The media misremembers the Watergate scandal of 50 years ago in two significant respects: the first for an understandable reason, although one that ultimately is unflattering to the media. But the second misrepresentation defies explanation. Let’s take the puzzling one first.

The dominant narrative in the press is that Republicans, or at least a significant cohort of them, were participants in the Senate Watergate Committee’s search for the truth in 1973 and not strictly partisan or obstructionist. This narrative, of course, has enjoyed renewed popularity because of the obvious comparisons between Watergate and the serial high crimes and misdemeanours committed by President Donald Trump.

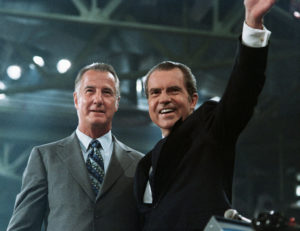

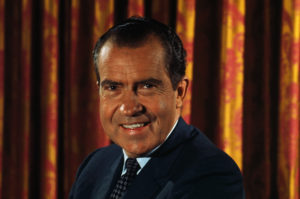

One question, uttered on June 28, 1973, supposedly exemplified Republicans’ bipartisanship. “What did the President know and when did he know it?” Tennessee Senator Howard Baker famously asked John Dean, President Nixon’s former White House counsel, who was now fessing up to his role as desk officer for the Watergate cover-up. For some reason, the context of Baker’s very first question to Dean has been forgotten. The ambitious senator was not engaged in a bipartisan search for the truth; rather, Baker was creating a firebreak that he hoped would protect Nixon’s presidency against what he realised had been three-and-a-half days of extremely damaging testimony. But there was one very large hole in Dean’s cool and detailed account. His first direct meeting of any consequence with the President had not occurred until February 27, 1973, more than eight months after the June 17th break-in. So while Dean believed he was carrying out the President’s wishes, he could not actually offer direct testimony about what Nixon knew and did in the earliest and most crucial phase of the cover-up.

Baker’s gambit gave every evidence of working — for two weeks. Then, in mid July, White House assistant Alexander Butterfield revealed the existence of an extensive, voice-activated tape recording system that promised to resolve what appeared to be an insuperable obstacle: who was telling the truth? As the late Stanley Kutler, the dean of Watergate historians, wrote, “discovery of the tapes undid Baker’s careful handiwork. The tapes made irrelevant his question to John Dean… [Because now] Richard Nixon himself could answer Baker, and in indelible words.”

Kutler’s observation was an understatement. Baker’s question had transmogrified into a battering ram against Nixon, until he was ultimately forced to give up the tapes, and it was his own words, more than any other single factor, that forced him into a humiliating resignation.

And what Baker did after his strategy backfired should not be forgotten either. He did not give up on his aim of being seen inside the GOP as the senator who saved Nixon’s presidency, a reputation that he hoped would put him head and shoulders above his party rivals for a future presidential run. While the president fought his way through the courts for months, hoping to avoid having to turn the tapes over to the special Watergate prosecutor, Baker and the minority counsel, Fred Thompson (a future Tennessee senator), desperately attempted a rearguard action. They sought to implicate the Central Intelligence Agency in the break-in, rather than the White House and Committee to Re-Elect the President. It was one of the most cynical acts in a scandal brimming with them.

About two weeks before the Senate Watergate Committee released its final report, in mid-July 1974, Baker and Thompson leaked their findings of alleged CIA complicity to the press. They landed with a thud, and were completely forgotten once the president released on August 5 what instantly became known as “the smoking gun” tape: an Oval Office conversation between Nixon and his top aide Bob Haldeman discussing how to use the CIA to impede the FBI’s Watergate investigation. Baker finally had the answer to his question.

Baker’s reputation suffered no lasting damage, in or out of the GOP. When his devastating question was remembered, as it often was, it was taken out of its intended context. And Baker exhibited no abiding impulse to correct the misunderstanding after Nixon’s disgrace was complete. Indeed, as time went on he absolutely welcomed the erroneous interpretation.

If rose-colored glasses and wishful thinking drive the false narrative about Watergate bipartisanship, the same cannot be said for the driving force behind the other misleading narrative. Here, vested interests, reputations, and a lot of money are at stake.

