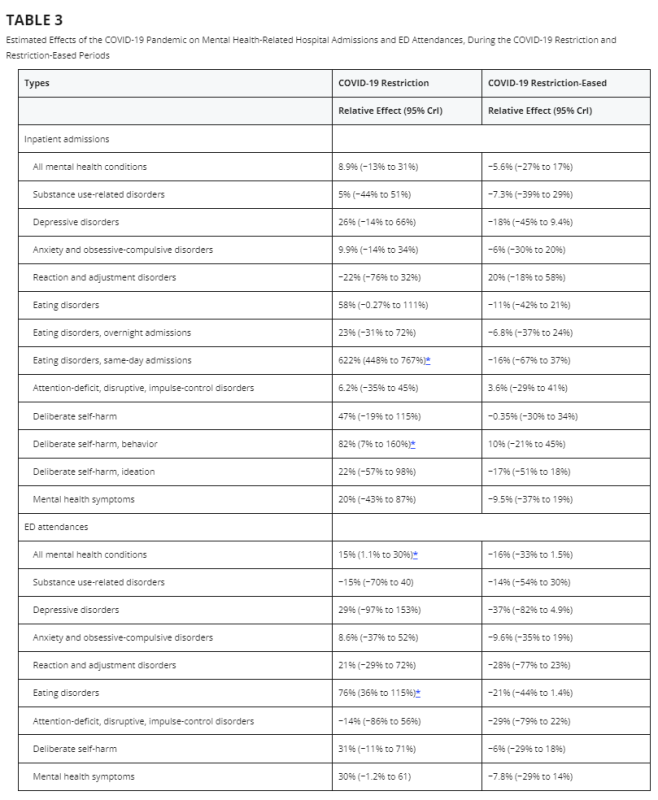

There was…. a 622% increase for same-day admissions for eating disorders during the COVID-19 restriction period.

During the COVID-19 restriction period, we also found an increasing difference in the monthly averages of mental health-related hospital presentations between females and males, compared with pre–COVID-19 period (2.64-fold and 2.35-fold increased difference for all mental health-related admissions and ED attendances, respectively). This difference was generally more noticeable for eating disorders, mental health symptoms, DSH, and substance use disorders.

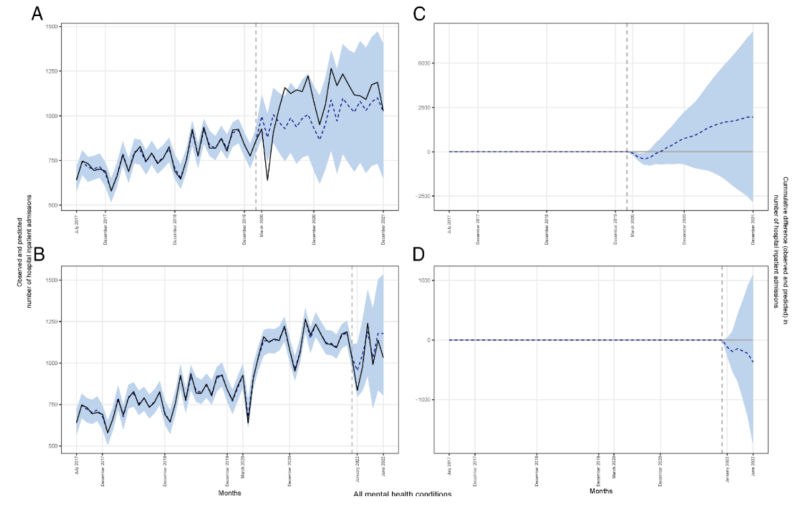

Monthly observed (solid line) and forecasted (dashed line) numbers of all mental health-related hospital admissions during the pre–COVID-19 and the COVID-19 periods in Australia (panels A and B); cumulative differences between forecasted and observed numbers of admissions in the COVID-19 period (panels C and D).

Monthly Averages of Mental Health-Related Hospital Inpatient Admissions and ED Attendances During Pre–COVID-19 and COVID-19 Restriction and Restriction-Eased Periods

Estimated Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health-Related Hospital Admissions and ED Attendances, During the COVID-19 Restriction and Restriction-Eased Periods

An intriguing aspect to consider about this study is what it doesn’t address. There’s a complete absence of any discussion about how many pediatric hospitalizations due to Covid were prevented. To remain objective, one would assume that considering the “benefits” of these restrictions upon children, beyond the acute mental health toll, would be necessary when evaluating the other side of this issue.

I’m speculating here, but I suspect this omission was intentional. If the cost/benefit was genuinely evaluated and measured, it would have been glaringly obvious that there was essentially zero benefit from an epidemiological standpoint.

While I am glad to see academic research finally publishing on this issue, it does not provide any sort of resolution to me. During the pandemic I was contacted by many a desperate parent who was looking for any kind of data and research to go and advocate for their kids. As a parent, I empathized deeply with these parents, and hope we never conduct this kind of mass experiment again.

Republished from the author’s Substack

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: Brownstone Institute Read the original article here: https://brownstone.org/