Philip L. Graham, the publisher of The Washington Post before Katherine Graham of Watergate-era fame, is frequently credited (albeit erroneously) with coining the saying that “journalism is the first rough draft of history.” That phrase is the problem in a nutshell. Those who wrote the first rough draft of Watergate have persisted in doing everything to ensure the first draft is also the final draft, aided enormously by the press writ large, eager to bask in the reflected glory.

The ubiquitous narrative about Watergate is still largely the one laid out in All the President’s Men, the 1974 book by Washington Post reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, which became an eponymous Hollywood blockbuster starring Robert Redford in 1976. As the literary critic Wilfrid Sheed noted, Americans might be getting fuzzy about the details of Watergate, “but at least they remember the movie: a couple of nosy journalists and an informer, wasn’t it?”

No one much noticed the degree to which the book was a product of, and influenced by, a passing fancy at the time, the so-called “New Journalism.” Books in this genre employed literary devices normally considered the domain of novels and put them to work in books that purported to be nonfiction. “Woodstein” exploited their factual authority as journalists while simultaneously enjoying the license granted novelists. The result was a gripping newspaper procedural focused most intensely on the first eight months or so of the scandal — but one that was a very narrow slice of that history and bore only a faint resemblance to what had actually gone on inside the confines of The Washington Post.

Most notably, All The President’s Men neatly sidestepped the truth that a troika — not a duo — was responsible for the Post’s coverage. Barry Sussman, a city editor who became the special Watergate editor in mid-July 1972, had been indispensable in producing the stories that won the Post a Pulitzer Prize. Indeed, managing editor Howard Simons believed that if any one individual, rather than the paper as a whole, deserved a Pulitzer, it was Sussman, not Woodstein. As Simons told Alan Pakula, director of the feature film, “Barry made acceptable the work of two junior reporters . . . [who] didn’t understand what they had often and couldn’t write it.”

Other principal actors slighted, if not maligned, in Bernstein and Woodward’s fabulistic account were the three federal attorneys assigned to prosecute the Watergate burglars; a slew of FBI agents doing the investigating; and the grand jury empaneled to hear the evidence, issue subpoenaes, and draw up indictments. The Watergate cover-up was not broken by the press, but by the legal pincers these actors built, which inexorably closed in on those who had committed perjury during the January 1973 trial of the burglars or otherwise conspired to obstruct justice. No one has ever conveyed a more balanced account of the press vs. the government’s role than Sandy Smith, a legendary reporter for Time magazine who broke as many important stories about Watergate as anyone in the Washington press corps, including Woodstein. After Nixon’s August 1974 resignation, Smith observed,

There’s a myth that the press did all this, uncovered all the crimes . . . It’s bunk. The press didn’t do it. People forget that the government was investigating all the time. In my material there was less than 2 percent that was truly original investigation. There was an investigation being carried out here. It may have been blocked, bent, botched, or whatever [at times], but it was proceeding. The government investigators found the stuff and gave us something to expose.

Finally, there is one last aspect that tells us more about the false narrative presented in All the President’s Men than any other element in the book. It involves the shadowy figure who became as inseparable from the book as the authors themselves, i.e., Sheed’s informer, aka “Deep Throat,” aka W. Mark Felt, the number two executive at the FBI when the Watergate break-in occurred. From 1974 to 2005, Bernstein and Woodward, wined, dined, and gave lectures for which they were handsomely paid, telling and re-telling stories of their reportorial prowess, with their cultivation of Deep Throat the apex of their Watergate reportage. Both journalists were hailed constantly for their supposed fidelity to their über-secret source. You could remove their fingernails and they still wouldn’t reveal Deep Throat’s identity.

It was actually a phoney mystery. A wizened, razor-sharp retired newspaper editor named Frank Waldrop, who was said to be “absolutely wired [in] to the FBI”, told the Washingtonian magazine, when asked about the Deep Throat guessing game in the spring of 1974, “Read the February 28 [1973] and March 13 [1973] Nixon presidential transcripts and then try someone like Mark Felt on for size.”

Nonetheless, that Woodstein held fast to their pledge of confidentiality to Deep Throat was widely accepted at face value. And it was true that they had, more or less, abided by all the “deep background” stipulations Felt laid down when he agreed to be a source for newspaper stories. But it was also true that Bernstein and Woodward had glaringly violated these same stipulations when writing their book. The public became aware of Felt’s existence as a source; his instrumentality in the stories; what he told Woodward and when. His words were supposedly quoted verbatim, and information he supplied Woodward was linked to specific Post stories, even exact passages. The only fig leaves left for Felt to hide behind was his risqué code name, after a pornographic film popular at the time, and the fact that he was identified as having worked at an unnamed “executive branch” agency.

Eventually the guessing game grew so popular, but wearying and tedious for the authors, that in 1976, Woodward developed a gambit that relieved the pressure while doing nothing to lessen public interest. Now celebrities in their own right, the duo declared that someday, they were fairly certain, history’s most famous whistleblower would come out of the shadows, claim his just reward by writing a fascinating book, and receive the acclaim that was his due. But until then, they were going to keep their word — unless Deep Throat were to die before publishing his story. No one imagined this was an entirely unilateral decision, just as the decision to include him in the book had been. Felt was already furious over the book’s serial violations of the “deep background” arrangement. He was not asked, and certainly did not agree, to be identified in the event of his death. Yet Woodward and Bernstein acted if this were a signed agreement stowed away in a safe-deposit box.

The dénouement finally occurred in May 2005, when Felt’s family and his lawyer outed him in the pages of Vanity Fair, hoping to cash in on the untold story. Bernstein and Woodward grudgingly admitted that Felt was Deep Throat, and the identification finally allowed for careful analysis about what Felt’s design had been all along — or what the late Christopher Hitchens said “rank[ed] as the single most successful use of the news media by an anonymous unelected official with an agenda of his own.”

Woodstein had long fostered, of course, their preferred interpretation of Felt’s motive: Deep Throat was a selfless, high-ranking official intent on trying to protect the office of the presidency from a criminal in the person of Richard Nixon. Felt “was trying to protect the office [of the presidency],” they wrote in 1974, “to effect a change in its conduct before all was lost.” Actor Hal Holbrook’s brooding portrayal of Deep Throat in the film version had then turned Woodstein’s portrait into something indelible.

But then a curious thing happened. In his own 2005 book about Felt, The Secret Man, Woodward backed away from Felt-as-principled whistleblower, and offered a far more pedestrian — and bureaucratic — explanation familiar to anyone who has laboured in the federal government. Felt leaked because he “believed he was protecting the [FBI]” from a corrupt, lawless president. Eventually Woodward reluctantly threw a third element into his admixture of motives: Felt was “disappointed that he did not get the directorship” following the untimely death of J. Edgar Hoover, who had died seven weeks before the break-in.

The sale of Woodward and Bernstein’s Watergate papers to the Ransom Center in Austin, Texas for $5 million in 2003, however, along with the release of the FBI’s Watergate files, opened the door to an independent assessment. When Woodward’s raw notes from his conversations with Felt were finally opened, none of the above explanations made sense. But a new one did: that Felt’s actions were entirely and only consistent with the “war of the FBI succession,” a no-holds-barred, vicious, internal struggle to succeed Hoover that had been going on for years. Felt leaked not out of pique or bitterness, not to protect the FBI, and not out of any concern over the office of the presidency. His sole aim was to destroy Nixon’s confidence in the acting FBI director, L. Patrick Gray, smear presumed rivals for the job, and steer Nixon toward appointing Felt himself. Richard Nixon was Felt’s only ticket to the directorship and the idea that Deep Throat ever intended to bring the president to ruin was absurd.

It defies belief that two of the most celebrated investigative reporters of their generation did not understand Felt’s true design contemporaneously, or, say, no later than 20 years after Nixon’s resignation. That Bernstein and Woodward still pretend otherwise tells one everything one needs to know about their first rough draft.

It was a fable, almost as self-serving as Felt’s leaks.

Disclaimer

Some of the posts we share are controversial and we do not necessarily agree with them in the whole extend. Sometimes we agree with the content or part of it but we do not agree with the narration or language. Nevertheless we find them somehow interesting, valuable and/or informative or we share them, because we strongly believe in freedom of speech, free press and journalism. We strongly encourage you to have a critical approach to all the content, do your own research and analysis to build your own opinion.

We would be glad to have your feedback.

Source: UnHerd Read the original article here: https://unherd.com